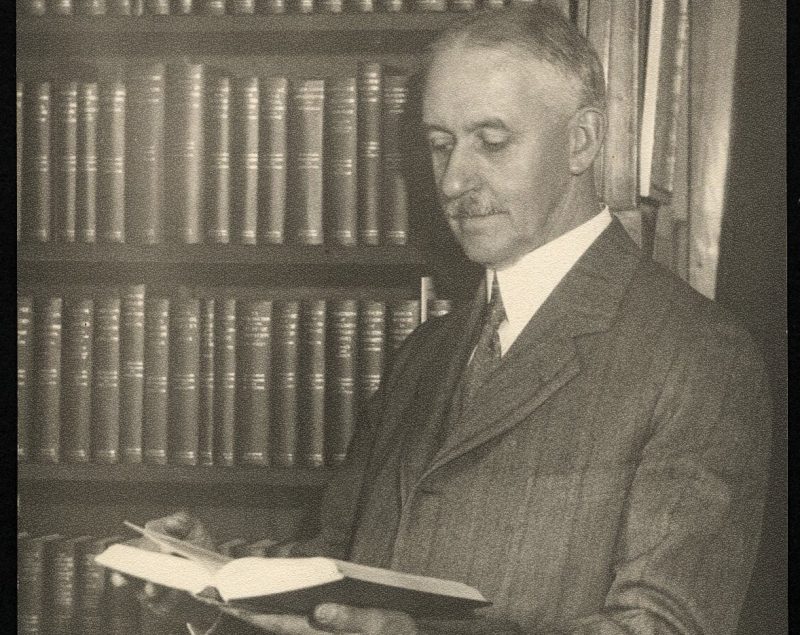

Ellwood Cubberley started teaching at Stanford in 1898 and remained until his retirement in 1933. Handpicked by David Starr Jordan, Stanford’s president at the time, Cubberley was instrumental in founding Stanford’s School of Education, serving as its first dean. One of the earliest academics in the field of education management, Cubberley helped establish the development of the American education system. After his retirement, Cubberley’s financial support led to the construction of Cubberley Education Library. For Cubberley, however, his study of education was deeply shaped by eugenics, the science of human improvement through selective reproduction based on ableism and racism.

As the “Eugenics on the Farm” series has previously explored, Stanford University played a large role in the eugenics movement in the United States. Eugenicists promoted the restricted reproduction of “unfit” populations through measures ranging from segregation to forced sterilizations during the first half of the 20th century. From teaching eugenic theory in classes to promoting eugenic research, many Stanford academics helped advanced this new and harmful science, including Ellwood Cubberley.

For Cubberley, efficiency was king. A successful educational venture was one that could pump out the brightest students at the fastest rate. In his 1916 book “Public School Administration,” he elaborated on this point: “our schools are, in a sense, factories in which the raw products (children) are to be shaped and fashioned into products to meet the various demands of life.” For these “factories” to produce such children, they required the “elimination of waste” and the “continuous measurement of production.” This analysis may feel like satire to the modern reader, but Cubberley was thoroughly devoted to this cult of efficiency, as it has come to be known.

To reach peak efficiency, Cubberley encouraged schools to regularly test both teachers and students and measure their progress. He argued that schools should be run like businesses with regular reports that could set standards and create strict expectations for both students and educators. Like quality standards on a production line, quantifiable measures of student’s educational success could determine who was fit to continue and who was better left behind.

Cubberley coupled his emphasis on educational efficiency and production with a science emphasizing biological efficiency and reproduction: eugenics. Cubberley asserted that education might instead best be compared to agriculture, where “heredity and the growth-progress modify production.” Just as plants are bred for peak production, so too could human heredity play a role in the production of the perfect students. If the goal was to create the brightest students with the least amount of effort in the most efficient possible manner, why not only focus on those whose heredity lay the foundation for intelligence and eugenic fitness?

Alongside his colleague Lewis Terman, Cubberley did exactly that. While Terman developed the Stanford-Binet IQ test to quantify inherent (and inheritable) intelligence, Cubberley helped to popularize it as an educational tool. Believing that identifying those born with eugenic intelligence could increase efficiency, Cubberley promoted the use of standardized intelligence tests to determine who was worthy of an education. Like Terman, Cubberley understood intelligence as controlled by heredity, controlled by “racial and family inheritance and nothing within the gift of schools.” Under Cubberley’s eugenic framework, education could not increase intelligence, only “make useful intelligence which the child brings with him to school.”

This method of locating eugenically gifted students for education was explicitly racist. Beyond utilizing Terman’s IQ test, which was developed with the assumption that non-white races were inferior, Cubberley viewed certain races as fundamentally less intelligent with less desirable cultures. For instance, in his 1909 book “Changing Conceptions of Education,” he described Southern and Eastern European immigrants as racially “illiterate, docile, lacking in self-reliance.” Like other eugenicists, he feared the immigration of these populations would impact the racial health of the nation: “their coming has served to dilute tremendously our national stock.” Because of this, Cubberley was a proponent of Americanization, the teaching of “American values” in hopes of removing the culture of immigrants. He promoted a system of education that favored certain populations for their eugenic fitness while exerting control on unwanted groups.

It is often said that people are products of their time, shaped by external forces and thus beyond the judgement of present people. While this contains a hint of truth, such criticism ignores that people with power create their time, that they shape it with their actions. Ellwood Cubberley and his cult of efficiency transformed the way education functioned, emphasizing production, cost reduction and standardized intelligence all shaped by race and heredity. Nowhere else is the lasting impact of his legacy seen more clearly than at Stanford University, or any elite educational institution. We live every day of our lives surrounded by tests, by standardization, by institutions treating students as products.

It can be difficult to take these constant evaluations as personal, as reflective of our own self-worth, especially for groups who have historically been deemed as lesser. They feel timeless, ahistorical: a failing grade is, and always has been, a sign of inherent inability. But this is simply not the case. Constant educational evaluations were invented by humans, shaped by eugenics and racism. Ellwood Cubberley and his cult of efficiency feel timeless, but are anything but. They have a history. And by understanding and acknowledging this historical interplay between eugenics and education, we can take the first steps towards creating a more just educational system, and perhaps even a kinder one.

Contact Ben Maldonado at bmaldona ‘at’ stanford.edu.