In 1969, at the “Golden Spike” centennial celebration of the First Transcontinental Railroad’s completion, the Chinese community nationwide had high hopes that the ceremony would provide an opportunity for the country to formally recognize the significant contributions of over 12,000 Chinese workers who helped build the one of the nation’s greatest engineering marvel.

Instead, Philip Choy — the chairman of the Chinese Historical Society of America, slated to talk for five minutes during the ceremony to pay tribute to the Chinese railroad workers — was pushed off of the speakers list. The Historical Society held a separate dedicatory ceremony afterwards. The sidelining was especially egregious given the erasure of Chinese workers’ contributions throughout the rest of the event.

“Who else but Americans could drill 10 tunnels in mountains 30 feet deep in snow?” asked John Volpe, then-President Nixon’s secretary of transportation, in his keynote address. “Who else but Americans could have laid ten miles of track in 12 hours?”

It was actually thousands of Chinese railroad workers, along with eight Irish rail handlers, who completed that remarkable feat, a product of a bet that Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) Company made with the competing Union Pacific Railroad Company, whose record time for one day was 7.5 miles of track.

The spectacular amount of financing and labor required meant that the completion of the railroad was remarkable by many metrics. The completion of the “Iron Horse,” as it was known, became shrouded in the romanticized mythology and folklore of Western expansion.

Several figures have survived this history, one of whom is Leland Stanford — the railroad tycoon president of Central Pacific who would come to be remembered fondly, along with his wife Jane, as the University’s founding family. The names of several of the Irish rail handlers would also be passed down through time.

But, all of the thousands of Chinese workers would be together remembered simply as “John Chinaman.”

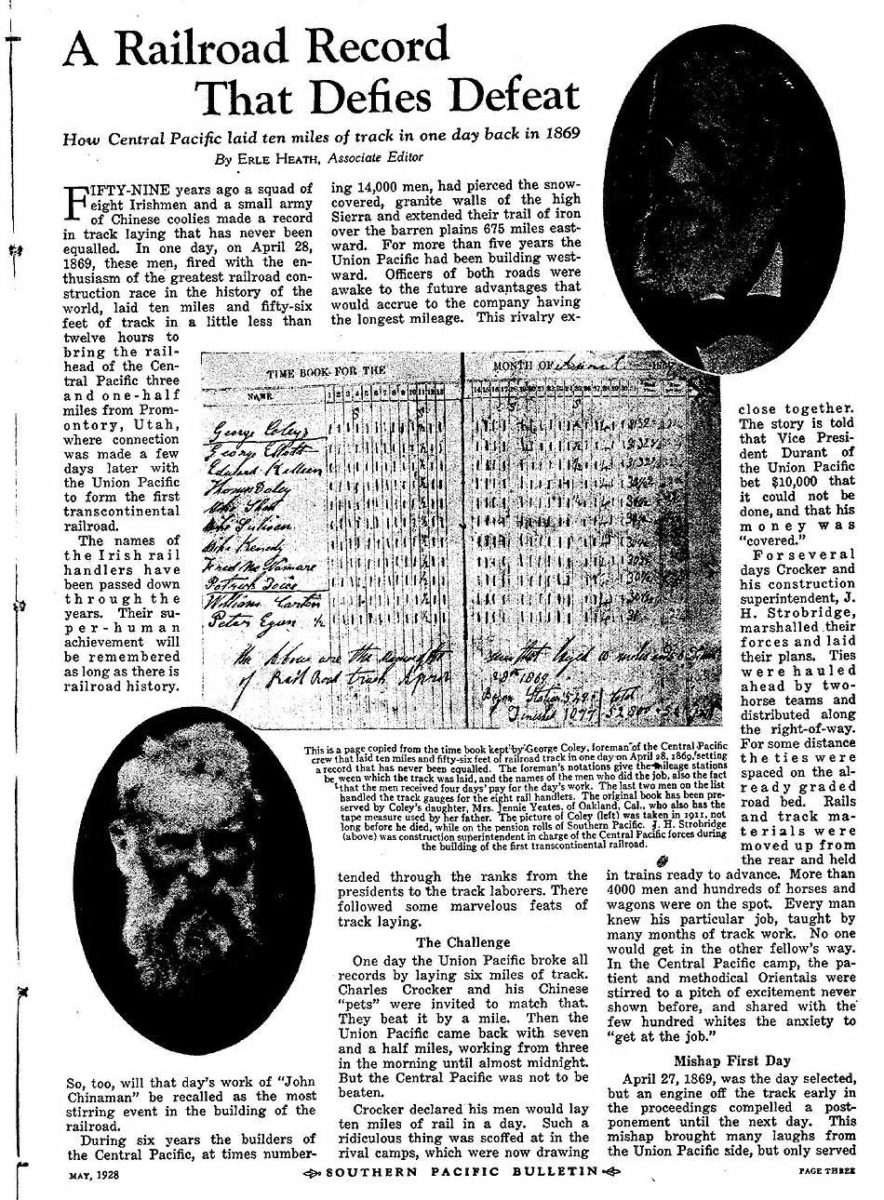

Article written by Erle Heath, associate editor of the Southern Pacific Bulletin, in May 1928.

In it, a time book kept by Central Pacific’s George Coley who was foreman for the crew that laid a record-setting ten miles of track in one day.

However, unlike in 1969, at this year’s Golden Spike ceremony — after a long 15 decades — the contributions of the Chinese workers were not overlooked.

This year’s celebration on May 10 came after significant scholarly effort to recover some of the missing history of Chinese railroad workers, much of which was done by Stanford’s own Chinese Railroad Workers Project (CRRW). Over the course of this years-long project, co-directors Shelley Fisher Fishkin and Gordon Chang attempted to piece together parts of the workers’ experiences and remember their legacy, even while honoring the mythology and lore that has traditionally surrounded the railroad.

“[The Chinese workers’ contributions were] front and center,” said Fishkin, an English professor. “Every single speaker acknowledged the contributions of Chinese railroad workers. No one acknowledged them in 1969.”

From pipe dream to global reception

So what changed over the last 50 years?

For one thing, the CRRW’s research was helped by the digital revolution, which has seen much material — including hundreds of 19th-century newspapers, documents and other records — scanned and digitized for use by scholars, who were then able to communicate with their peers electronically, oftentimes across countries.

“I searched through and downloaded thousands of digitized newspaper articles from the 1870s and 80s … and found, for example, that there were Chinese workers all over the country building railroads after Promontory as far east as Long Island and New Jersey,” Fishkin said. “But this is something that scholars of the previous generation could not do.”

The project also benefited from a “change in atmosphere,” Chang and Fishkin wrote in their book “The Chinese and the Iron Road.” They added, “interest in and support for efforts to recover the history of marginalized people have grown significantly.”

Chang, an American history professor, told The Daily that in the past, many accounts of the railroad did not mention the Chinese, or devoted little attention to them. The workers have been the recipient of historical inattention and marginalization, Chang said, largely due to authors who chose to glorify the railroad “barons” — which included Leland Stanford. This, coupled with the dearth of physical documentation available regarding Chinese laborers’ experiences, “explains why authors have failed to provide richer accounts.”

“Given historians’ reliance on the written document,” Chang and Fishkin wrote, “it is no wonder than the Chinese railroad workers have remained largely indistinct, a shadowy mass of figures hovering around the edges of our histories but never at the center of the story themselves.”

As a fourth-generation Californian with a lifelong curiosity about the workers, Chang was frustrated that their history was not consistently included in tales of the West and the U.S. in general. Fishkin had also been distressed ever since coming to Stanford by how little was known about the large group of Chinese workers who were hired by Central Pacific.

Frustration became opportunity in December 2011, when Chang received an email from Fishkin with the subject line “A pipe dream or brainstorm or maybe a really good idea.”

“I [had] realized that 2015 was coming up,” Fishkin recounted. 2015 would be the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the first group of Chinese workers who would go on to build the railroad.

“When I went to Special Collections to see whether they had a letter or a journal of one of these workers, they told me they had none,” Fishkin said.

So, Fishkin and Chang embarked on an ambitious research project, hoping to recover the history of the railroad workers in time for a conference on the sesquicentennial — or 150th anniversary — of the workers’ arrival.

“We thought we could finish it by 2015,” Fishkin said, laughing. “We had no idea how challenging it would be.”

The two scholars wrote to then-Provost and acting President of the University John Etchemendy describing their idea. Etchemendy gave them seed funding to launch the project.

“To his credit, Etchemendy recognized that this was a story that only Stanford could really tell — that Stanford had an obligation to tell.”

Shelley Fisher Fishkin

Fishkin and Chang conceptualized the project with the help of Dongfang Shao — the current chief librarian of the Asian Division of the Library of Congress, who was the director of Stanford’s East Asia Library at the time — and Evelyn Hu-Dehart, the Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Brown University.

Over the next couple of years, the project would bring together scholars and researchers from across Asia and North America in a series of conferences and workshops that laid the groundwork for a collaboration spanning many academic disciplines — archaeology, history, literature, American studies, ethnic studies and religious studies.

The project would also take many forms. The group would produce five books published in English and Chinese, most recently “The Chinese and the Iron Road.” They would also create traveling photography and history exhibits, an open-access digital repository hosted at Stanford Libraries and a curriculum guide produced in partnership with Stanford Program International and Cross-Cultural Education (SPICE) to make the research available to K-12 educators and students.

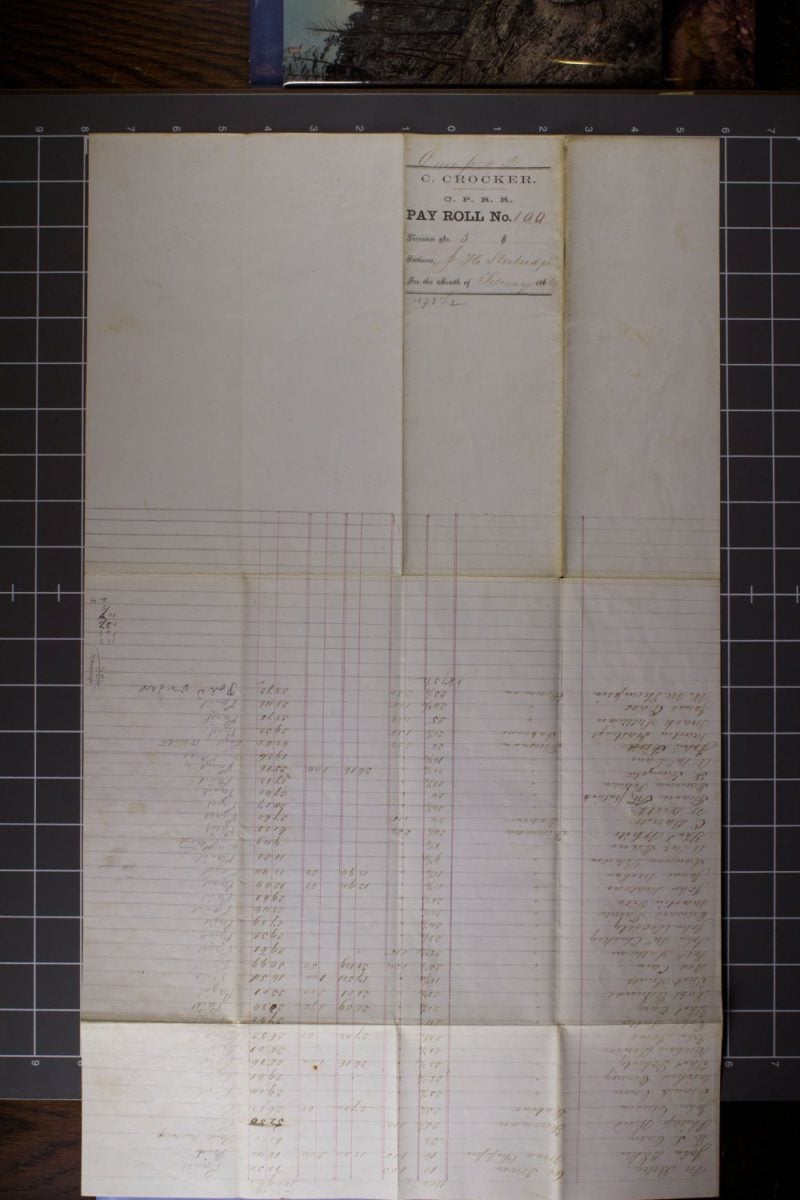

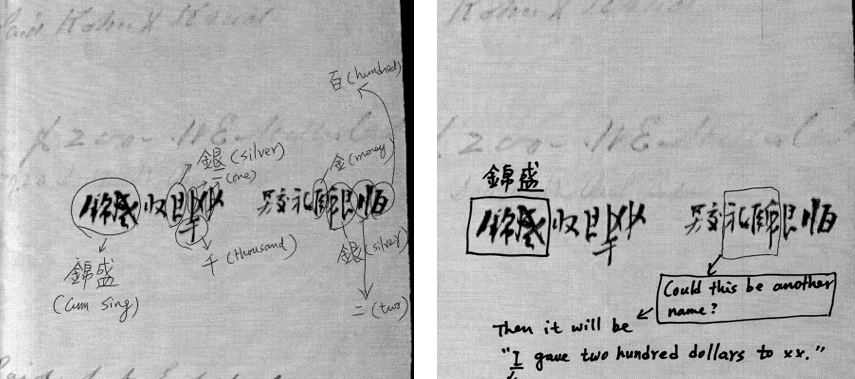

One of the payroll records for the Central Pacific.

Despite many successes and positive national and global reception, Fishkin said that there remains one aspect of the project that escapes them — they have yet to find textual evidence from any of the workers, such as a letter or journal, that could offer a glimpse into their experiences from their own perspective.

“We still haven’t found it, despite our conviction that one must exist,” Fishkin said.

Until then, historians, scholars and archaeologists are doing their best to piece together the workers’ experiences by organizing and deciphering records and archived documents, hunting down photographs, conducting interviews with the workers’ descendants and collecting and analyzing artifacts from work camps.

“They are really very imaginative,” Fishkin noted, referring to the collaborative and communicative process through which the project’s archaeologists have worked. “On the one hand, they’re very meticulous and concrete. But they’re also very good at figuring out what we can extrapolate from the material past.”

Details in the archaeology

This is not to say their work has not been fruitful — the team has collected everything from rice bowls to tools to payroll records, piecing the findings together using interviews with descendants of the workers.

Studying these peoples proved to be a daunting task, however. Project archaeologist and associate anthropology professor Barbara Voss ’88 described in a report the challenges of connecting the dots between archaeological artifacts — whose nature is to be anchored in a certain place — and the people who deposited them — in this case, the laborers who traversed thousands of miles to complete their job.

“Some of the larger work camps near major tunnels and bridges were occupied for several months or even a few years, but most were occupied for only a few weeks or days,” Voss said. “To understand the daily lives of the Chinese railroad workers, we had to find new research approaches that could account for this mobility.”

It took the effort of hundreds of Voss’ colleagues — “every archaeologist [she] could find who had ever studied a Chinese railroad work camp” — participating in conferences and workshops, sharing their findings and coordinating over email to bring together a vast body of data about hundreds of railroad camps.

Some uncovered details, like the dishes people used to eat their meals, revealed a great deal of uniformity across different camps.

“It became clear that often railroad workers had very little choice in the objects they used in their daily life, because supply chains to remote areas where they worked were controlled by labor contractors and the railroad companies,” Voss said.

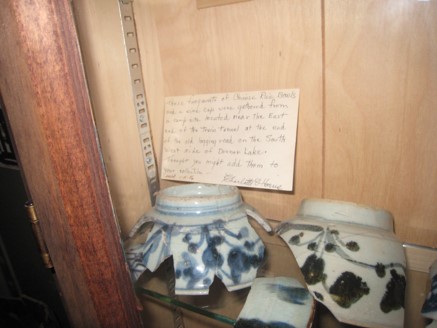

Courtesy of Barbara Voss.

Bamboo-pattern rice bowls found near a railroad tunnel camp site near Donner Lake. On display at Old Jail Museum, Truckee-Donner Historical Society.

At the same time, the researchers’ findings revealed local variation in the Chinese railroad workers’ experiences and gave insight into how they might have adapted to different circumstances. For instance, at the Bodie and Benton railroad camp (near Mono Mills in California), archaeologists found evidence that the workers traded porcelain dishes with local Native American Paiutes in exchange for pine nuts and other foodstuffs.

Along with rice bowls, archaeologists also found parts of cooking hearths and bone fragments indicating that the workers were buying and eating cattle from local cattle owners. They did, however, also insist on eating Chinese food — rice, dried vegetables and oysters, abalone fish and pork.

Archaeologists were also able to find homeopathic and patent medicine bottles that shed insight into how the Chinese cared for themselves when they fell ill, as well as recreational items like disk-shaped gaming pieces that workers had cut from used metal cans, carved bone dice and black and white glass disks.

Chinese work camps also had high frequencies of opium and alcohol paraphernalia, including bottles of alcohol and opium tins and pipes, according Voss’ report. These artifacts are usually interpreted as having been for recreational purposes, although evidence suggests that the substances may have often been used as remedies for work-related injuries, infections and the physical and psychological pains of the workers’ taxing manual labor.

When the archaeologists compared the prevalence of opium pipe remains in work camps versus in urban Chinatowns, they found heavier use of opium among railroad workers. Fishkin said that this difference could suggest that smoking opium offered relief from the workers’ injuries and pain.

Yet to understand Chinese railroad workers’ lives in a more meaningful way, Voss said the researchers had to move beyond North America to study the workers’ home communities in southern China. To do this, she worked with architectural historian and professor Jinhua Tan at Wuyi University in China to develop the first archaeological investigation of a Chinese railroad workers’ home village in Cangdong in Kaiping County, Guangdong.

According to Voss’ findings, villagers in Cangdong were consuming a significant amount of U.S- and European-manufactured foods, like earthenware pottery, medicines, grooming products and clothing. Therefore, “it’s likely that Chinese railroad workers were already familiar with these goods before they came to the United States,” which could have made the transition easier for them.

Studying the places the Chinese workers occupied both in the U.S. and in China was also crucial in understanding and getting to know them as more than just laborers, but as individuals. The project team believed that the workers came from all walks of life, and that many may have been educated professionals — not illiterate as they were often thought to be. Faced with political and social turmoil, many, particularly from southern China, fled to the U.S.

Fishkin recalled visiting the California State Railroad Museum and seeing a line of Chinese calligraphy: the signature of a worker, likely a contractor, named Cum Sing on a receipt for his payment.

The signature of a worker, named Cum Sing, on a receipt for payment he received. One of Fishkin’s colleagues in China said he could tell that, by the way the letters were written, the man had been trained as an accountant.

“Our colleague in China looked at that line of calligraphy and said he could tell from the way the letters and numbers were written that the man had been trained as an accountant,” Fishkin said. “It confirmed our sense that these were not all unlettered farmers.”

Complicating the railroad legacy

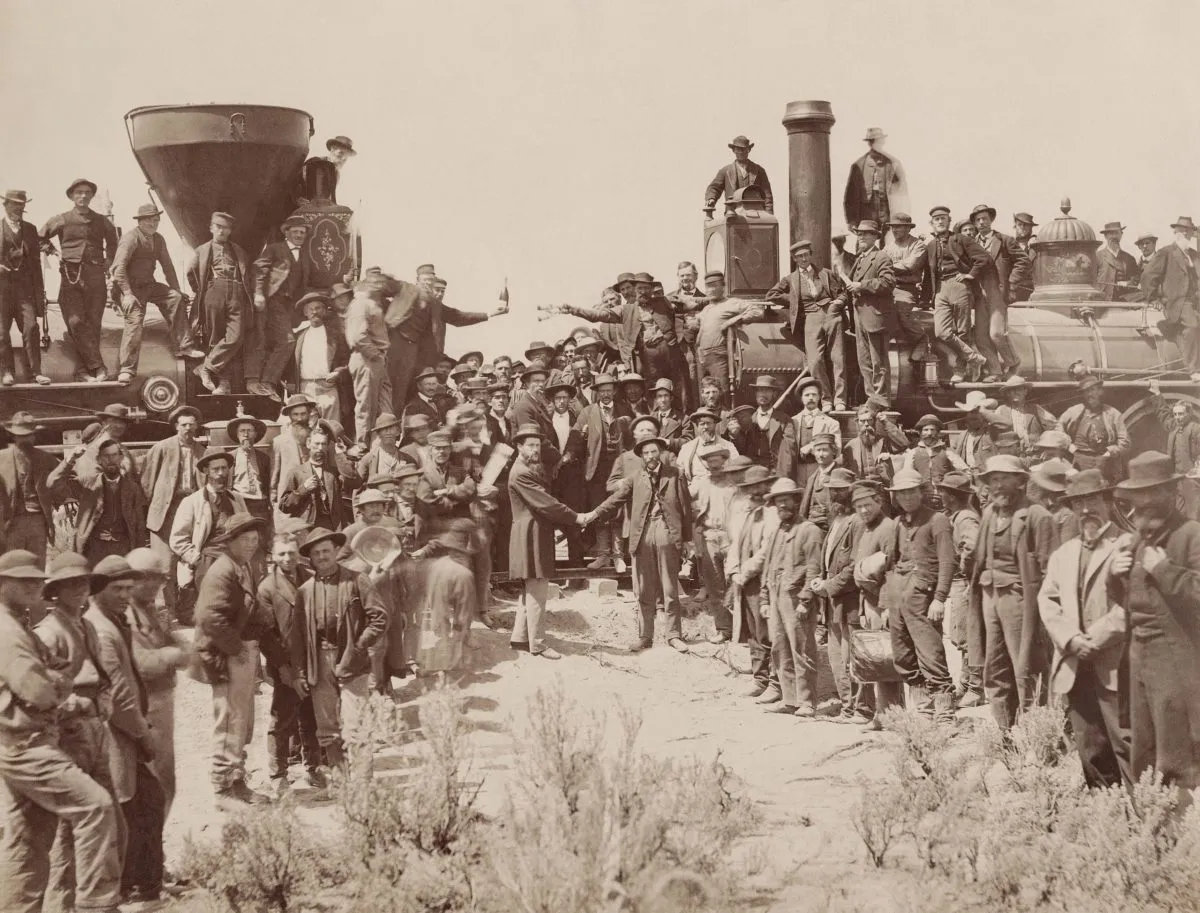

Almost exactly 150 years ago, Leland Stanford hammered in a ceremonial 17.6-karat gold spike at Promontory Summit, Utah — the last spike needed to join the Central Pacific and Union Pacific rails and completed the First Transcontinental Railroad.

A single word — “DONE” — was then transmitted via telegraph from coast to coast, setting off a wave of festivities across the nation.

When the Transcontinental Railroad was first authorized by Congress in 1862, the specific route was still undetermined. But it was decided that the Central Pacific section would build from Sacramento, California eastward while the Union Pacific section would build from Omaha, Nebraska westward. Promontory Summit was the point where the two rails would meet, physically and symbolically connecting the eastern United States with the West.

When the project was finally completed, a journey across the country that would once have taken six months by land or six weeks by sea now took only seven days by land and cost hundreds of dollars less. The continuous rail line served as a direct passage for the exchange of goods and people, reinvigorating the country’s economy.

“It was the point at which the country was unified,” Fishkin said. “So it was extremely important for America’s debut on the global stage as a modern nation — and the Chinese were central to making that happen.”

Photograph taken after the driving of the golden spike at Promontory, Utah, completing the nation’s First Transcontinental Railroad. No Chinese workers were pictured in the photograph.

The early mid-1800s were marked by the California gold and silver rush, and also saw a heavy influx of Chinese immigrants enraptured by the allure of gold and looking to escape economic distress, conflict and famine caused in part by a devastating civil war in southern China.

Many went to great lengths in making the trip to the U.S. Researchers found that one railroad worker, Jun Yuk Chow, traveled by river ferry from Kaiping county in Guangdong to Hong Kong, then booked a third-class passage on a three-mast sailboat across the ocean to San Francisco in a journey that would take 48 days.

After their arrival in the West — and despite their contributions to the Transcontinental Railroad — Chinese laborers would be faced with hostility and xenophobia, culminating in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act which prohibited their immigration for 10 years and banned them from becoming U.S. citizens.

Congress wouldn’t issue an apology for the law for another 129 years.

Anti-Chinese sentiment quickly became a talking point for Leland Stanford, who served as the first Republican Governor of California from 1862 to 1863. During his campaign and almost two-year governorship, Leland championed the 1892 Geary Act, which extended the Chinese Exclusion Act even further. He also vilified the Chinese beyond his policies, stating in his inaugural address to the state legislature that “the settlement among us of an inferior race is to be discouraged,” calling for the “repression of the immigration of the Asiatic races” and warning against what he called the “dregs” of Asia.

Yet it was these very “dregs” who generated Stanford’s enormous wealth in the first place. Chang, Fishkin and many others working on the Chinese Railroad Workers Project maintain that the success of the railroad depended largely on the contributions of Chinese workers — “without them, the Central Pacific Railroad would have failed,” Chang said.

It was a sentiment that Leland would end up acknowledging. In a letter to President Andrew Johnson in 1865, the robber baron wrote that it would have been “impossible to complete the western portion of this great national enterprise” without the Chinese workers.

“[Leland] Stanford came to realize that his economic survival, the survival of the railroad enterprise, depended on the Chinese,” Fishkin said.

Voss wrote that Leland and Jane Stanford would end up employing thousands of Chinese laborers in their other enterprises and to work on their vineyards, ranches and estates. Later, when Stanford was founded, the University admitted students of all races including Chinese immigrants and those of Chinese descent.

By most accounts, the Central Pacific employed Chinese laborers to do the work that white Americans didn’t want to do. Both Union Pacific and Central Pacific initially tried hiring white workers, predominantly Irish ones, but were unable to do so fully.

“When the [construction of the] Central Pacific began to approach the Sierra Nevada, the Euro-American workers began quitting, because the work was too hard and the pay too low, and they didn’t want to do it,” Fishkin explained.

For a job that needed 5,000 workers, the railroad received only 800 responses to an advertisement posted in post offices throughout California. Most white workers had instead chosen to return to agriculture or hoped to strike rich in gold and silver mines.

Faced with a labor shortage, the railroad began hiring Chinese workers already in the U.S. out of necessity, and later began recruiting them directly from China, mostly from Guangdong.

Unforgiving working conditions

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Chinese workers experienced unequal treatment while working for the railroad. They completed six or seven backbreaking days of work each week, laboring from dawn to dusk, and were paid $31 to $35 per month — 30 to 50 percent less than white workers, who were demanding at least $2 a day. They also had to provide their own food, tools and sometimes lodging, according to Fishkin.

“It’s estimated that they cost the railroad [only] two-thirds of what white workers cost,” Fishkin said.

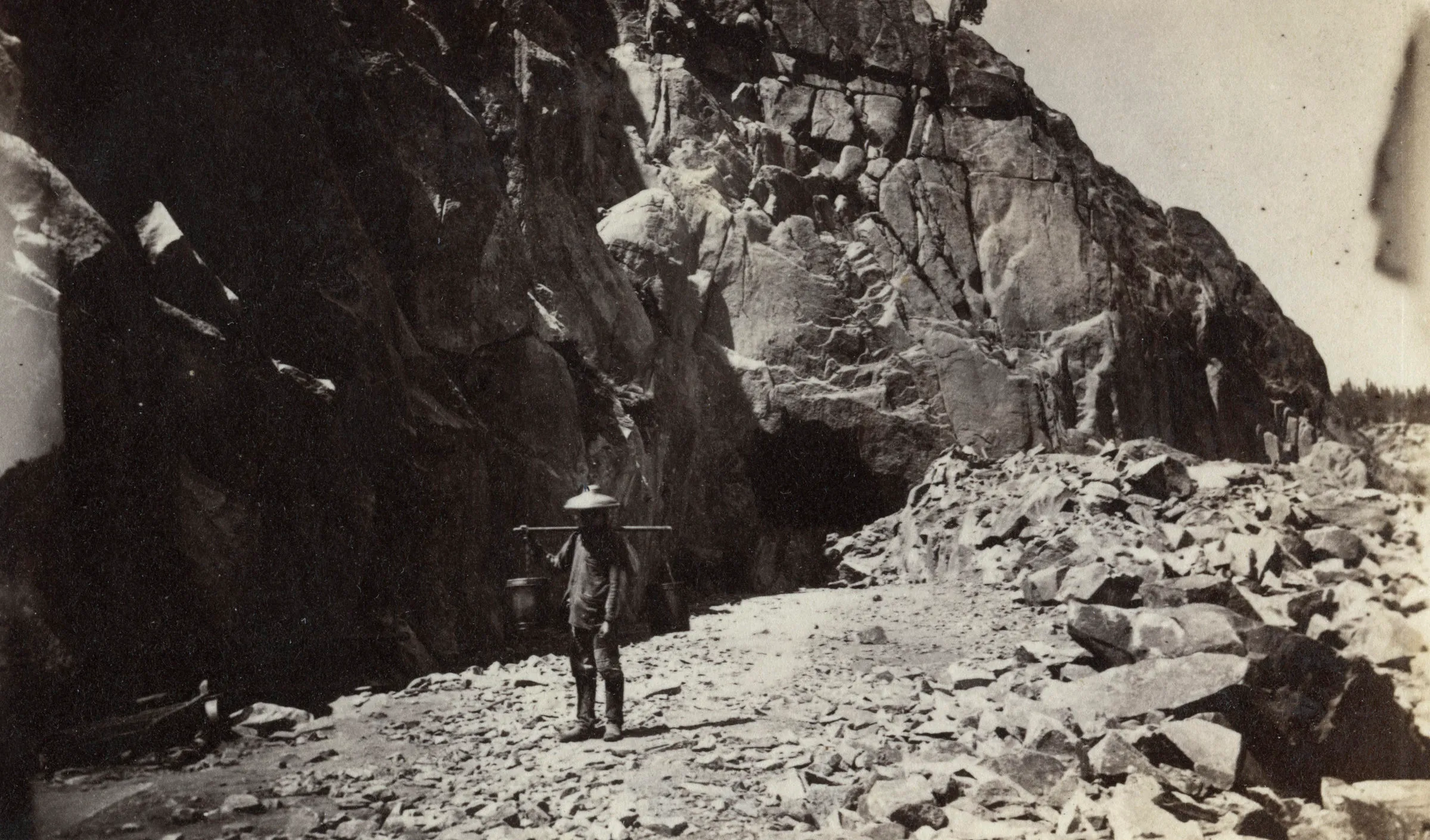

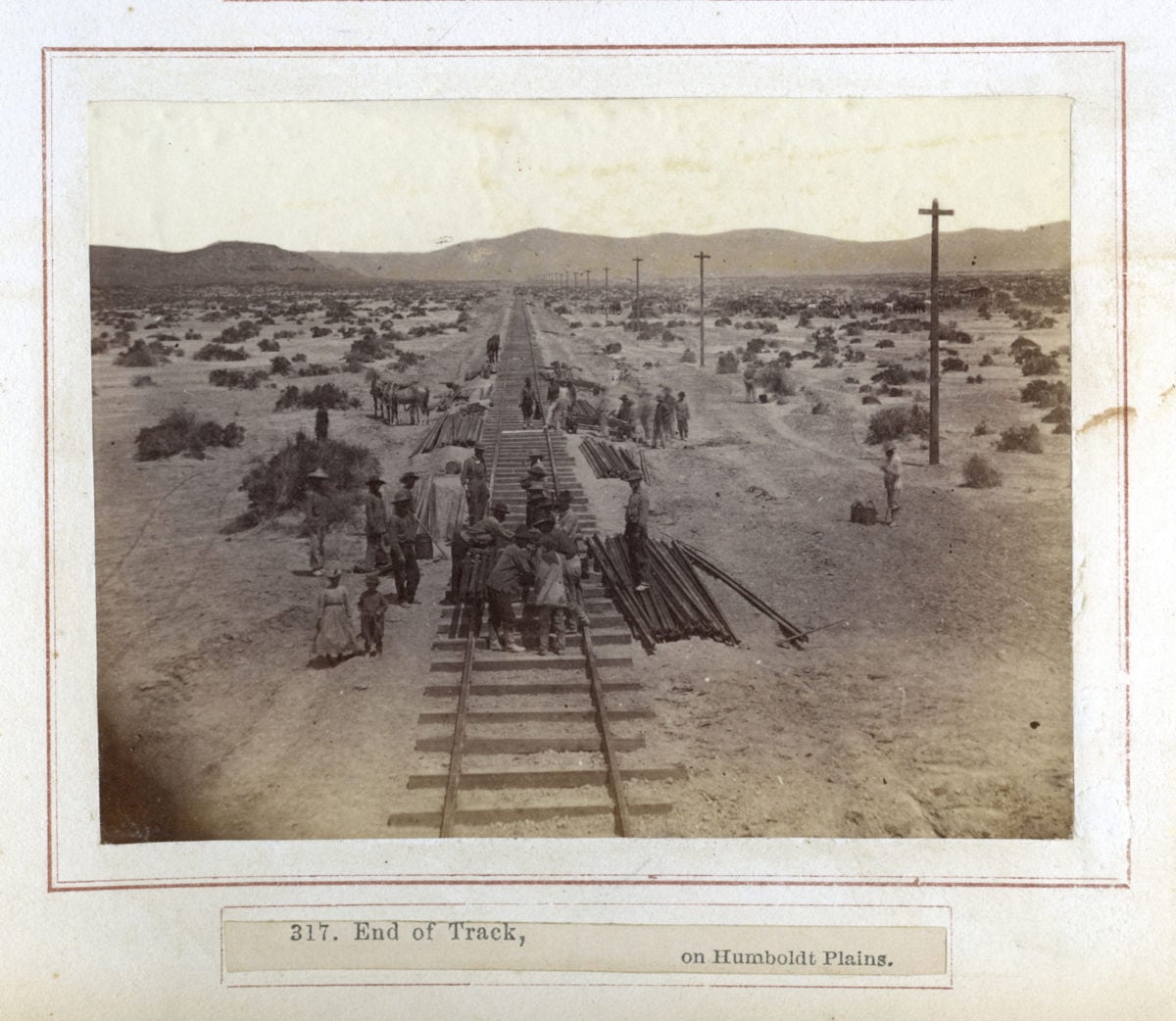

Chinese railroad laborers working on the Central Pacific Railroad near an opening of Summit Tunnel.

In April 2016, Chinese Railroad Workers Project scholars from Canada, China, Taiwan and the U.S. traveled to the Sierra Nevada mountains to explore tunnels — many of them cut from solid granite — that Chinese workers excavated.

The terrain was unforgiving, even in the spring. Fisher told The New York Times that the guide she and her colleagues had been traveling with slipped on a patch of black ice in a tunnel and broke their shoulder.

“If that’s what the tunnels were like in April, how treacherous [would they be] in the winter?” Fisher mused.

The work involved intense manual labor. At the time, the labor-saving devices available were mostly wheelbarrows, horse-pulled carts and a few railroad-pulled gondolas. Otherwise, workers used hand tools and their own muscles to blast through tunnels, build the railroad track bed and lay down tracks.

Shelley Fisher Fishkin

“We literally would not be sitting in these buildings — these buildings would not exist — without the work of these Chinese workers.”

The labor was undoubtedly dangerous. Chang said that great numbers died, perhaps over 1000 workers. Construction casualty records were not kept, so the specific number remains unknown, but historians estimate that one in 10 workers lost their life from explosion accidents, landslides, avalanches, heatstroke or hypothermia. Research also shows the callous way in which Chinese workers, whose individual names were not recorded by Central Pacific, were often treated.

“To avoid interrupting construction schedules, labor contractors and line supervisors maintained a pool of able-bodied men who could replace injured and dead workers at a moment’s notice,” Voss wrote.

Repaying the debt

The members of Chinese Railroad Workers Project view their efforts as payment for a debt owed to the Chinese workers, whose labor in large part helped build the fortune with which Leland Stanford would — two decades after the completion of the railroad — establish his namesake university. Because of this, Fishkin thinks of the workers as Stanford’s “first benefactors.”

“We literally would not be sitting in these buildings — these buildings would not exist — without the work of these Chinese workers,” she said.

Voss, who was an undergraduate student at Stanford before becoming a faculty member in 2001, described her education and livelihood as something “made possible [by] the wealth that was generated by Chinese railroad workers’ labor.”

“As a faculty member of the university that bears his name, I am painfully aware that Leland Stanford became one of the world’s richest men by using Chinese labor,” Chang wrote in a recent op-ed for the Los Angeles Times.

But the workers’ contributions didn’t end after the Promontory Point Golden Spike ceremony 150 years ago. Fishkin said that the Chinese continued to work at the University long after the railroad had been completed; one of the things that campus archaeologists found while researching for the project, she said, was that every palm tree lining Palm Drive was planted by a Chinese worker.

“I’m very grateful to them,” Fishkin said. “I felt that doing this research was a way of repaying the debt. Because we do owe them a great deal.”

This article was corrected to show that there was a gold and silver rush in the mid-1800s, not just in 1860. The Daily regrets this error.

Sean Lee contributed to this report.

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.