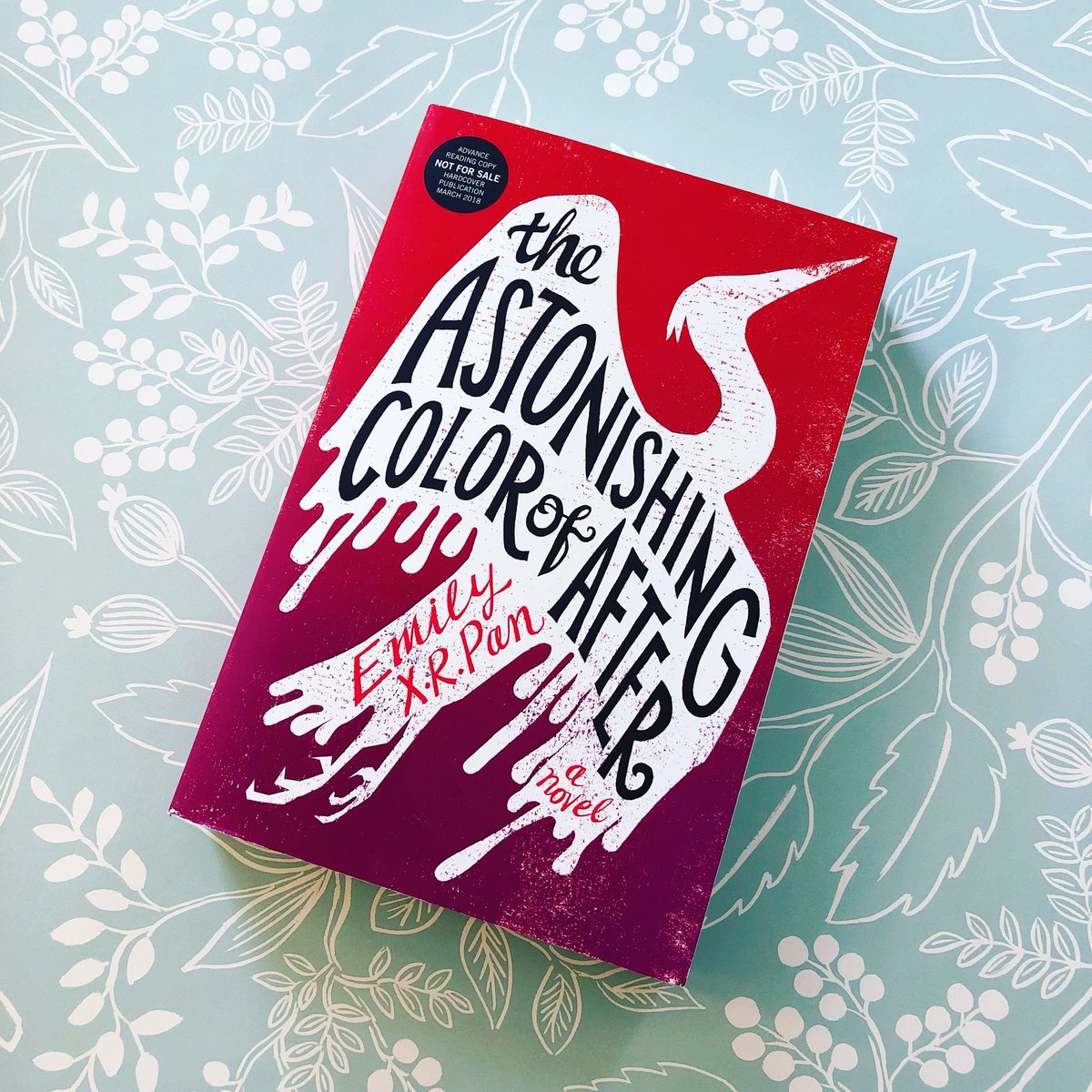

Emily X. R. Pan’s debut novel “The Astonishing Color of After” evocatively portrays the struggle to move past grief amid a coming-of-age journey to understand one’s cultural roots.

Leigh Chen Sanders, age fifteen, is biracial with Taiwanese and Irish-American heritage. She is a budding artist who is in love with her best friend, Axel Moreno, with whom she shares the habit of describing their feelings through color. Though her parents’ relationship is initially full of laughter and Sunday mornings with fresh waffles, with the frequent academic travels of her sinologist father and her mother’s spiraling depression, Leigh’s home becomes a somber, dark place. And as Leigh soon learns, what is fragile will often break: on the same day she kissed her best friend for the first time, her mother took her own life.

After the funeral, Leigh begins to see her mother as a bright vermillion bird who leaves her red feathers as clues and urges her to go to Taiwan. Leaving her relationship with Axel unresolved, during her summer break she visits her maternal grandparents overseas for the first time, determined to understand her mother’s crossed-out last words, “I want you to remember.”

The setting of Taiwan is caringly described, enriched by Leigh’s insistence to visit her mother’s favorite places and with the interpretation help of a woman named Feng, who is not all what she appears. Despite her unfamiliarity with the language, Leigh begins to reconnect with her grandparents and start mending the cracks that first separated them, metaphorically and literally weaving a net to help each other recover.

Told through a series of flashbacks prompted from burnt incense sticks and emails from her best friend, Leigh starts to unravel long-buried family secrets while wrestling with the weight of her mother’s illness and her father’s guilt, while wondering where it all went wrong. With her grasping for the right words to translate her volatile emotions and new discoveries, the story is an emotionally charged depiction of culture clash, loneliness and the difficulties of moving on after tragedy.

At 480 pages, the lengthy descriptions of feelings through color can drag the story, though the beauty of the figurative language does immerse you in the pleasure of reading. Likewise, the revelations and neatly-wrapped plot threads at the end of the book almost seem prematurely tied together, disproportionate to the first half that emphasized the “mother-shaped hole in me” and the magical elements — all related to her mother’s rebirth as a red bird — that tenderly fleshes out Leigh’s longing for her mother.

Nevertheless, the novel does many things well, capturing that curious feeling of being stranded between worlds while showing the arc of recovery after loss, as symbolized by Leigh’s final interaction with her mother’s red bird that soars towards the heavens and leaves her a handful of silky feathers to remember her by. And as Leigh sifts through her memories, she recalls her mother’s excellent advice, “Once you figure out what matters, you’ll figure out how to be brave.” Reading this novel also inspires one’s courage to flourish, to move on after a loss, to be brave.

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.