Following a yearlong legal battle in which a coalition of students accused Stanford’s leave of absence policies of discriminating against those with mental health disabilities, the University agreed in a settlement released Monday to treat mandatory leaves as a last resort and provide access to one quarter of on-campus housing for some students on leave.

“We’re very happy about being able to reach the terms that we did in the settlement,” said Caroline Zha ’20, co-director of the Mental Health & Wellness Coalition, which is a plaintiff in the suit.

A primary allegation in the suit, filed May 17, 2018, was that Stanford imposed a “blanket policy” of placing students who undergo a mental health crisis on mandatory leaves of absence, without considering all potential ways the University could keep them on campus. Students were forced to immediately withdraw from all classes and were stripped of their housing.

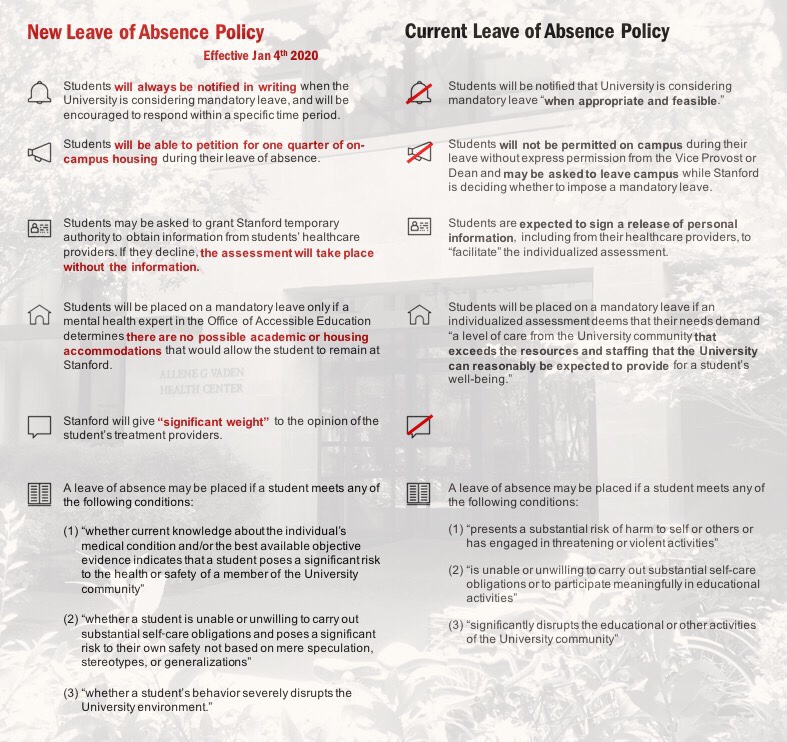

The new policy, which takes effect Jan. 4, 2020, requires that a mandatory leave only be pursued if a consultation with a representative from Stanford’s Office of Accessible Education (OAE) with expertise in mental health disabilities cannot find reasonable accommodations that would permit the student to remain at Stanford without taking a leave of absence. These accommodations may pertain to academics or housing.

“I won my lawsuit against Stanford,” plaintiff Harrison Fowler ’22 wrote in an Instagram post about the settlement. “I paid no money, I received no money. Leave of absence policies at Stanford have now changed for the better.”

Furthermore, students with mental health disabilities will be eligible to petition for one quarter of on-campus housing while they are on leave. Previously, Stanford extended this housing right to only students with non-mental health related medical disabilities and prohibited students on mental health-related leave from living on campus or participating in University-related activities.

“The key change from the old policy to the new is that it is now required to go through every possible reasonable accommodation before a leave is implemented, which will eliminate the need for leave in some cases, we anticipate,” said Monica Porter, the attorney representing the plaintiffs in the case.

Also among the suit’s complaints was Stanford’s disregard for the recommendation of students’ outside mental health providers against leaves of absence, which happened in the case of a plaintiff referred to as Rose A. Under the new policy, Stanford will give “substantial weight to the opinion of the students’ treatment providers” in its assessment of whether a student should be placed on leave, Porter said.

When a student is ready to return from leave, Stanford’s assessment of the student will be of whether they are able and ready to return to the University with or without reasonable accommodations — for example, by giving students the option to return part-time. Students returning from leaves of absence are also no longer required to submit personal statements justifying their readiness to return, a measure some plaintiffs felt required them to take the blame for something that was out of their control.

The settlement further stipulates that Stanford must provide clearer documentation on the OAE website on what accommodations are available to students — especially those with less visible disability such as mental health disability — since many are unaware of the accommodations they are entitled to under federal law. The accommodations now listed on the OAE include, but are not limited to, reduced course load, recording missed classes and changing dorm rooms.

“Above all, the most important impact we hope the policy changes will have on students is to encourage them to know their rights and ask for the accommodations that they are legally entitled to,” Zha said. “Experiencing a mental health crisis is scary and often traumatizing, and the institutional barriers and administrative hoops that you have to jump over and work through in the aftermath can be even moreso.”

The University will use the rest of fall quarter leading up the new policy’s winter quarter implementation to “develop clear processes, to engage and train all staff members who will interact with the new policy, and to provide an opportunity for information sessions during which interested community members can ask questions about the new policy and the processes it will prescribe,” according to a statement released by Vice Provost for Student Affairs Susie Brubaker-Cole.

“Of course, there is always additional work to be done, and we look forward to continuing to work with student activists and administrators to continue to strengthen and improve mental health resources and policies on campus moving forward, in order to ensure that all students feel safe and supported seeking help at Stanford,” Zha wrote in a statement to The Daily.

Contact Claire Wang at clwang32 ‘at’ stanford.edu.

This article has been updated with information from the University’s statement on the settlement. This article has also been updated with comment from plaintiffs in the case.