Stanford Law School (SLS) professor emerita Barbara Allen Babcock — a legal trailblazer in gender equity and the first female tenured faculty member at the law school — died of breast cancer on April 18 at her home in Stanford, California. She was 81.

Babcock, who Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg credits with her first judicial appointment, worked at Stanford for nearly 30 years, teaching and writing in the fields of civil and criminal procedure. Her colleagues describe her as a passionate advocate who paved the path for women in law.

“Barbara Babcock was a force of nature–a great trial lawyer who became an influential scholar and a mentor to generations of lawyers,” wrote law professor Pamela Karlan in an email to The Daily. “What set her apart from many of her equally brilliant colleagues was her generosity of spirit and real-world savvy. Her sayings in class were legendary for their wit as well as their pointedness.”

“She brought in a feminist sensibility and she had a huge influence on the law school — a huge influence at every level,” said retired district court judge and former SLS dean of minority admissions Thelton Henderson in a Stanford Lawyer tribute. “There must be hundreds of women lawyers out there that she inspired and sent out into the world and made them feel whole.”

Babcock is survived by her husband, emeritus law school professor Thomas Grey; her stepdaughter, Rebecca Grey; and her brothers David Henry Babcock and Joseph Starr Babcock.

Ginsburg said, ‘I would not hold the good job I have today if it were not for Barbara’

Babcock was born in Washington in 1938, the daughter of a homemaker and lawyer. She grew up in Hyattsville, Maryland, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1960.

After going on to study at Yale Law School — one of 13 women in a class of 175 — Babcock clerked for Judge Henry W. Edgerton on the D.C. Court of Appeals and became an associate at Williams & Connolly, a prominent criminal defense firm.

“Her extraordinary empathy, especially for those in distress, led her to advocate a particular view of the role of criminal defense lawyers — as uniquely positioned to provide people who have often had few forceful advocates or friends in their lives a true devoted champion,” SLS professor Mark Kelman told The Daily. “But it also led her to help build one of the strongest public defender offices in the nation and to nourish extraordinary relationships with her clients.”

Babcock was particularly passionate about socioeconomic equity in legal representation. In 1966, she joined a pilot project at the Legal Aid Agency for the District of Columbia (D.C.) that developed into Washington’s Public Defender Service in 1968, providing legal services for D.C.’s low-income communities. Babcock was named the service’s first director.

“Barbara was a great mentor to the attorneys at the Washington D.C. Public Defender Service,” wrote SLS professor Michael Wald in an email to The Daily.

Wald worked as an attorney at the D.C. Public Defender Service (PDS) when Babcock was the Director and helped recruit her to Stanford.

“Barbara was able to combine precision and toughness with warmth and humor in a unique way that made her a great trial lawyer and also a loved leader of organizations,” Wald added. “She built PDS into the best public defender office in the country.”

While running the D.C. services, Babcock was also invited to design and teach a new class at Georgetown called “Women and the Law,” one of the first legal courses focused on women’s issues in the country. In the 1960s, there were very few women law professors, and she quickly became part of a tight-knit community of academics.

“We didn’t set out to be feminists, much less feminist law professors,” Babcock said in a 2018 speech at the New York City Bar Association. “Rather we fell into it, or we were pushed into it by our students, who wanted courses on women and the law.”

In the late 1970s, President Jimmy Carter appointed Babcock to head the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Division. There, she met former SLS dean Thomas Ehrlich, who was the director of the International Development Cooperation Agency under Carter.

“She brought to that position, as to everything she did, a profound commitment to justice, and an eagerness to do everything she could to bring justice particularly to those who lived in poverty,” Ehrlich wrote in a statement to The Daily.

Babcock was passionate about representation in law, and she spent her time at the Justice Department lobbying for the appointment of more women and minorities on federal circuits. By the end of President Carter’s term, he had appointed more female and minority judges than all previous presidents combined. One of those women was Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who credits Babcock for her appointment.

“I would not hold the good job I have today were it not for Barbara,” Ginsburg said at the same 2018 bar association event.

Babcock joins Stanford

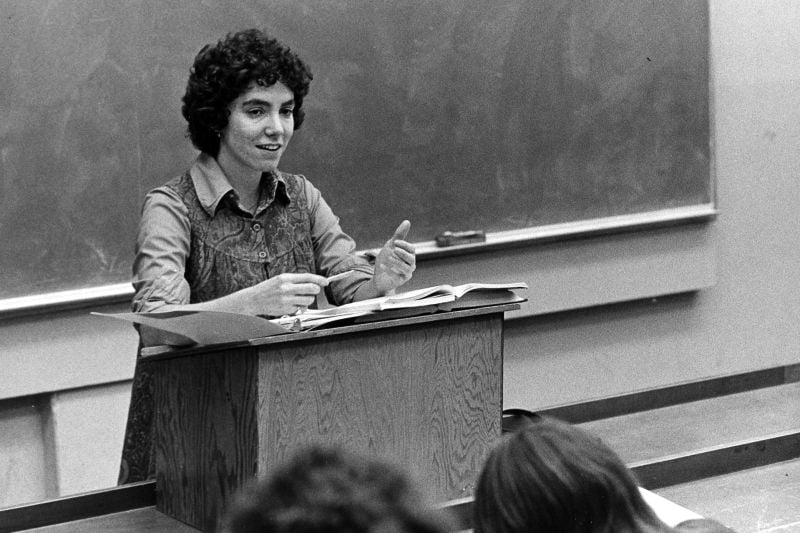

In 1972, Babock was recruited to work at SLS, where she taught for more than 30 years. She received the John Bingham Hurlbut Award for excellence in teaching four times. Babcock became the first woman to hold an endowed chair at SLS and the first woman to receive emeritus status in 2004.

Ehrlich said that Babcock joined the SLS faculty amid political “turbulence” due to protests against the Vietnam War and movements for equality and justice. Along with the students, Ehrlich said, the faculty was changing, and Babcock was an integral part of the evolution.

“Barbara was one of the first faculty members chosen when I was dean,” Ehrlich said. “I knew that anyone hired as the first woman in an all-male faculty would have challenges. But I also knew from Barbara’s work as the first director of the Public Defender Service of the District of Columbia that she was a trailblazer.”

SLS professor Lawrence Friedman echoed those sentiments.

“It’s hard today for both men and women to imagine what it was like in the days when there were few women lawyers, judges, and law professors and even harder to imagine what it was like to be one of those few women lawyers, judges, and law professors,” Friedman said. “You had to be somebody very special. And if you had to pick one word to describe Barbara Babcock, that’s the word: special. A special lawyer, a special teacher, a special scholar.”

In her time at Stanford, Babcock taught several pivotal courses, including Criminal Procedure, Criminal Law and Civil Procedure.

“Anyone who had Civ Pro with Barbara Babcock came to understand within about a week that it would be unlike any other mandatory 1L course, and possibly unlike anything else we would do at law school,” wrote Dahlia Lithwick JD ’96 in the SLS Tribute. “Under cover of teaching us dry rules of procedure, Babcock was putting on a clinic about civil justice, racial equality, poverty, and the importance of lawyers in society.”

“Barbara was an electrifying classroom teacher,” added SLS professor Norman Spaulding J.D. ’97. “At any level of education, no matter how talented the instructors are, it is rare to take a class knowing you are going be on the edge of your seat in every session. But that’s what it was like to take a class with Barbara. Part of it is that she was a marvelous story teller, and having tried many criminal cases to verdict as a public defender, she had seen the law in action. So in addition to being riveting, her stories conveyed something essential about how the law actually works — insights and wisdom not to be found in case reports and standard academic commentary.”

Babcock also leveraged her legal experience to develop hands-on learning experiences for her students through clinical work. She taught her first clinic in the fall of 1974, focusing on sexual discrimination cases.

Nancy Hendry J.D. ’75, senior advisor for the International Association of Women Judges and former general counsel of the Peace Corps, was a student in the class.

“The clinic provided an analytical framework and vocabulary to deal with these big issues that larger society and the law school were dealing with,” Hendry wrote in the SLS Tribute. “Barbara was a big piece of making these issues important and valued.”

In 1982, when Stanford Law piloted The East Palo Alto Community Law Project, a student-initiative and precursor to the current Stanford Community Law Clinic, Babcock was also enlisted as a board member, helping students hone their clinical skills.

‘A woman of extraordinary empathy’

In addition to praising Babcock’s contributions to law and academia, colleagues said that Babcock’s commitment to bringing compassion into every class and conversation set her apart.

SLS professor John Donohue, who taught alongside Babcock for several years, was a close friend of Babcock’s and her doubles partner in tennis.

“She was of course a pioneering woman in law, government, and the legal academy but she was also an outstanding and utterly, beloved teacher and SLS colleague,” Donahue wrote in an email to The Daily.

“She was among the most popular faculty members, and always had time to listen to and talk with students as well as her colleagues,” Ehrlich added.

Donohue said Babcock was also cherished for her honesty and sense of humor.

“She was a warm, humane and exceptionally funny person, who was utterly unafraid to speak her mind,” he wrote. “She was unfailingly and bracingly candid, and quick to lampoon thoughtless political correctness.”

Though deeply involved in teaching and working in clinics, Babcock never abandoned her passion for writing and teaching about women in law. She spent years conducting research on female legal history, and published several notable works. These include “Woman Lawyer: The Trials of Clara Foltz,” a 2011 biography about California’s first woman lawyer, and “Fish, Raincoats: A Woman Lawyer’s Life,” her 2016 memoir.

She also helped found Equal Rights Advocates, a San Francisco-based nonprofit dedicated to women’s rights, where she developed early legal work combatting sex discrimmination at work and school. Her career of legal scholarship earned her The Margaret Brent Women’s Achievement Award, which recognizes and celebrates the accomplishments of female lawyers who have excelled in their field and paved the way to success for other women lawyers, according to the organization’s website.

“Her devotion to the historically excluded — simultaneously fierce and exuberant — led her not only, as an academic, to uncover the histories of the women who broke through barriers to participation in the legal profession but also led her to mentor countless students at Stanford who were often living in the shadows: women, students of color, LGBTQ students,” Kelman wrote. “Her obvious charisma, coupled with a one-on-one authenticity that few charismatics possess, made her beloved by hundreds of students in a way no other professor I’ve known is beloved, even the most gifted ones.”

Contact Sarina Deb at sdeb7 ‘at’ stanford.edu.