Last year, Stanford saw an unprecedented increase in campus voter turnout. StanfordVotes, a Haas Center initiative that seeks to register and mobilize voters, had registered over 2,500 people by November 2018. While less than 17% of eligible students cast their ballots in the 2014 midterms, that proportion shot up to 42.9% in 2018. Most significantly, the voter turnout rate among registered students more than doubled, from just over 30% in 2014 to just under 70% in last year’s midterms.

This heartening upsurge in political participation extended far beyond Stanford. The 2018 elections boasted the highest midterm turnout in four decades, with 53% of the citizen voting-age population turning up at the polls. The Census Bureau highlighted the turnout spike among 18-to-29 year olds and voters of color as core drivers of the increase. These statistics, as well as the inspiring change they represent, are certainly cause for celebration. An energized, engaged electorate ushered in the most diverse U.S. Congress in history—a promising harbinger of the reinvigorated, broadly representative American democracy that will, in my optimistic prediction, rise from the ashes of the Trump era.

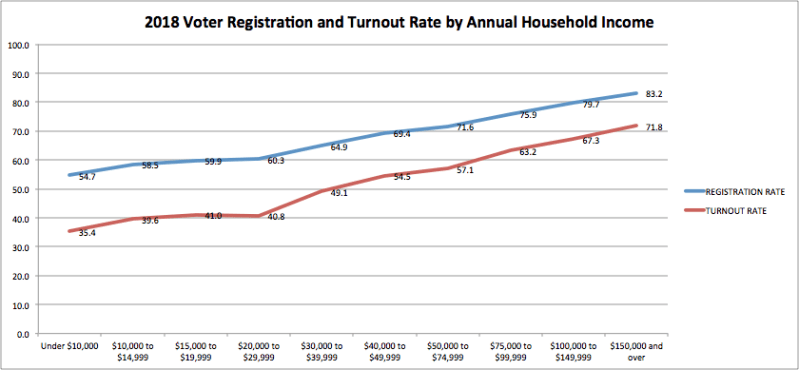

However, the Census Bureau’s summary of voter data does not convey the complete picture. Digging into some of the spreadsheets myself, I noticed one especially troubling trend: stark disparities in voter registration and turnout by household income bracket. In 2018, only 54.7% of Americans whose households made under $10,000 annually were registered to vote, as compared to 83.2% of Americans whose households made $150,000 and over. When it comes to voter turnout, the disparity is even worse—only 35.4% of Americans whose households made under $10,000 turned out to vote, as compared to 71.8% of Americans whose households made $150,000 and over. (See Table Seven on this page of downloadable census data.) Although American democracy promises an equal franchise to people of all class backgrounds, the richest Americans are twice as likely to vote as the poorest.

Anyone who believes that an equal right to vote is essential to our democracy ought to find these disparities disturbing. They point to a fundamental social injustice: increasing levels of economic inequality are eroding the promise of equal citizenship itself. Political theory can offer some insight into why this matters. In “A Theory of Justice,” a staple of late 20th century liberal egalitarianism, political philosopher John Rawls sets out two core principles. First, Rawls asserts a right to equal basic liberties, including the right to political participation, among all citizens. Second, although everyone is guaranteed their fundamental freedoms, Rawls grants a place for social and economic inequalities, but only under a few conditions: inequalities must make the least advantaged members of society better off, in absolute terms, and everyone must have an equal opportunity to pursue activities that could result in an unequal distribution. In addition, before introducing socioeconomic inequalities, the first principle of justice—equal basic liberties for all people—must be secured. In other words, economic and social inequalities are only permissible once fundamental freedoms, including political participation, are guaranteed for all.

That standard starkly contrasts with our status quo. In Rawls’ just society, some people would be richer than others, but wealth disparities would not translate into inequality of political voice, because socioeconomic inequalities are not permissible until equal access to the political process is guaranteed. No one would be able to leverage material resources to amplify their political influence or drown out the voices of others. Household income would certainly have no bearing on whether a person exercises the right to vote. By contrast, in America today, socioeconomic status is a powerful predictor of political participation, implying that poverty and inequality make it harder for some people to make use of their basic rights.

These might seem like abstract philosophical concerns, but they have real-world material consequences. Loss of political voice further entrenches the inequities that lead the poor to be excluded in the first place. Because poorer citizens are less likely to vote, politicians can sideline their interests without paying a steep political price. Politicians have greater incentive to pass policies that cater to the 70% of high-income Americans who vote, rather than the 65% of extremely low-income Americans who do not. This might explain why government policy has done little to meaningfully address the decoupling of wage and productivity growth, permitting income and wealth inequality to skyrocket.

Election turnout is not the only explanation for the disproportionate influence of wealthier citizens. Corporate interests are overrepresented in Washington; businesses account for 52% of organizations that lobby in D.C. and 77% of total spending on lobbying, while labor unions only account for 1% of each. The Supreme Court’s infamous Citizens United decision, which overturned restrictions on independent campaign expenditures, brought about unprecedented levels of campaign spending—and opened another avenue through which those with resources can exert greater influence in the political process. The median congressperson is far wealthier than the median American household, making it more difficult for elected officials to empathize with their poorer constituents and prioritize policies that reflect their life experiences. Taken together, these patterns result in policymaking that favors the preferences of wealthier citizens and tends to ignore the interests of the poor.

Low-income Americans are trapped in a devastating cycle of political underrepresentation and economic stagnation. To escape this feedback loop of mutually reinforcing political and economic inequalities, we need structural changes in our political process—including automatic voter registration, restoration of the Voting Rights Act and public financing of campaigns. We also need to recognize that economic inequality is not just a troubling set of statistics—it is an existential question for democracy itself.

Democrats and Republicans may disagree on how, and even whether, we ought to deal with socioeconomic inequality. By framing the problem in terms of political equality, perhaps we can find some common ground. Accountability, equal citizenship and representative government are democratic ideals that all Americans of good conscience ought to take seriously.

At this time next year, a few weeks after the results of the 2020 elections are known, I personally hope to be celebrating Democratic victories—and unprecedented campus voter turnout, of course. However, these short-term wins will be superficial unless our elected officials truly commit themselves to the idea of political equality. After a campaign season that is sure to surface our worst divisions, I hope we can rally around a shared moral vision and work together for a democracy that works for all.

Contact Courtney Cooperman at ccoop20 ‘at’ stanford.edu.