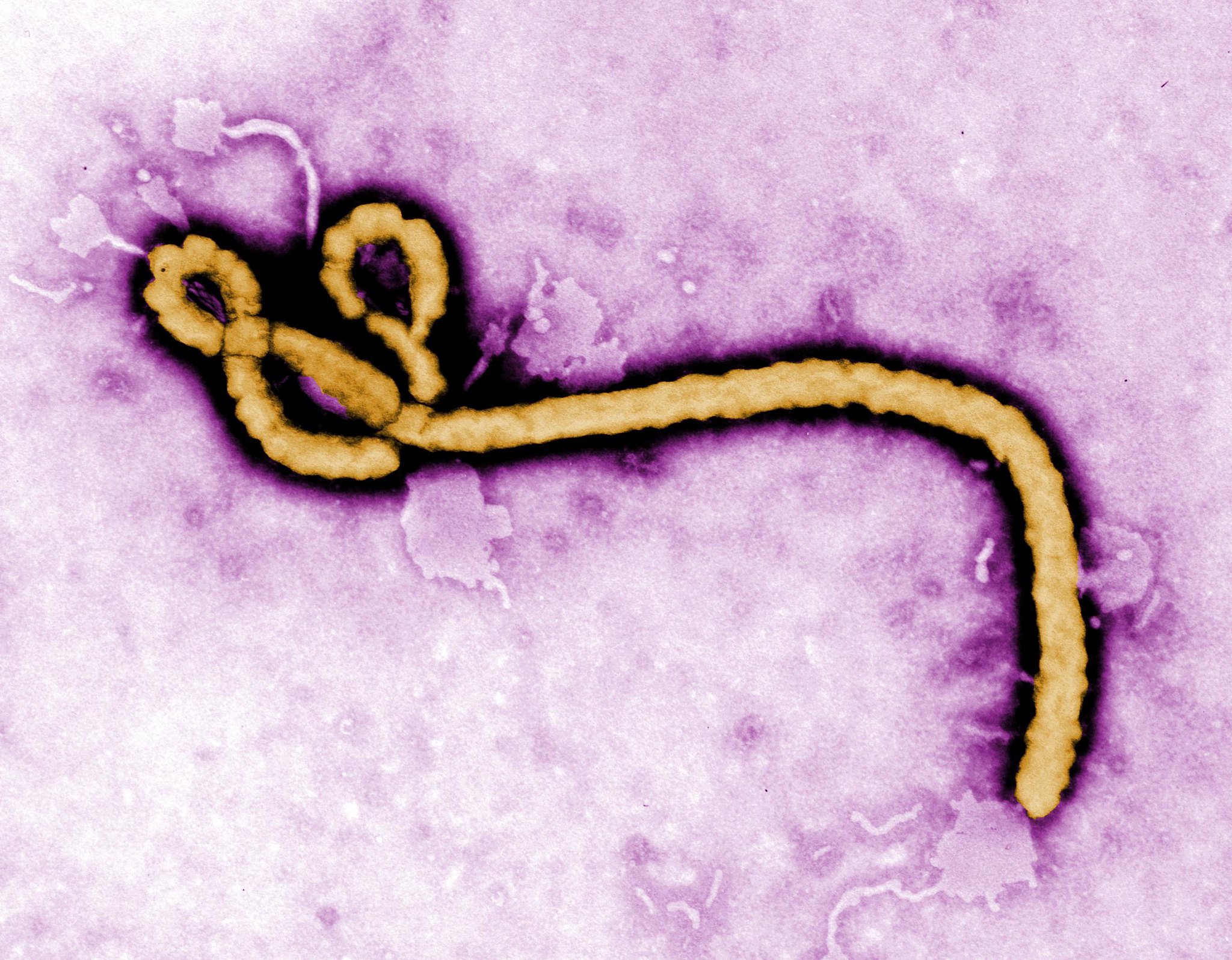

Last December, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the release of Ervebo, the first vaccine approved to combat the current Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). For the past few years, scientists have raced to find a vaccine that could stop the highly infectious disease from devastating more communities.

“The vaccine originated from a trial that began in Guinea during the 2014 epidemic, and it uses a glycoprotein from the Ebola virus in order to activate an immune response,” Nahid Bhadelia, an infectious diseases physician who provided front-line care to Ebola patients during the past two epidemics, told The Daily.

According to the World Health Organization, Ebola has a fatality rate between 25% and 90%. The current epidemic has infected over 3,300 people in the DRC, where it has been present since 2018. This pandemic follows on the footsteps of an outbreak in West Africa that killed 11,316 people during between 2013 and 2016.

“Viruses are extremely diverse and can evolve quickly, allowing for spillover into other hosts and making it challenging to control infection,” said Collin Closek, a teaching fellow for the course THINK 61: “Living with Viruses.”

The trial that preceded Ervebo’s FDA approval consisted of 3,537 individuals who lived in communities afflicted with Ebola, and each person received either an “immediate” vaccine or a 21-day “delayed” vaccine. The vaccine proved to be 100% effective in preventing Ebola in the 2,108 individuals given the “immediate” vaccine and only effective in 10 out of 1,429 individuals given the “delayed” vaccine. The vaccine was tested on individuals in Liberia, Sierra Leone, the United States, Spain and Canada.

Although the FDA has only recently approved the vaccine for use in the United States, the vaccine has already been used on over 258,000 people in at-risk communities across the world, Scientific American reported.

“Vaccination is essential to help prevent outbreaks and to stop the Ebola virus from spreading when outbreaks do occur,” said Peter Marks, head of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in an interview with Scientific American.

But there is still a lot of distrust and misinformation surrounding the Ebola epidemic, Bhadelia said. Ebola’s highly infectious nature causes patients to feel so isolated and dehumanized that many do not come in for treatment until it’s too late. The current epidemic in the DRC is also complicated by violent political conflicts, which means that individuals must often put their physical safety at risk in order to seek care. The large death toll caused by both the virus and the conflict has caused many patients to question who they should trust.

“People are burned out from the disease and the violence,” Bhadelia said.

She added that this lack of trust also stems from a general distrust in the government and foreign aid workers, adding that treatments and vaccines will only be successful if communities themselves are given the chance to lead the efforts.

“Would you rather be treated by a foreigner or by someone who understands your language?” Bhadelia asked.

Contact Sophia Nesamoney at nsophia ‘at’ stanford.edu.