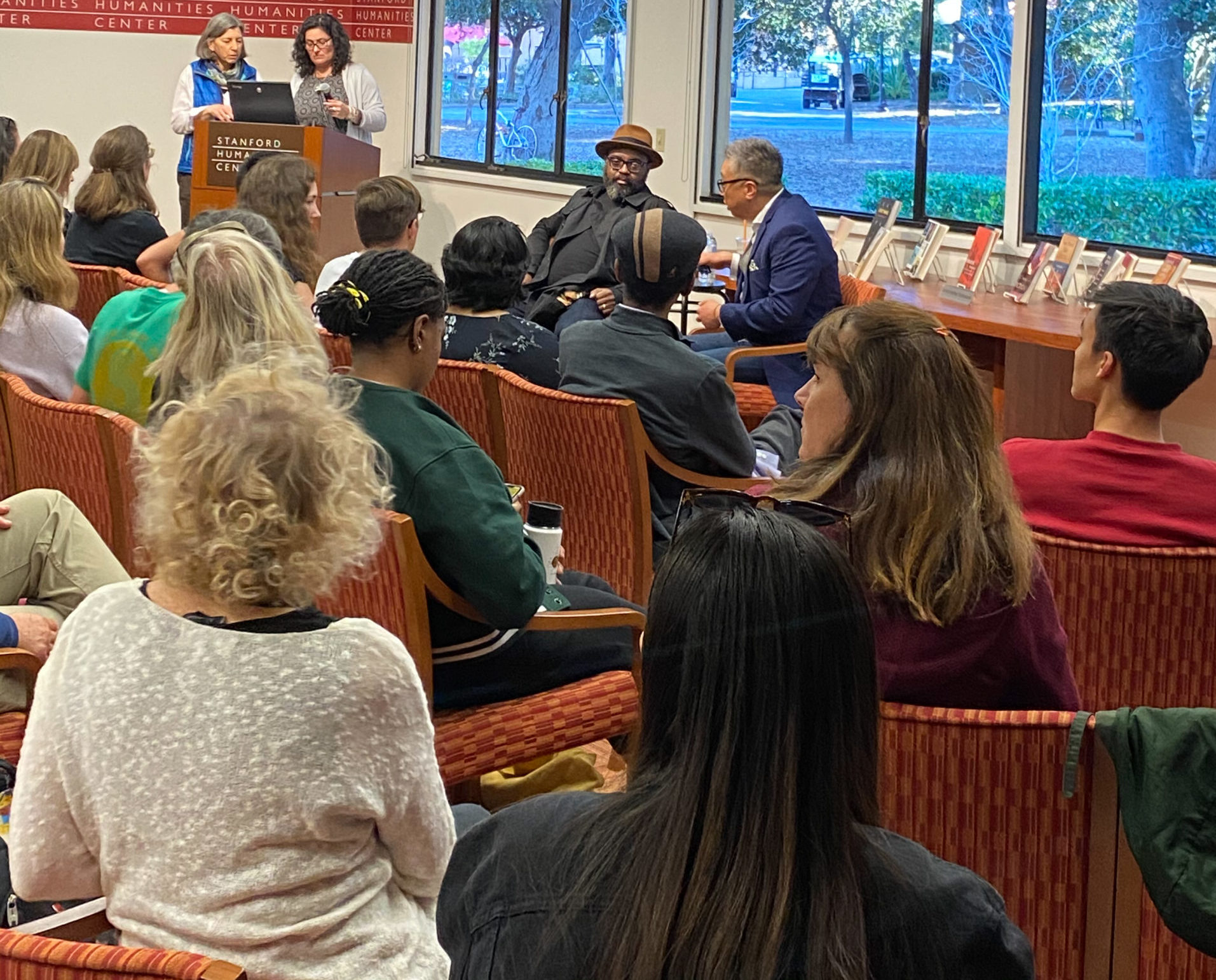

Renowned poet, 2018 Guggenheim fellow and 2018 National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) fellow Reginald Dwayne Betts came to the Stanford Humanities Center on Tuesday to discuss his work “Felon: Poems,” as well as his journey from prison, then to poetry and, finally, to studying law.

Betts, who served nine years in maximum security prison after being tried as an adult for a carjacking when he was 16, went on to attend the University of Maryland and Yale Law School. He has since written multiple award-winning works, earning him recognition like the NAACP Image Award and numerous fellowships.

Betts is currently pursuing a Ph. D. in law from Yale.

On Tuesday, Betts began by reflecting on his first book, “A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison.” Though the book detailed his time in prison, Betts “wasn’t going for whatever salacious thing allows you to capture the zeitgeist of American hunger for suffering,” he said.

The book was written from the perspective of a 16-year-old boy.

“I was an honor student, although I don’t like to say that,” Betts said. “I frequently resisted saying that because we always find a frame for somebody … I didn’t want the reader to imagine that they could have empathy for me because I was smart — that they could automatically say, ‘He wasn’t like those other kids.’”

When Betts was 16 years old, he was arrested by the police for carjacking, robbery and possession of a gun. When he was caught, Betts said, he confessed: “The thing is, when you get arrested, you confess.” He spoke of the “burden of guilt” and wanting to tell someone what he had done, even if it was a police officer. As a 16-year-old being tried as an adult, faced with the potential of a life sentence, Betts said he was too young to recognize the gravity of his situation.

In high school, he had aspired to be an engineer, but while in prison he decided to become a writer, without knowing what that meant. Then, in solitary confinement, someone slid “The Black Poets” by Dudley Randall into his cell. Betts said it had a “profound effect on how he saw the world,” and in that moment, he decided to be a poet.

Betts said conversations he had in prison helped him to craft his poems; deep conversations with fellow inmates contributed to his belief that poems could reveal a much fuller picture than a story.

“So much of a poem is trying to understand, on some lower frequency, what it means to exist in the world,” he added.

“Felons: Poems” is a collection of poetry covering themes surrounding the experience of ex-convicts, ranging from domestic violence to fatherhood. But, Betts said, the goal of his work isn’t necessarily to humanize felons: “I think I’m trying to humanize the reader, actually.” In writing his poems he aimed not to improve his image or the image of people like him, he said, but rather to have his audience “walk away from the page embracing their humanity in a way they haven’t been.”

“A lot of what’s in the book is what it means to be a person,” Betts said. “I think I was trying to tell you something about what it means to be alive.”

When deciding to pursue a career in law, Betts wondered how he could connect “the world of poetry with the world of law.”

Betts said that his identity as a poet provides him with a unique perspective on the law. To Betts, poetry allows for insight into what gets left out of the courtroom.

“As an artist, I get to be an advocate for some notion of truth,” he said.

Contact Ella Booker at ebooker ‘at’ stanford.edu.