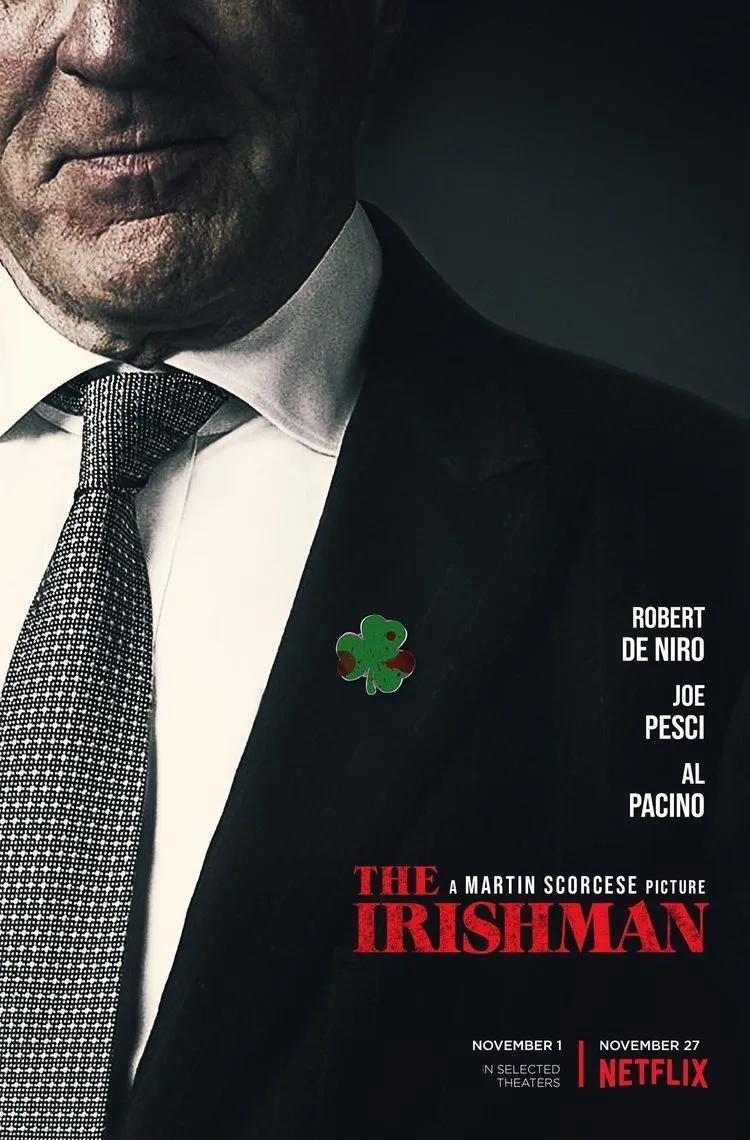

Martin Scorsese’s latest film “The Irishman” has been named an “American epic crime film,” an apt description for a three-and-a-half-hour movie featuring some of the biggest names in Hollywood (De Niro, Pacino and Pesci) that follows the Bufalino mafia family in Pennsylvania from the 1950s to the 1970s. “The Irishman” doesn’t do subtle. “The Irishman” doesn’t do quiet. And “The Irishman” certainly disregards bathroom breaks.

The film opens with Frank Sheeran (played by an electronically aged Robert De Niro) sitting in a retirement home, speaking directly to the camera about his life working for (and eventually alongside) the mafia. The computer-generated alteration of De Niro, which appears older in the “present” world of the film and younger in its flashback portions, has been highly anticipated, and the execution is surprisingly delightful. Even while appearing twenty years older than his actual age, De Niro harnesses the same sincere command of the camera, the same sharp edge and the same tight grip on the audience that he has had since the start of his career.

Titled onscreen as, “I Heard You Paint Houses” (the name of the book by Charles Brandt, on which the film is based), “The Irishman” is, at its core, a story of history. It is the past told through the present — through flashbacks, sprinkled with De Niro’s insightful (and sometimes frightening) voiceovers. He teaches us everything from daily mob routines to picking the best gun to carry out a hit. We follow Sheeran as he moves through the ranks, watching him transform from a lowly driver to the mob’s most trusted (and fatal) hitman.

Steven Zaillian (Oscar-winning writer of “Schindler’s List,” “Moneyball” and “Gangs of New York”) has written a quick and poignant script; he doesn’t hesitate to carve out space for witty lines — such as, “I work hard for ‘em when I ain’t stealing from ‘em” — while allowing more moving moments, like, “‘Were you afraid of dying?’ ‘Always afraid.’” Characters in “The Irishman” are at once fresh and familiar to us: irreverent children at heart, playing with their power and shocking us with their audacity.

Scorsese incorporates superb symmetry and shapes in his cinematography, combined with a supremely timeless soundtrack that leads us out of the cushioned seats of the movie theater and into the film itself. We stay with characters through long shots with few cuts, steeping us in their perspective through both point-of-view shots and wider, long-angle ones. Where we’re placed as the viewer changes: in cars, above tables, seemingly hidden around corners. This style of “The Irishman” makes it a petulant film, boldly stubborn and unapologetic. Its timing is at once comic and dramatic, as a shot will freeze at the most (in)opportune moment to show the name, position and cause of death of the prominent criminal on screen.

Where “The Irishman” may fall flat to some viewers is in its namesake. Though Sheeran’s primary duty in the film is as hitman — and he does become entangled in the complexities of his bosses — that duty transforms him into a kind of mirror protagonist, not too involved in the outcome nor the decisions of his own life. His loyalty and responsibility are made clear to us from the beginning, allowing “The Irishman” to be a mafia story indeed: one of family and love and blood and money and power, but all filtered through a character that seems to have not much more agency than ourselves in the audience.

The length of “The Irishman” also may take a toll on the viewer, and the viewing experience ultimately feels like two different films. By the time we are comfortable and excited about the mob world into which we’ve entered, there are still one and a half hours left, and the plot becomes muddled once the animosity and suspicion among gangsters grow. Like Frank, we feel caught in the middle, yet the story winds around an actual complex goal. The climax feels inevitable and not too surprising, almost barring “The Irishman” from setting itself apart from other films of its kind. Tangibly a passion project for Scorsese since 2009, “The Irishman” will intrigue fans of the genre. A comical, colorful and brooding exploration into notorious crime and nefarious allegiance, “The Irishman” asks us to realign our preconceptions of storytelling and character-building. To take the film at face-value seems naïve; recognizing Scorsese’s history and dedication to his craft intensifies the cinematic experience.

A previous version of this post incorrectly referred to the fictional character Frank Sheeran as Frank Irish. The Daily regrets this error.

Contact Marika Tron at mtron ‘at’ stanford.edu.