The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the importance of adequate preparation and response mechanisms for a global health crisis. It should do likewise for our economic autonomy, particularly as it concerns trade relations with China.

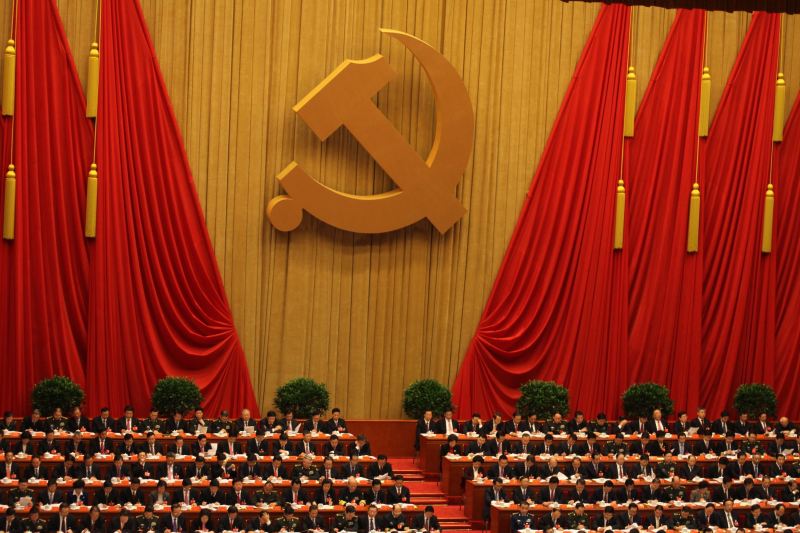

The recent surge in advocacy for a trade reformation is primarily fueled by an intuitive judgment of China’s political ideology and policy implementation standards. This is most fundamentally observed in the increasing mentions of the phrase “Communist China” as the viral contagion has spread. Such a phrase would have seemed fairly novel just a couple of years ago in political circles.

China’s communication with health organizations was unreliable due to censorship, a trademark of communist regimes. This affected other nations’ response times and exacerbated the spread of the virus. China’s pre-outbreak handling of the virus was so characteristically communist that it dilutes its reliability and trustworthiness as a global partner, and by extension the feasibility of transactions with China involving complex products. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) lack of concern for global health suggests that the U.S. should limit Chinese imports of products that sustain the health of Americans.

We have witnessed disturbing applause for the CCP’s post-outbreak handling of the virus (i.e. when the virus became internationally prevalent). These compliments are akin to lauding the Soviet Union for its progress in cleaning Chernobyl’s radioactive waste. Such apologetics must remember that China’s response was made possible by the selfish interest that made the preventative strategy a failure. Ultimately, there is scant evidence to support the CCP’s concern for the broader global community pre-outbreak.

Underlying intentions

People must understand communism as a culture and ideology to approximate the true motives and character of the CCP.

Communism flies in the face of all historical understanding, beginning with the premise that each societal epoch is the product of class struggle, in which the victorious hegemony constructs institutions and culture solely to protect the interests of those who own the means of production. Thus, every such institution deserves ruination because they are leveraged to sustain oppression against the working class. What remains is the dictatorship of the proletariat. Engels elucidated this fallacious reasoning in his “Anti-Dühring“: “all moral theories have been hitherto the product…of the economic conditions of society obtaining at the time…. [M]orality has always been class morality; it has either justified the domination and the interests of the ruling class, or ever since the oppressed class became powerful enough, it has represented its indignation against this domination and the future interests of the oppressed….But we have not yet passed beyond class morality.”

A fundamental aspiration of Chinese communists, like their Russian predecessors, is to establish an international order, which to the logical democratic citizen is a dystopia. In fact, a timetable of world conquest was developed by Chairman Mao Zedong, and can be found on page 5708 of the Congressional Record of April 29, 1954. The plan discusses eventual control over Asia, Africa, Europe and America, in that order. We have yet to see a public condemnation of this plan by the current administration, which is relevant given that the CCP still endorses Mao Zedong Thought.

Aware that their militant power is limited and could never produce a swift victory, modern Chinese communists rely on peaceful coexistence to gradually establish their global footholds. The 13th point of Xi Jinping Thought alludes to this:

“The dream of the Chinese people is closely connected with the dreams of other peoples of the world. Realising the Chinese dream is inseparable from a peaceful international environment and a stable international order. [We must] always be the builder of world peace, the contributor to global development and the defender of the international order.”

The international order has not yet come to fruition; thus, to be its “defender” is to attempt to hasten its conception. It is no surprise, then, that Xi Jinping Thought was described by party colleagues to be a fundamental continuation of Marxism and Mao Zedong Thought. Recent actions that align with point 13 are China’s growing influence on the WHO, its increasing oversight in the United Nations, its mining operations in Southern Africa, its brinkmanship with Hong Kong and Taiwan — and its exploitation of this pandemic to increase nations’ reliance on their manufacturing.

A Precautionary Measure

The threat of the CCP is made less palpable by China’s astonishing GDP and market dynamism. However, we should not conflate material affluence with economic and diplomatic sincerity. That China’s government is the modern purveyor of an amoral political philosophy relays the necessity of decreasing our reliance on its technologies. We should focus trade reform on health products that can be classified as within emerging industries, the domestication of which would not severely raise prices due to their relative novelty and low import level. As MIT economist David Autor explains, “The China shock on large-scale manufacturing…is largely behind us…I think we should be girding ourselves for the real challenge, which is struggles over intellectual property and frontier industries.”

A timely strategy concerns limiting imports of sensitive biomaterials and medicinal necessities. In 2018, the U.S. imported a record $539 billion in goods from China. Yet, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, biotechnology and advanced materials (semiconductors, biomaterials, nanoengineered materials, etc.) imports accounted for less than 0.13% of this capital inflow. Given that these industries carry voluminous potential and represent a modest portion of total imports, their gradual domestication would prove beneficial for healthcare quality assurance and exact a manageable transitional burden on the U.S. economy.

Furthermore, now is the time to redesign U.S. admittance of China’s basic drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients (API’s). A troubling report issued last year by the USCC states:

“Nurtured by subsidies and protected from foreign competition, China’s pharmaceutical companies have emerged as preeminent manufacturers of pharmaceuticals and their ingredients. This presents a direct threat to U.S. economic competitiveness and national security in a number of ways. First, China’s lax regulations put every U.S. consumer taking medicine imported from China, or made with Chinese APIs, at risk. Over the past decade, the U.S. market has been rocked by high-profile recalls of Chinese drug products, such as the FDA’s recall of contaminated heparin, a blood thinner commonly used in U.S. hospitals, which has been linked to 246 deaths in the United States. The 2018 valsartan recall serves as another cautionary tale with global implications, considering the widespread use of the drug. As China’s health market continues to grow, bolstering Chinese regulatory capacity will become ever more critical in order to address poor manufacturing practices and the production and export of illicit drugs.”

The primary tradeoff of targeted reform is increased consumer safety versus a temporary shortage of staple drugs, as China accounts for 13.4% of U.S. drug imports. Economically, however, decreased consumer safety from the status quo is arguably worse, since substandard supply in abundance may lead to fewer consumer expenditures (as faith in overall quality declines). Subsidies and export incentives for U.S. firms would limit our reliance on China’s healthcare market, which is ultimately at the behest of the CCP. This will provide security for the American public and ease the risks of reliance on Chinese imports during future health pandemics — risks of which countries such as Slovakia and Spain are now painfully aware.

There is no doubt the Chinese people are industrious and peace-seeking with a propensity for goodwill. The CCP, however, does not fit this mold, and its influence on China’s production and data-sharing standards — highlighted during this pandemic — merits a domestication of valuable medical technology products and drugs. Historical and philosophical logic commands discretion in relations with communist regimes, and our transactions with China unfortunately illustrate a lessening degree of vigilance. Following the COVID-19 upheaval, the U.S. can make slight amends through gradual protectionism concerning industries — both emerging and long-established — that cannot be left to the devices of the CCP lest we compromise the health of Americans.

Contact Jeeven Larson at jlarson7 ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to [email protected] and op-ed submissions to [email protected].