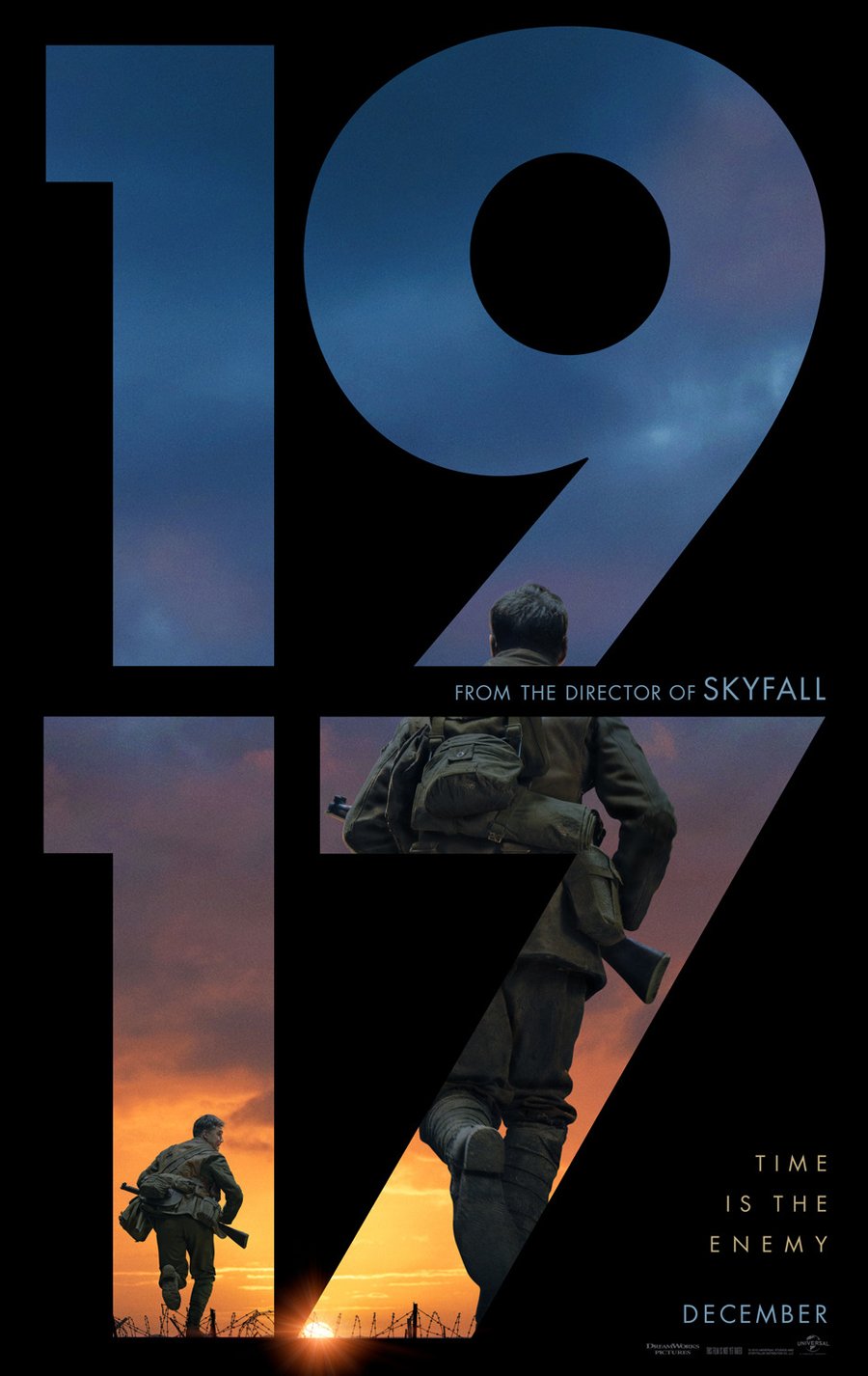

Hollywood has long had a fascination with war. From Lewis Milestone’s “All Quiet on the Western Front” to Steven Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan,” auteurs have frequently mined the complex moral themes and powerful imagery associated with war to create impactful cinema. Sam Mendes’ “1917” adds to this extensive canon. Designed to look like it was shot in two hour-long takes, “1917” manages to breathe new life into the familiar WWI genre through awe-inspiring camerawork. In “1917,” the camera is almost a character of its own, tracking our protagonists as they traverse war-torn landscapes and meander through claustrophobic trenches. It is often difficult to comprehend how some of the sequences were even shot, let alone so seamlessly – one particular scene involving running water is truly mind boggling. Still, despite its technical prowess, “1917” is not a perfect film. The one-shot format can feel rather limiting, especially concerning the film’s narrative and emotional beats. Nevertheless, I would still recommend “1917” as a must-see, simply because the camerawork needs to be seen to be believed. Mendes’ steadfast commitment to his vision ultimately pays off.

In “1917,” Mendes tracks the mission of two young soldiers, Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay), who are tasked with delivering a message across no man’s land to warn British troops about an oncoming enemy trap. Because the film is shot in real-time, there is an unrelenting sense of urgency felt throughout each scene. This constant thread of tension helps to counteract the relative simplicity of the film’s plot and the surprising lack of action — there were far fewer explosions and gun fights than I would have expected.

The chemistry between the two leads also helps carry much of the film’s absence of plot. Chapman’s upbeat attitude works as a perfect foil to MacKay’s more stoic cynicism. The banter between the two feels both real and incredibly lived-in, as if the two soldiers had indeed spent a great deal of time together kicking around in the trenches while waiting for orders. Unfortunately, both characters are never fully fleshed out, as the film only hints at vague back stories.

This is not to say that the film is boring, however. It almost never is. The immersive production design and striking cinematography transport the audience into the horrific, visceral world of trench warfare. Likewise, Mendes’ tracking camerawork makes the audience truly feel as if they are a part of the soldiers’ quest, a silent third party being brought along for the ride. Still, it is clear that the visual gimmick of one long shot limits the narrative to focus on one straightforward mission. As a result, from a plot perspective, the movie offers very little surprises.

Likewise, the one-shot format reduces the impact of some of the film’s emotional beats. Because the movie never cuts, or goes to painstaking effort to disguise any cuts, emotional moments are barely given any time to breathe. Although Mendes occasionally does slow down the non-stop pace of the film for quiet scenes of poignancy, it is not long before we are thrust back into the mission. As such, the film’s emotional moments never really land. Before the audience can internalize the impact of what just happened, the film quickly moves on.

Nevertheless, despite its relative lack of depth, “1917” is still a thoroughly enjoyable film. Mendes’ technical finesse and bold, stylistic choices manage to elevate a simple, uncomplicated story to a suspenseful feast for the eyes. With every sequence seeming to one-up the previous one in terms of cinematic spectacle, “1917” effectively recreates the atrocities and hollowness of WWI in a dynamic, enveloping manner.

Contact Paolo Vera at jpvera ‘at’ stanford.edu.