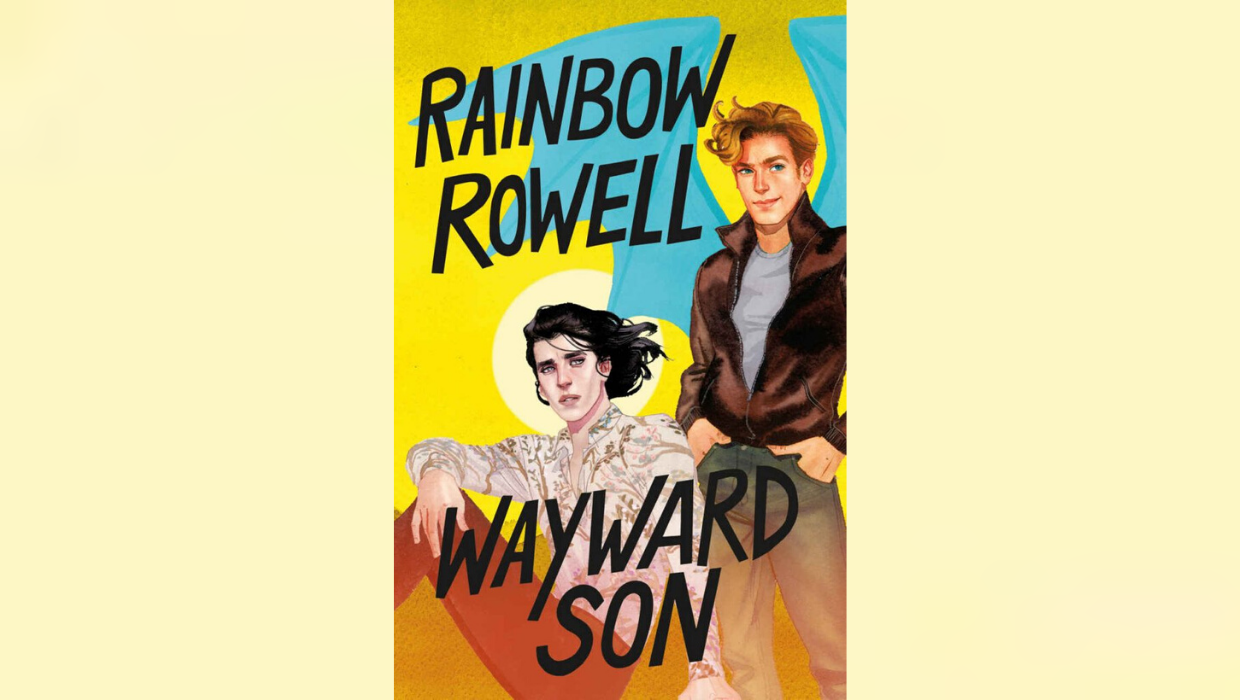

Inspired by Harry Potter’s world of Magicks (magicians, sorcerers, witches, the sort), slow-burning romances, fantastical creatures and absurd spells — ranging from “float like a butterfly” to “these aren’t the droids you’re looking for” — it’s no surprise that Rainbow Rowell has delivered a wondrous sequel to her Simon Snow series, “Wayward Son”.

“Wayward Son” continues a year after the novel “Carry On” finished. As the trio of Simon, Baz and Penelope have fallen into a desperate stasis, Simon falls into a feeling of purposelessness since his magic left him. Rowell immediately establishes a shift in Simon and Baz’s romance — both partners dread each other’s emotional reserve. Adventure presents itself when Penelope proposes a scheme to travel to the United States to visit her long-time boyfriend, Micah, and save their old school friend, Agatha, on the basis that Agatha doesn’t answer Penelope’s calls and must, therefore, be in grave danger (though, apparently, she is not — the novel is split between the four perspectives of its characters).

The trio, inevitably, finds trouble when Micah breaks up with Penelope, vampires attack a Renaissance festival, demons track them into a “quiet zone” (wherein Magicks hold no magic) and Agatha, it turns out, really is in danger. With the help of new characters — Shepard, a curious Normal (Rowell’s equivalent to Rowling’s Muggle), and Lamb, a sympathetic vampire — “Wayward Son” turns out to be as exciting an adventure as the first installment in the series.

Without a doubt, Rowell does well to reincorporate the successful elements readers praised from “Carry On”: a slow-burning romance, imaginative world-building, and beautiful exploration of the theme of displacement. As its predecessor, “Wayward Son” looks at new concepts of magic and fantasy in the United States, exploring new terminology, spells, fantastical creatures (like dormant dragons disguised as mountain ranges), “quiet zones” and vampire empires. Remarkably, Rowell also details the development of a relationship in her sequel — Simon and Baz’s romance. While in the previous book their relationship was impeded by Simon’s own rivalry with Baz, in “Wayward Son,” Simon is reluctant to believe he deserves affection, and Baz is timid for fear of losing Simon. The two protagonists are excellent devices for highlighting the theme of displacement. While Simon is learning to be a Magick without actual magic, Baz is working to embrace his vampiric nature despite the Magickal society’s bias against vampires.

Beyond these successes, Rowell scores more by introducing new characters, Shepard and Lamb. Shepard, a cursed human with a curiosity for the magickal, becomes a loyal guide to the trio as they navigate the United States, and who quickly becomes an endearing character. Lamb, the king of vampires in Las Vegas, is presented as a mentor-romantic figure toward Baz, allowing readers to learn of the peaceful, domestic Las Vegas vampires.

Despite the book’s triumphs, I felt presenting Lamb as a romantic character for Baz created unnecessary jealousy and had me confused by Baz’s interest in Lamb. While she could have created romantic tension between her two protagonists, Rowell instead complicated an already troubled relationship and patched it up as if nothing had happened. Though Rowell’s antagonist, a Silicon Valley blood-transfusing vampire, gives the narrative an iconic final battle and purpose, his mission felt entirely unoriginal, even reminiscent of Elizabeth Holmes. The magical bloodline transfusion narrative has been used in most fantastical works — “Twilight,” “A Discovery of Witches,” “City of Bones.” It makes sense why this narrative is so often rewritten — it introduces world-building elements. But, in Rowell’s sequel, it reads as an excuse for readers to enjoy a delightful montage of the trio-turned-quartet roaming America.

Also noteworthy: Rowell incorporates today’s news in referencing Elizabeth Holmes. Similarly, the California setting lends itself to evaluating the “fake culture,” high executives and influencers, as whom Californians are stereotyped. Hilariously, Ginger, Agatha’s close Californian friend, obsesses over “activation” percentages, implicative of Silicon Valley’s culture of efficiency.

Regardless, Rowell leaves readers with much unresolved, unanswered and unfinished — perfect for a third installment. “Wayward Son” was entirely delightful to read, its successes far easier to find than its weaknesses.

Contact Roberta Gonzalez-Marquez at robygzz ‘at’ stanford.edu.