I’m just going to come out and say it: I don’t like poetry. At least, I thought I didn’t like poetry for the 21 years of my life up to the beginning of this quarter. I was so sure of it, too. Poetry, in my feeble mind, was either too difficult to understand or tried too hard to be deep — two of my least favorite qualities not only in art or literature, but also in people.

Poetry, to my ignorant self, was something you either loved or hated, and saying, “I don’t love it, but I appreciate it” seemed like a copout, because the truth was that I didn’t appreciate it. I didn’t give it enough of a chance to appreciate it, nor did I know enough about what to look for in a poem to reach such a state of appreciation. Thus, when I saw that I was required to take two classes related to poetry to graduate with a degree in English with an emphasis in creative writing, I decided to take both at the same time. Let’s get this over with, I thought as I clicked around on Axess and enrolled in one class focused on writing poetry and another on analyzing it. Now, my weeks are filled with poetry, and my feelings toward it have become more complicated. At the very least, I appreciate it, and, dare I say it, I may even like it.

I went into the quarter expecting to be lectured on the various approaches required to hyper-analyze each stanza, each line, each syllable of a poem to deduce its meaning. On the first day of class, however, my professor laid out the claim: Perhaps we put too much pressure on extracting meaning out of a poem — the very pressure that elicited my previous distaste for poetry. My professor put it like this: If, while going about your life, you encountered a dog with purple spots, your initial reaction would not be to ask, “What does this mean?” Instead, you would admire and inquire about it in terms of the mere manner in which it exists in this world.

Similarly, if and when, while going about your life, you encounter a poem, you should not undermine the act of simply observing and appreciating the poem for what it is as a curious entity in the world. It is okay if something doesn’t quite make sense — in poetry, aesthetics and meaning are inherently and equally valued.

If my preconceived notions about poetry were reversed in the class that focused on analyzing, they were flipped even further in the class on writing. Rather than encouraging the use of abstractions and metaphors understandable to the poet only (and perhaps not even to them), my creative writing teacher told us that the path to the universal is through the specific. Poetic, right? It’s oddly true. Specific details in writing lend readers to relate more to the text, whether through shared experiences or the enhanced ability to imagine exactly what the writer described. Perhaps instead of “trying too hard to be deep,” as I initially thought, good poetry aims to poke deep into the hearts of readers through specific, relatable and sometimes simple language and imagery.

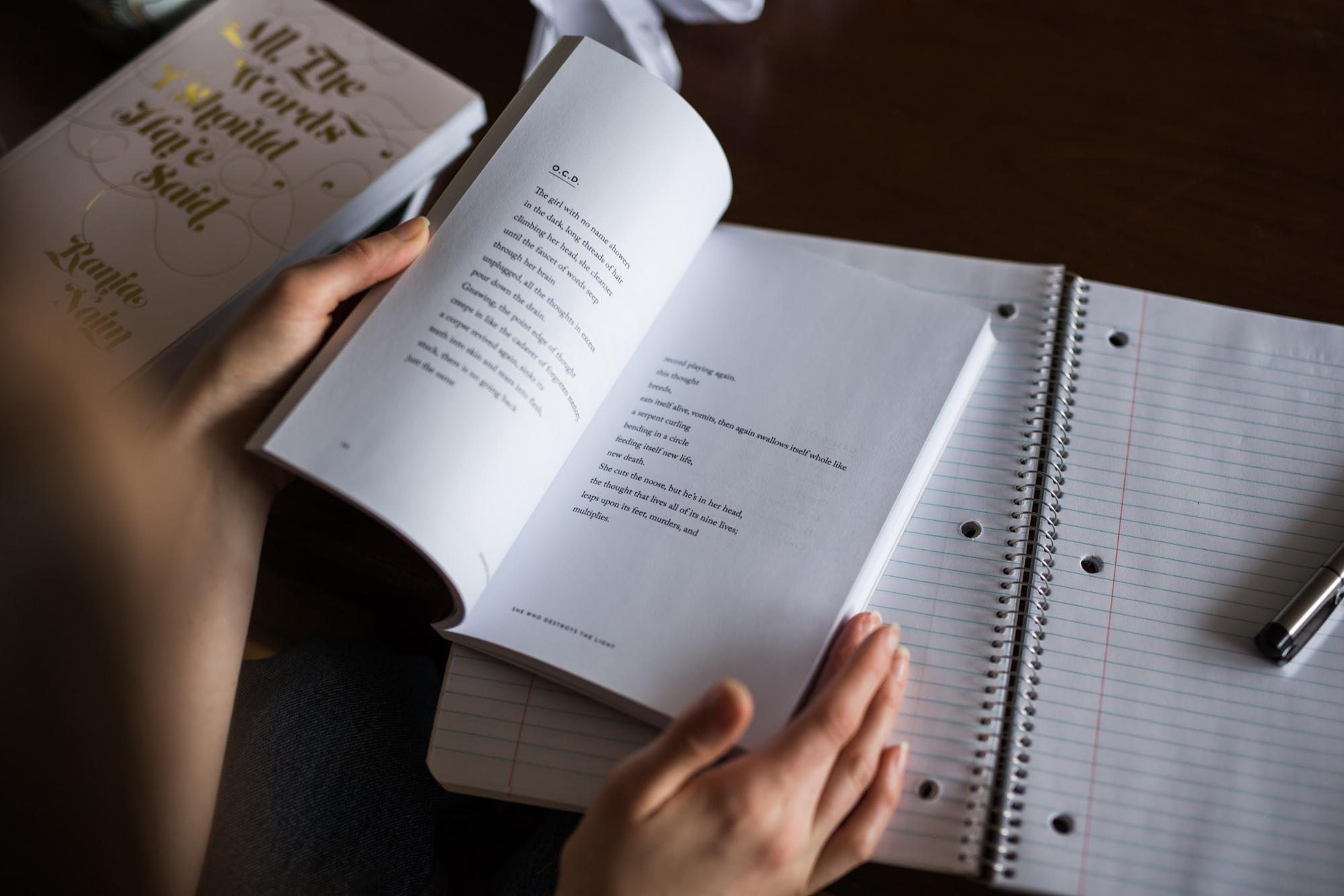

Taking these two classes requires that I write at least one and read several poems throughout the week. Perhaps my favorite thing about this newfound appreciation for poetry is the manner in which I am forced to view and inquire about the world through the lens of poems.

As my nostrils flare in the cold winter weather, as I miss loved ones that are far away, as I snack on a bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, I wonder if I should write my weekly poem on this topic. I consider — are there some things in life that are deemed “worthy” of being the subject of a poem and other things that aren’t? Are there things in my life that are “worthy” of being considered poetry?

As I switch gears and read and analyze some poems for the other class, I realize that, yes, poets all over the world and throughout history seem to have wondered the same things — and, yes, many of the small, beautiful, heartbreaking and heartwarming things in my life have been deemed worthy of poetry. In fact, they are poetry, and are the reason it exists.

Contact Angie Lee at angielee ‘at’ stanford.edu.