David Starr Jordan was the first president of Stanford University. He was also one of the most influential eugenicists of the early 20th century.

Over the past few months, my Eugenics on the Farm series has dealt with various eugenicists associated with Stanford University and examined their relationship with eugenics, the racist and ableist scientific belief in the improvement of the human race through restricting the reproduction of the “unfit,” typically disabled people and people of color. For Jordan, however, I’m going to do something a bit different.

I’ve written extensively on Jordan’s role in the American Eugenics Movement elsewhere, including in a request to rename Jordan Hall. To summarize, David Starr Jordan founded and worked with many of the most influential eugenic organizations in the United States: the Eugenic Research Organization, the Human Betterment Foundation and the Committee of Eugenics — the first eugenic organization in the United States. He popularized eugenics in talks, textbooks and books for general audiences, such as his 1911 “Hereditary of Richard Roe,” and he promoted the forced sterilization of disabled people. Jordan was the kingpin of early American eugenics, creating networks and organizations deeply influential to the success of eugenic policies in the United States and abroad.

I am not going to write about any of that here. Instead, I am going to focus on Jordan’s complexities, because Jordan was certainly a complex man. He is still often praised for many aspects of his life: his research as an ichthyologist (fish researcher), his activism in various peace movements, etc. However, at the same time, it is impossible to separate his promotion of eugenics from any of these parts of his life. Eugenics was not a mere footnote in Jordan’s life; it was a central aspect.

The piece has a practical point, too. The prominent psychology corner on the right side of the front of Main Quad, one of the first things one sees as they walk up from the Oval, is named after Jordan. When we see that, despite Jordan’s complexities, a central legacy of his has been one of deep harm, it becomes clear why Jordan Hall should be renamed.

Jordan was a passionate anti-war activist. He participated in many anti-war campaigns, such as the World Peace Congress and the World Peace Foundations. Jordan supported other prominent peace campaigns, such as Jane Addams’ Women’s Peace Party and Henry Ford’s Peace Ship. As an anti-war campaigner, Jordan fought adamantly against the participation of the United States in World War I, a position that cost him many friends and earned him many enemies.

While pacifism is certainly a noble position, Jordan’s anti-war beliefs stemmed in large part from eugenic theory. Jordan’s main contribution to eugenic research was on the impact of war on racial health. After studying various historical and contemporary wars, Jordan concluded that war, through the deaths of the brave and survival of the cowardly, reduced the overall ability of the race. In his 1915 book “War and the Breed,” for instance, he wrote that “war involves what real students of this subject call ‘reversed selection’ — in which the best are chosen to be killed, and the worst are preserved to be the fathers of the future.” Jordan’s opposition to war was in the name of eugenics in order to prevent the degradation of the race.

Jordan was also an adamant anti-imperialist and fought against the expansion of the American empire. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American imperialism was on the rise, the most famous example being the Spanish-American War of 1898. During and after the war, the question of turning the Philippines (previously a Spanish colony) into an U.S. colony was on the mind of many Americans. Jordan, though, fought against the expansion of American imperialism and called for the removal of American forces from the island.

His reason was neither benevolence nor belief in the self-determination of indigenous Filipinos, however. Jordan, a believer in the supremacy of white races, simply did not think the inferior Filipino races could comprehend governance. In his 1901 “Imperial Democracy,” Jordan wrote that Filipinos were “as capable of self-government or of any other government as so many monkeys.” Jordan’s racism was the foundation of his anti-imperialist stances.

Jordan donated to and supported a few Black colleges. During his life, he donated a considerable amount to the Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black university founded in part by Booker T. Washington. Jordan was a fan of the institute, though in a rather paternalistic way. In his autobiography, he wrote that he enjoyed the university’s “primative yet delightful negro ‘spirituals.’”

Beneath that support, however, was intense racist reasoning. Jordan’s motivation behind supporting Black universities was his belief in the racial inferiority of Black people. In “The Heredity of Richard Roe,” Jordan argued that citizenship required a “foundation of intelligence” and claimed that Black Americans lacked that foundation. Because of this, he called Black suffrage an “evil.” Jordan thought that Black universities could, if barely, alleviate this dilemma: In a 1910 speech to the London Eugenics Education Society, Jordan lectured that education could help alleviate the “negro problem.” And for Jordan, there was a clear “negro problem”: his textbooks and writings regularly portray Black people as evolutionarily closer to apes than their white peers: “blue gum negroes, blue gum apes,” one read. Despite sending money to a Black university, Jordan only did so based on racist logic, and he actively taught and spread racist ideologies, framing Black people as a problem to be solved.

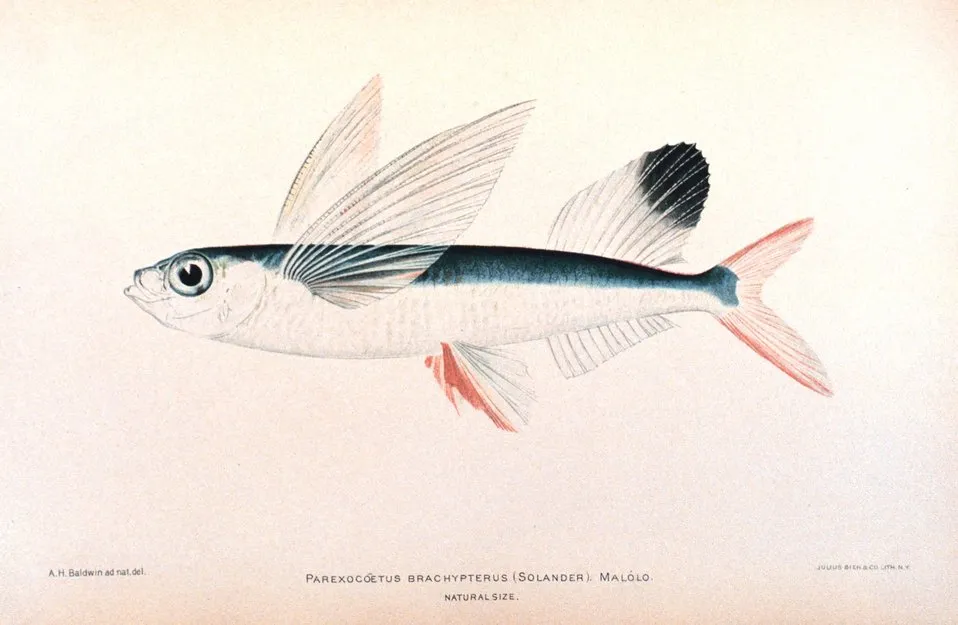

Jordan’s best known academic legacy, besides Stanford, was his research on fish. Many ichthyologists today can trace their academic lineage back to Jordan. Jordan collected fish from across the world, and over 30 fish are named after him. He was especially fascinated with the evolution of fish: his 1923 “A Classification of Fishes” sought to place all fish species on a linear evolutionary line, tracing their evolutionary progression.

Even this, however, is difficult to separate from his eugenic beliefs. Many scientists of this era applied their studies to human eugenics: for instance Luther Burbank, a botanist and acquaintance of Jordan, similarly applied his botanical research to the eugenic breeding of humans. Jordan, too drew connections between his research on fish and eugenics. Jordan’s fascination with fish was a fascination with taxonomies and evolutionary progress: creating categories and sorting fish into them, labeling and studying the qualities of each fish, and tracing the path of evolution. Jordan’s eugenic research was no different: creating eugenic taxonomies of human value, ranking and categorizing human lives, to improve the human race and manufacture evolution. Jordan’s ichthyology research, like that of many scientists of his time, was inseparable from his eugenics research and taxonomization of humans.

In our current moment, we are living in a pandemic that has, in many ways, revealed obfuscated aspects of our society. Again, just as in Jordan’s time, the lives of disabled people are being portrayed as fundamentally less. Again, disabled people are living under the threat of being denied medical care due to their disabilities. Again, certain races are demonized as diseased and unfit. Again, eugenics and its hierarchies of human lives are rearing their ugly heads. Eugenics and the ideologies it perpetuates are being again brought to the forefront in this time of social crisis. It is more important than ever to reject eugenics and to bring attention to its harmful history.

Jordan was clearly a complex man with complex beliefs. Like I wrote in the introduction to this series, I do not believe it is useful to rashly judge figures such as Jordan and paint them in simple strokes.This pandemic, among other things, has shown that eugenics is not a mere historical artefact — it is something to be actively confronted. Jordan’s eugenicist and racist ideologies undeniably permeated through all of his work in ways both obvious and subtle. If the role of the historian is to learn from the past (and it certainly is), historians must also judge the past and recognize the harmful influences of such ideologies. That starts by renaming Jordan Hall, by recognizing that Jordan’s legacy is that of deep harm. And there is nothing complex about that.

Contact Ben Maldonado at bmaldona ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to [email protected] and op-ed submissions to [email protected].

Follow The Daily on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.