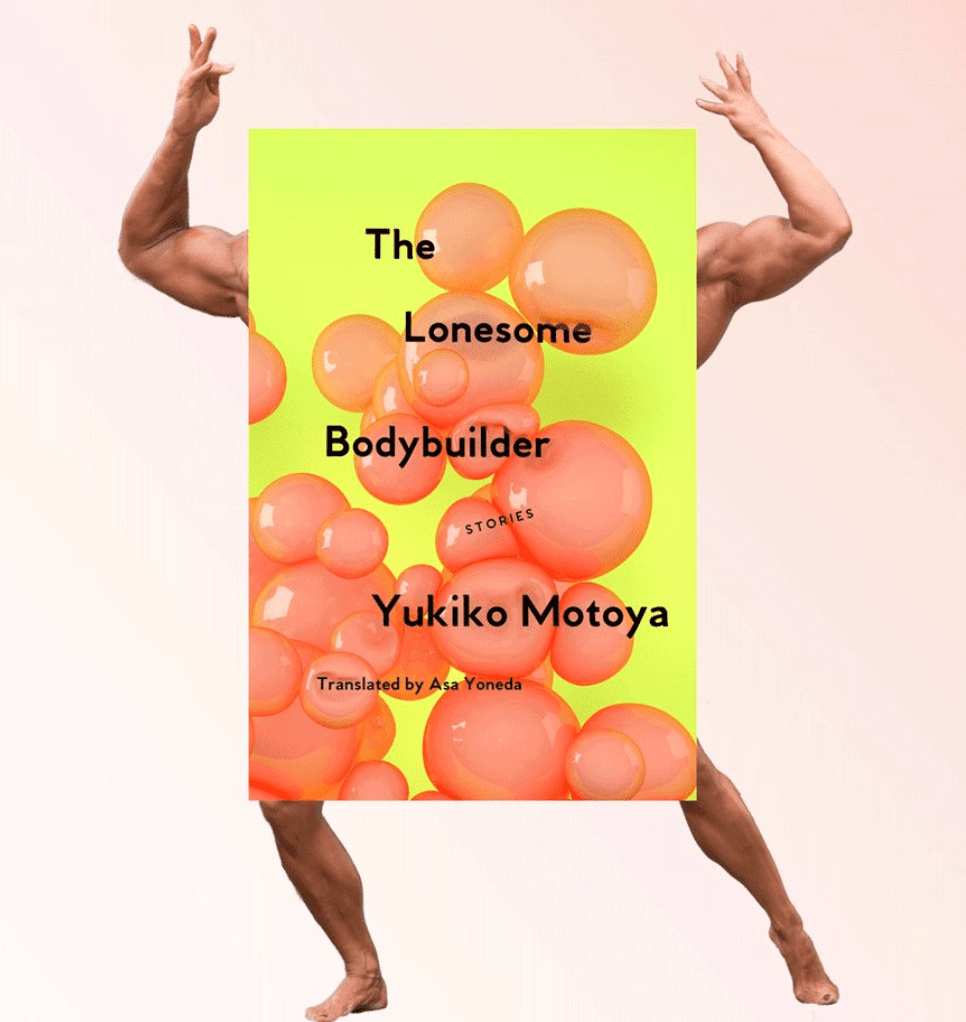

Haruki Murakami has tended to crowd out other Japanese fiction writers in the American market. Not today. Yukiko Motoya’s story collection “The Lonesome Bodybuilder,” her first in English, will appeal to readers who appreciate Murakami’s surrealism, but who lament his lack of attention to fully realized gender dynamics. In the worlds Motoya describes, strangeness is inseparable from those dynamics, which she takes to be worthy of attention.

For example, the very last story in the collection details an afternoon between a husband and wife who argue about the wife’s seatbelt scratching the door of the husband’s new BMW. Normal for many a bourgeois couple, right? Except the husband is made entirely of straw, and during the course of the argument, musical instruments mysteriously begin to tumble out of the hems of his body. The story doesn’t give an explanation for this turn of events, but it leaves the reader with a new metaphor to view arguments in a relationship, particularly from the perspective of a wife.

Most of the stories go in subtler directions as they deal with the troubled relations between men and women. The longest of the stories, “An Exotic Marriage,” more a novella than short story, recounts the experience of a woman who notices that her face is starting to resemble her husband’s, neither of which seem human-like at all.

“An Exotic Marriage,” like many of the other stories, is about what it means to be independent within the structure and limits of a relationship. Motoya asks the question of whether you absorb your partner’s personality the more long-term and committed the relationship is. Can you still retain a part of yourself in such a relationship, or do you slip on, mask-like, the characteristics of your lover? How can a woman who is financially dependent on a man maintain her spiritual independence?

Some of the stories, however, have little to do with romantic relationships, and emphasize the surreal over the interpersonal. One such story, “Typhoon,” follows one girl’s discovery that umbrellas can be used as sails for flying. At a train station she listens to an old man in rags tell her the story of a boy living in the jungle. The boy fights his fellow tribesmen for a foreigner’s umbrella, believing it can let him fly – only to die in the fight. The girl, listening, is entranced by the story. She looks down the train tracks and sees a swarm of commuters flying around in the summer storm.

Motoya takes creative premises and spins them into just-believable, always thought-provoking stories. A few of these failed to develop enough of an emotional effect (“Paprika Jo” and “How to Burden the Girl”), since it seems those stories concern themselves more with outlandish conceits than the psychologies of their characters. Nevertheless, they have a poetic atmosphere of ghoulishness, of nature’s inscrutable mischief. Asa Yoneda, the translator of this collection, manages to render this atmosphere in English with ease.

This atmosphere contains both magical and surreal elements, with the psychological sheen of a folktale. But what strikes a reader as the strangest ingredient in Motoya’s stories is the unexpected reasonable tone throughout. Clearheaded and understated, the narrators in each first-person story combine the creepy horror of Kafka with the ice-cold frankness of Raymond Carver.

The unflappability of the narrators, their penchant for calm responses to unnatural events, drives the stories’ dynamism. Many of Motoya’s stories concern themselves with domestic strife, and the characters react as if a woman with pink hair who cries tears of blood is just one normal bump in the road of domestic life. But that attitude of normality the narrators possess in these situations creates a reading experience all the less normal. Their decidedly bizarre approaches to bizarre events shake us to question how normal normality really is. When we work, when we clean, when we talk with our lovers, might the expected response we have to these activities be the strangest way to feel? Why do we produce “normal” reactions when life is in fact absurd?

Of course, Japan’s authors offer more than Motoya’s brand of absurdity. I recommend Mitsuyo Kakuta or Amy Yamada if you’re interested in Japanese fiction less zany than Murakami’s or Motoya’s.

“The Lonesome Bodybuilder” pokes at the boundaries of respectable society by placing “normal” members of society in abnormal situations. Motoya takes aim especially at the expectations humans place on women in the name of normality and “common sense.” But beyond the confines of social critique, Motoya’s work will impress anybody who has a taste for well-imagined dreamworlds.

Contact Scott Stevens at scotts7 ‘at’ stanford.edu.