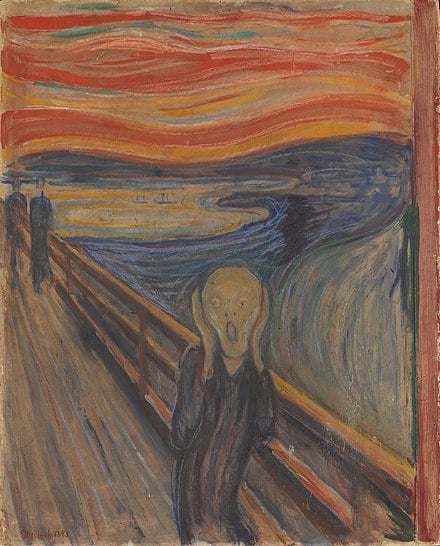

Much like its subject figure, Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” (1910) has become a ghostly apparition of its former self — a process researchers believe is only likely to continue.

According to an article from The New York Times, the cadmium yellow pigment present in several aspects of the painting’s background and forefigure is gradually turning to white. Through a process called oxidation, which occurs naturally over time with exposure to light, the yellow-hued cadmium sulfide is being transformed into cadmium sulfate and cadmium carbonate, both of which are white-colored compounds.

Naturally, Munch is just one amongst the crowd of famous painters affected. The novel yet volatile synthetic paints popularized by the expressionists and impressionists of the 1880s through 1920s are all subject to these chemical changes.

Munch’s well-known contemporary, Vincent van Gogh, utilized a similar set of chrome yellow pigments which have the tendency to turn from pale yellow to olive green. “Sunflowers” (1889) is perhaps the best example of this, the hues of the stems, flowers and background gradually darkening to a greenish-brown color. Similarly, the ocean blue walls depicted in his 1888 masterpiece, “The Bedroom,” were once a stark purple, their current coloration the result of the oxidation of red pigment to white.

So what does this all mean for us today — the academics, historians, researchers, art enthusiasts and casual appreciators? Obviously we can all gather around and make comments like “Oh, ‘The Scream’ is more dreary now, how fitting” or “I like the blue walls better than the purple,” but given the intricacies of the art world and its patrons as well as the immense monetary value of some of these art works, an assessment of how degradation may affect perceived values of authenticity and worth seems appropriate.

To conserve or to not conserve? This seems like a fair place to start, given the human tendency towards direct action. The year 2016 saw the rise of macroscopic X-ray powder diffraction, a new chemical mapping technology that allows researchers to detect materials within the pigments of a painting without having to physically handle (and likely damage) the painting. Information gleaned from this technology can be used to generate digital reconstructions of the original paintings. But are these digital reconstructions “enough” in the sense that they satisfy our viewing pleasure and innate desire for “authentic” art? What about cases concerning art collectors, who may prefer the traditional techniques of direct restoration?

In discussing preference, there also exists the possibility of a “double standard” situation. Some paintings might actually “ripen” with recoloration while others simply “fade.” Should we view the ripened paintings as superior for withstanding the test of time? Of course, the two outcomes are not necessarily mutually exclusive either. The fading of the cadmium yellow in “The Scream,” for example, may be seen as a fitting contribution to its overall mood — a drawn out, quiet death for its subject — rather than an outright inhibitor of its legacy.

Ultimately, however, art is a reflection of the artist. Personally, I believe Van Gogh’s bold attitude towards the practice of painting itself is better expressed in the original version of “The Bedroom.” There’s a certain perky outlandishness to the purple doors and lavender walls that I more strongly associate with the novel use of vivid, seemingly arbitrary color by the post-impressionists. In other words, going with blue walls would have been far too typical for a “madman” like Van Gogh. That being said, I would still argue against direct restoration and any other methods that alter the original canvas, degraded as it may be. Sappy as it might sound, I truly believe that the artist pours a portion of his or her soul into every work of art; who are we to paint over and smother such a dynamic, spirited entity?

As the esteemed artist himself once wrote in a letter to his brother, “the paintings fade like flowers.” Despite my personal preference for Van Gogh’s unoxidized originals, his words hint as much of his own anticipation of these material issues as of a sense of acceptance and embracement of natural death. As is the case with all good things, perhaps the best course of action is to listen to Van Gogh and let these paintings pass in peace, unbridled by material concerns of authenticity and value.

Contact Carissa Lee at carislee ‘at’ stanford.edu.