Intro: Hi! We’re Mark and Nitish, and we (like most of you we hope) are practicing social distancing to help prevent the spread of coronavirus. We recognize that this is a super stressful time for a lot of people, and that many of you are being impacted by the virus in one way or another. So, we thought we’d do something that would hopefully lighten the mood. We are going to be watching and reviewing movies available on streaming platforms. Our column will be published (roughly) every week on Wednesday. We hope that you can watch along, send us your thoughts and recommend movies that you like or want us to watch. Best of luck to all of you in these trying times!

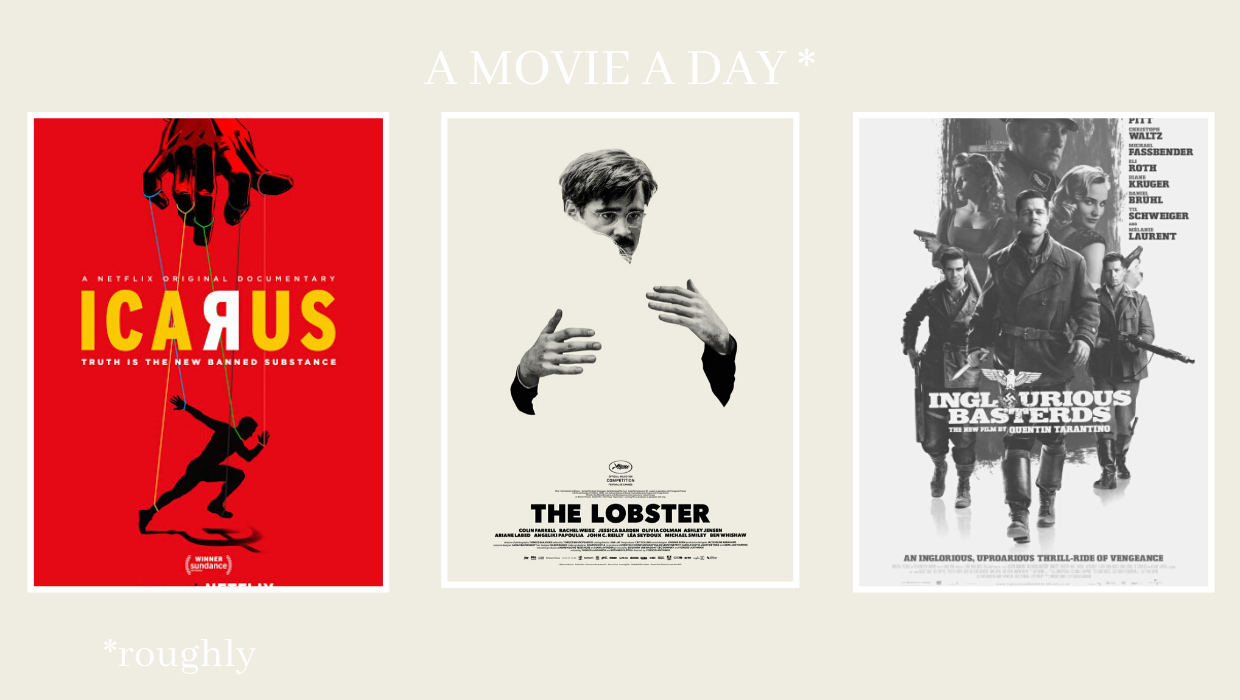

“The Lobster” (Released in 2015; watched by us on March 17, 2020)

A film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. We watched it on Netflix!

Mark:

“The Lobster” was the awkward, uncomfortable dystopia I never knew we needed. Quite frankly, I’m still not sure if we need it, but it was a positive experience nevertheless.

Director Yorgos Lanthimos depicts a society in which its people are given 45 days to find a mate, or else they are turned into an animal of their choice. Surely enough, a lot of awkward small-talk and forced first dates ensue — this is my worst nightmare. I would most likely choose to be turned into a cockatoo (or a platypus if I was feeling spicy) long before working up the courage to talk to a girl at a party. Is that why I am still single?

My personal crises aside, “The Lobster” is defined by tactful discomfort. The writing stands out with its many awkward conversations, providing us an odd amount of detail that feels abrupt and unnecessary. We promise you — cringe will ensue. The acting is stilted and artificial, though in a very intentional sort of way. There is something inhuman about our characters, both hero and antagonist, that resembles a sort of uncanny valley. The director chooses to make each shot linger onto the subject, making each cut only when it is absolutely necessary. Often, the shot keeps running, even when it feels as though it should have ended by then … like it is about time we get going and leave them alone. The overall vibe of this movie can be best described as that noise styrofoam makes when you rub them together, and I mean this in the most positive way.

“The Lobster” is sold as a “Handmaid’s Tale” for squares, or an introvert’s “Mad Max.” This film bottles up the natural and ingrained anxieties that come from unwanted social situations in order to make what initially seems like an absurd and goofy concept into a real frightening environment.

Let me be clear: This movie is an acquired taste. “The Lobster” will not work for everyone. In fact, though I recognize its proficiency, I am still not sure if it works for me — I am already quite suitably afraid of talking to other people and I did not need a movie to reinforce that. But, if the concept of a socially awkward dystopia intrigues you, it is certainly worth giving this movie a watch. Perhaps if this is what dating is actually like, then maybe social distancing won’t be such a bad thing after all.

Nitish:

I have no idea why we started with this one, “The Lobster” is seriously out there. We probably should have started a coronavirus movie watch party with something somber but heartwarming, that shows respect to the global tragedy but that has an air of resilience. Instead, we watched a dystopian allegory about the horrors of romance. (This is why you guys should start picking movies.)

Anyway, “The Lobster” is really good. I don’t want to give too much away about the plot, but the movie presents a dystopic version of a society where people are expected to be paired off in romantic relationships. Our characters are given a 45 day window to be single; after this, you get turned into an animal. The governing structures of this society are helpful though, and ship you off to a Bachelor-in-Purgatory hotel where participants frantically try to find a partner, hunting single people in the woods in order to extend the amount of time they are allowed to search for a date.

At first I thought this movie was going to be an obvious and weak allegory about how society dehumanizes single people, but as the movie went on I grew to appreciate its nuance. Where “The Lobster” adds this depth is not in the rules of its world, but in the work it does with its characters. People form connections sometimes because they are forced to, or don’t form connections because they are forced not to. But both of these states are remarkably brittle, and the movie shows us that repeatedly in different scenarios. The real connections that people formed in the movie, be they love, envy or hate, came from unexpected sources.

A central theme of this movie is the way that shared experiences — more specifically shared trauma — define these relationships. Sometimes, these experiences are distilled and gelded and turned into what characters call ‘defining traits.’ Think “fan of ‘The Office’” on Tinder, but instead with limps, nosebleeds, smiles, psychopathy and shortsightedness. “The Lobster” depicts these traits as an unstable foundation to build a relationship on, but characters still put a lot of stock in them. I think that the most interesting piece of the movie is the way that shared experiences form the basis for a relationship for the main character in an unexpected environment; near the end of the movie, our main character and his partner’s defining traits get out of sync, and the way that both characters deal with that poses the movie’s most interesting quandary just as the credits begin to roll. Personally, I think that the ending is ambiguous as to whether or not this type of shared experience is necessary for a healthy relationship, and it hints that there may be something deeper to human connection than the relatively superficial markers used throughout the rest of the movie.

One thing that I really appreciated about Lanthimos’ direction is how delicate and intentional it is. The camera often tracks movement at the same pace as the subject, but it maintains a respectful distance away from our characters. The result is a sort of sterile intimacy, as if we are respectfully watching a dissection in an operating theater. One interesting scene featured a young woman swimming in the hotel’s swimming pool. The camera glides with her as she does the backstroke, and we see men hoping to partner with her leering in the background. In another movie, I would accuse the director of pandering to the male gaze. But in “The Lobster,” where sexuality is a tool to characters as they seek to navigate the hotel (and not just a tool to trailer editors), the shot turns into a strange game of survival between the woman in the foreground and the men in the background. A few men discuss a man’s limp early in the movie, and the camera barely bothers to show it to us as the characters simply don’t have an interest in it as they are all heterosexual and have no interest in each other. The characters seem to objectify each other out of necessity, and the camera is careful to tell us when it matters. Lanthimos’ direction complements his and Filippou’s script perfectly.

In short, I think this is an excellent movie, and it intelligently questions the nature of human connection. I wouldn’t recommend it to everyone, as it is sometimes quite gory. But if you like dystopian fiction, this should be right up your alley. I would also recommend another of Lanthimos’ movies, “The Favourite,” which is just as good. See you tomorrow!

“Inglourious Basterds” (Released in 2009; watched by us on March 18, 2020)

A film directed by Quentin Tarantino. We watched it on Netflix!

Mark:

Dear reader, I have developed a mixed sort of relationship with the works of Quentin Tarantino.

He appears to be one of those directors I should like — and believe me, I’m trying. Consider his cultural imprint, his respectable filmography, and his wide collection of film awards — by now, he has accumulated enough Golden Globes and Oscars to meld down and make into a golden toilet seat. And to be fair, I am still a Tarantino novice. I have only seen two of his films, “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” and “Inglourious Basterds” – both of which are clearly infused in skill, but fail in my opinion to make me feel.

And, isn’t that the point of art? … Isn’t it? I am not being rhetorical — I would like to know. Films such as “Inglourious Basterds” tend to confuse me, because they seem to go against what I have always believed to be the point of art and storytelling: the reader, the audience, the consumer and the experience you have created for them. This does not seem to be the case of Tarantino’s work. I can’t help but feel as though his filmmaking — from what little I have seen so far — remains ambivalent to the audience. They instead serve film itself as an art form.

In “Inglourious Basterds,” Tarantino is not shy about his love for film. The dude literally uses old film reels to burn a bunch of Nazis to death. But, I think his priorities become even clearer when we consider our characters, and what little attention is placed on them. Our characters are less the point of the film and more pawns and avatars in which Tarantino shows off wicked action scenes, bloody violence and the lavish kind of spectacle that the medium allows. More people die in this movie than they are named. Little things like pathos will not stop him from making the most out of film and doing everything in his power to show off what this art form can allow. As it so happens, this art form is capable of killing fictional characters in many creative and technically impressive ways.

That’s fine, great even — but I personally think I am missing something when I don’t have the ability to feel anything about those killings. I just applaud the fireworks show for all its aesthetic majesty, despite the inevitable forest fires afterward.

But despite these odd storytelling differences, I am fascinated by one notable outlier. Shoshanna Dreyfus is arguably the only character who fits what we would consider a standard, solid protagonist. We understand her backstory — she is the only survivor of a Nazi family killed by Gestapo Colonel Landa. We feel her motives — after suddenly being forced to organize a film screening for Landa and a bunch of other Nazis, the same who’d slaughtered her family and people, we too want revenge. As an audience member, I followed Dreyfus and genuinely rooted for her. She was easily the character I was most invested in within this film’s many different storylines.

Yet she too, dies an abrupt — and arguably, narratively pointless — death, killed by a Nazi soldier who’d had the hots for her and was ticked off by her rejection. She does not even get to come face-to-face with the man who killed her family, who is set up early on to be the clear villain of the story … that stand-off goes to somebody else, with a far less personal connection to this villain.

I am struggling to make sense of Quentin Tarantino — what his works mean for me, what I think of art. But, throughout this marathon, I hope to explore his filmography more deeply. Maybe I will find some answers. I have a feeling, though, that it won’t be that simple.

Nitish:

Our second movie! This movie is impeccably directed, has a phenomenal score and has a star-studded cast that is firing on all cylinders. But is it good? Uh, sort of.

I’ll start off with the good stuff: This movie is astonishingly well-executed. The opening scene, where Gestapo Colonel Hans Landa played by Cristoph Waltz interrogates a French family about hiding a Jewish family beneath the floorboards, is the stuff of movie-making legend. I’ll use this scene to talk about some of the filmmaking that’s going on in the movie. We start off with a few picture-perfect shots of the French countryside, with a winding road coming up to the cottage. The farmer’s daughters start to warn him, and he comes to meet them. The lighting on the inside of the cottage is perfect, and it makes you feel as if you are in a painting. The dialogue is too polite, too witty to make you think that it’s realistic, but not so stilted that it makes you think you’re watching one of Aaron Sorkin’s more pompous West Wing episodes. Cristoph Waltz executes this dialogue in a simply extraordinary performance. It is rare that you can be terrified of a Gestapo Colonel, horrified at what he’s here to do, but at the same time impressed at his impeccable table manners. We start off with shots where the subjects’ faces are turned towards us, and the interrogation of the farmer starts off open and breezy. But then, as Landa asks the farmer for specifics about the missing Jewish family, Tarantino brings the camera behind Landa’s back and rests it on the other side; the shots are now a little more intimate, a little more stressed. When Landa leans forward in his seat, the camera, almost imperceptibly, moves with him, allowing the viewer to really feel the change in tone. In an inspired moment, Tarantino has the camera trace the farmer’s leg down to the floor and then drops it beneath the floorboards so we can see the Jewish family clutching their mouths so that they don’t make a sound. When Landa finally turns up the heat and starts accusing the farmer of hiding the Jewish family, the camera shifts its orientation again, this time proceeding with close-ups from the front of each of the subjects’ faces as they look at each other. The score has started to reach a feverish pitch. I’ll leave the conclusion of the scene unspoiled, but pay particular attention to one of the shots where a character is framed by a door. It is an extremely elegant composition. The quality of the dialogue, acting, direction, and all the other little pieces that make a movie a movie, stays constant throughout the movie.

But unfortunately, I can’t say that this movie is a great movie, and for the same reason that I can’t say I think that any of the other Tarantino movies I have watched are great. Tarantino has incredible skill as a director, but his movies seem only pointless exercises in skill. Dialogue is not there to give you a plot or reveal things about characters. It is there so you can be impressed with Tarantino’s ability to write dialogue. Lighting and direction aren’t there to create visual narrative. They are there so you can be impressed with Tarantino’s ability to compose a shot. There’s a moment in the second chapter where a character referred to as “The Bear Jew” (for his prodigious ability to beat German soldiers to death with a baseball bat) asks a German soldier if he got a medal on his lapel for “killing Jews.” The soldier looks up and responds “Bravery.” For a moment, you might think that Tarantino is about to start an interesting discussion about how certain virtues may uneasily coexist with a horrific and unvirtuous cause. And then “The Bear Jew” hits the soldier in the face with a baseball bat, and then hits him a few more times for good measure. “Inglourious Basterds” is a tale full of sound and fury, told by a true master in his craft, signifying nothing. Perhaps I am missing something. Perhaps there is nuance that I am overlooking, emotional context that I am blind to, narrative that I cannot comprehend. Perhaps this movie has more than I have given it credit for. But this is the third time that I have watched “Inglourious Basterds.” Each time, it feels more hollow than the last.

Watch this movie. Be impressed by the way that Tarantino moves the camera, the way that he writes dialogue, the way that his actors keep your eyes glued to the screen. But don’t be surprised when you forget it.

“Icarus” (Released in 2017; watched by us on March 19, 2020)

A film directed by Bryan Fogel. We watched it on Netflix!

Mark:

The Academy Award-winning documentary “Icarus” is a wild ride that I do not have much to say about. That is, not without some tangentially related context.

You see, dear reader, I do have a lot to say about the documentary genre — so allow me to tell a story. Throughout this past winter, I took a break from being an on-campus grump — shutting myself in my room, hissing at frolicking freshmen — to go to New York City, where I interned at a small production company called Little Monster Films. They are mostly known for their documentary work, and one of my main tasks was to marathon a whole bunch of documentaries — the best of the best that the genre has to offer. As somebody who’d, before, primarily been immersed in fiction, I found the experience especially enlightening.

Previously, I had assumed that documentaries were simply works of documentation, like an essay or a textbook. I blame a childhood’s worth of dry classroom documentaries — years and years of Ken Burn films, or the occasional nature doc when my biology teacher wasn’t feeling up to it. But, as I was exposed to wide variety of different documentaries, from the immersive narrative of “Honeyland,” the hypnotic character study that is “Little Dieter Needs to Fly,” to the absurdist delight that is “Exit Through the Gift Shop” (the latter became one of my favorite films of all time), I realized that documentaries are not solely academic. They can be art forms in of themselves.

It is a versatile genre — arguably more so than fiction — and different docs use film in differing ways. Some immortalize stories that might otherwise go untold or forgotten, some create intimate moments between subject and audience with people we might otherwise never meet in person. Some capture unique feelings and perspectives to produce empathy, and some, still, fall relatively in line with my initial assumptions. They serve to educate, without too many filmmaking flourishes or surprises to distract from their clear mission.

In my opinion, “Icarus” initially seems to fall into this last category — but as it progresses, and real-life events bleed more invasively into the movie, it undergoes a sort of fascinating metamorphosis. In the beginning, “Icarus” primarily serves to educate us on athlete doping, and it does so masterfully with snappy editing, an excellent score, and interesting subjects to guide us. Our lead, Bryan Fogel, enlists the help of Grigory Rodchenkov, who was at the time head of the Russian anti-doping laboratory. However, Grigory’s accusations of Russia become more vocal as the film progresses, prompting intensifying retaliation from the nation, increasing the stakes for our subjects, and expanding the scale of the movie to one of true crime and government conspiracy. What initially feels like a standard classroom doc (at least, for somebody not inherently interested in either sports or doping) suddenly becomes a larger, darker story.

What stands out to me about “Icarus” is how it appears to adapt, to evolve and to even stumble in real time. As our filmmakers begin to discover that they are working on an international scope and making genuinely dangerous enemies, we can practically feel the pivot. Things that have been emphasized in the first half, such as the races or the original idea of doping Fogel himself, are suddenly dropped in an undeniably clumsy but honest manner. There are massive shifts in focus that I have not experienced in a documentary before, and this is something neither I or the filmmakers themselves saw coming. That in of itself might be worth witnessing.

Nitish:

“Icarus” is an Oscar-winning documentary on the Russian state-sponsored doping program. It focuses on Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov’s revelations regarding the Sochi Olympics, but it touches on a variety of other issues. It’s a slickly produced documentary on an interesting issue, featuring a whistleblower who has spoken out at great personal risk. I think it’s definitely worth your time. That being said, I have two mild criticisms.

I think that the first bit of the movie, where Fogel is trying to gauge the effectiveness of doping by using illicit substances and then going on the Haute route (a grueling seven-day amateur bicycle race in France), is interesting but paced poorly. This issue is accentuated by two points. First, this experiment is not the primary focus of the movie. As such, when Fogel starts explaining details of the Russian Sports Ministry, we’re left a little confused as to why we were watching Fogel bike through France. Second, the experiment achieved a negative result, in that Fogel did not actually improve his time. I applaud his honesty in showing this: good investigations are forthright about their results. But when we spend some 30 minutes on an experiment that has nothing to do with the main focus of the movie, and that experiment doesn’t show what it was intended to, the viewer is left, well, bored. Which is a shame considering the second half of the movie is one of the best documentaries I have seen recently. This first half of the movie should have been cut considerably.

My second criticism is that the movie should have used this space to give more context on the issues that they’re discussing. I would have preferred that they used the time spent on the Haute route instead on discussing the Russian government and its relationship to sports. There is a ton of really interesting material to cover here and I think it would have greatly benefited the documentary to give us greater context here. While “Icarus” definitely covered fascinating material, going a little deeper into things like the FSB, the decisions around the Sochi Olympics, and the IOC’s weak actions regarding the Rio Olympics would have enhanced my viewing experience.

These criticisms notwithstanding, I think “Icarus” is an outstanding example of the power of journalism and art in bringing about change. Fogel and Rodchenkov should be applauded for taking great personal risk in speaking truth to power. Fogel’s relationship with Rodchenkov was arguably what enabled WADA and the IOC to punish Russia for its anti-competitive and illegal practices. “Icarus” would have benefited from a little more time in the editing room, but that should not detract from the extraordinary public service that this documentary provides.

So yeah! Watch it, let us know what you think. I really like documentaries, and I’d love other recommendations that you may have. See you soon!

Contact Mark York at mdyorkjr ‘at’ stanford.edu and Nitish Vaidyanathan at nitishv ‘at’ stanford.edu.