NOTE: This is the second in a two-part series discussing the U.S.’s actions toward China in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Read Part 1 here.

Rhetoric as a political tool for China

In his 1983 book, “Imagined Communities,” Benedict Anderson famously states that state media plays an integral role in determining nationalism, allowing the people of a nation to imagine sharing a collective experience, regardless of their position in society or geographical proximity to one another. In our last article, we showed how American leadership has espoused a scathing narrative against China, fomenting violence and stigma against Asians in America. In this article, we will discuss the geopolitical risks resulting from this narrative.

When American leadership lambastes China, the effects are twofold: Not only does this foment nativist nationalism in the U.S., but it also grants Chinese leaders the ability to paint American attacks as an assault on Chinese dignity, legitimizing authoritarian tactics as they attempt to defend their nation.

This is precisely what Beijing has done. According to Susan L. Shirk, chairwoman of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California, San Diego, Chinese state-run media has used the crisis to emphasize the superiority of China and the personal strength of Xi Jinping.

For example, Hu Xijin, a Chinese propagandist and editor of the state-controlled Global Times, recently characterized President Donald Trump’s cathexis on China as an attempt to divert the focus away from his administration’s “incompetence.” This fits within Beijing’s broader attempt to contort the narrative and downplay China’s culpability. Some Chinese leaders have even gone so far as to suggest that the virus originated in America.

More strikingly, China has moved to expel American journalists. It has also mobilized the “internet police” to remove unflattering accounts of the government. This week, the U.S. responded by imposing new visa restrictions on Chinese journalists. Beyond representing a fundamental affront to journalistic freedom, American antagonism has entrenched the ideological control of the Chinese state. Such actions by the Chinese government become justifiable only by virtue of American prejudice; that is, American antagonism justifies increasing authoritarianism and fails to capitalize on the growing number of Chinese citizens who are demanding accountability.

Effect on the global fight against coronavirus

Entrenching ourselves in nationalism only pushes us further from a cure. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), pointing fingers at nations with higher numbers of cases could discourage accurate reporting on domestic outbreaks. It follows that blaming China will make them more hesitant to cooperate too.

In March, United Nations (U.N.) Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called for a global ceasefire, urging nations to settle their differences and prioritize multilateral cooperation. On April 14, however, Trump announced the U.S. would halt funding to the WHO, an agency that Guterres has called the most critical organization in combating the coronavirus.

Trump’s rationale for withdrawing funds was that the WHO initially echoed the Chinese government in claiming that the virus was under control. Despite this, there seems little evidence to suggest that China has attempted to structurally undermine the WHO, nor that it has fundamentally corrupted it. On the contrary, as the largest contributor to the WHO’s operations, America’s health and medical experts play an outsized role in determining the institution’s trajectory.

Despite these challenges, on May 8, it seemed like the world had finally put its differences aside. The U.N. was on the cusp of passing a resolution that embraced Guterres’ call for a global ceasefire, as well as “enhanced coordination” on addressing the pandemic. Given that both the U.S. and China had supported the draft, it looked poised for success. The tone at the U.N. was optimistic, though as Tunisian ambassador Kain Kabtani put it in the days preceding the vote, “It’s a moment of truth for the United Nations and the multilateral system.”

In a shocking reversal, the U.S. vetoed the resolution — merely because it mentioned the WHO. China insisted that it contain reference to the WHO; the U.S. refused to accept this; and so, against the backdrop of 275,000 global deaths, this necessary and unifying plea has failed.

This is clearly not an issue just about the WHO; rather, it is indicative of the extent to which tensions have escalated. According to a diplomat at the U.N. Security Council, with this rejection, “We are back to square one.” Months of progress and thousands of lives have been wasted. Geopolitics has degenerated into immature quibbling over the minutiae, and the constant name-calling and scapegoating are at least partially to blame. Time is running out: American politicians must end this vehement rhetoric before it is too late.

However valid any of these concerns about China or the global order are, the midst of a pandemic is not the time to raise them. As the U.N. vote has shown, this myopia directly impedes any multilateral attempts to combat the virus, selfishly endangering lives not only within the U.S., but also abroad. Succumbing to such intransigence sets a terrible precedent for future diplomatic relations and seriously damages confidence in American leadership throughout the international system.

While the governments of the two largest economies are butting heads, the science communities across the Pacific have done a great deal to facilitate the transfer of data for the sake of better understanding the virus and therefore accelerating the development of a potential vaccine. Ironically, one of the key collaborative hubs for COVID-19 research has been the WHO.

This is precisely why many scientists are worried that political tensions will create irrevocable blockades and worsen the timestamp on the development of a vaccine.

Creating opportunity amidst crisis

As former U.S. ambassador to Russia and current Freeman Spogli Institute (FSI) Director Michael McFaul put it in a recent Washington Post op-ed, “Framing Chinese and U.S. international efforts in response to the coronavirus in zero-sum terms is counterproductive.” This is absolutely correct. The idea that the U.S. can blame China into responding to COVID-19 better is a jingoistic fantasy that precludes the possibility for any meaningful cooperation. Even if our politicians are correct in their diatribe — that is, China really is to blame — now is not the right time to attack.

Instead, our leaders should recognize Chinese efforts to combat the virus — and make good faith attempts to support them — while condemning the racist language and sentiments currently spreading.

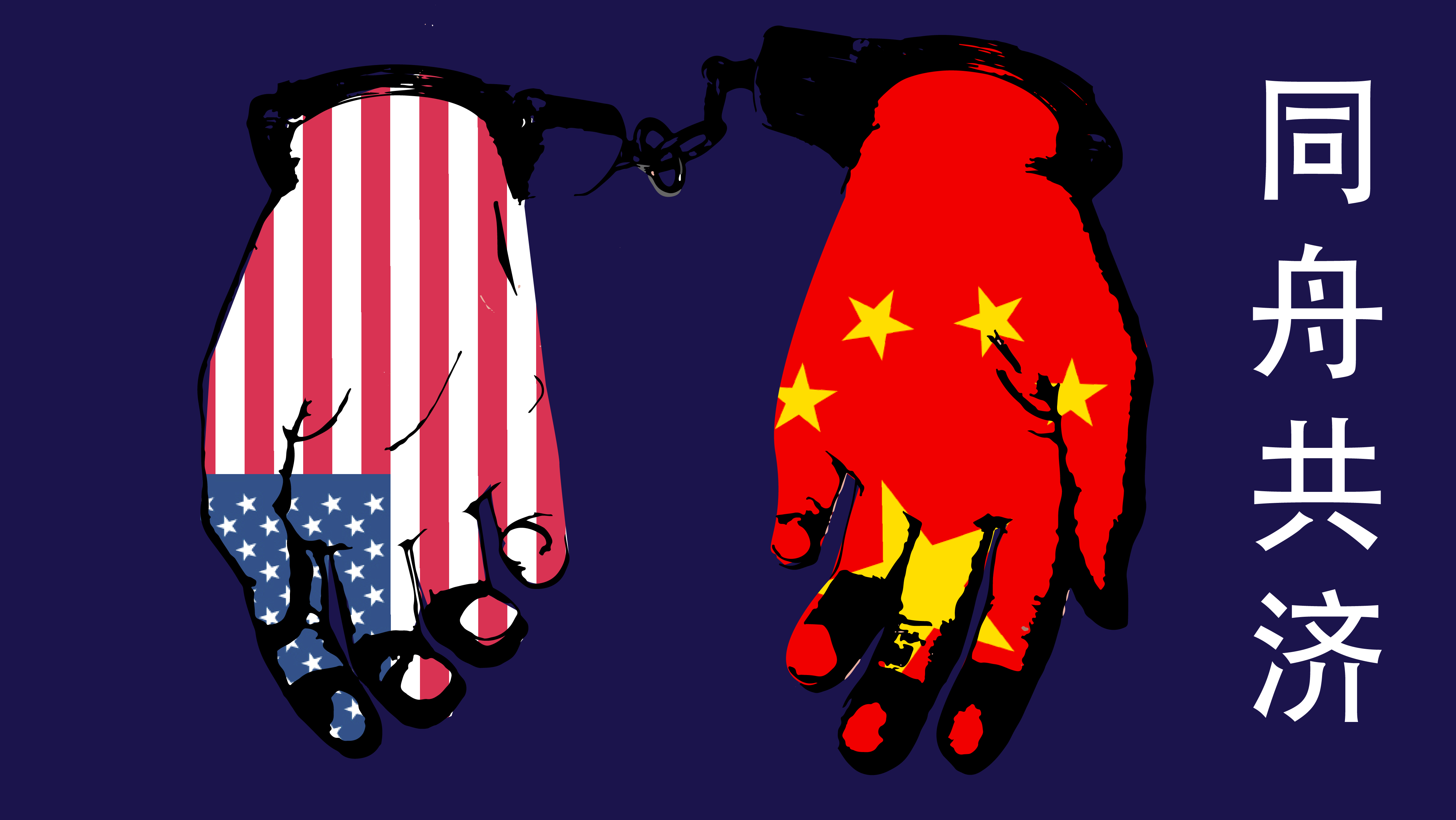

Ameliorating tensions won’t be easy; even compromising on small details now seems an unthinkable geopolitical concession. But insofar as U.S.-China animosity is reciprocal, compromise could garner an enormous payout by setting the stage for future cooperation.

COVID-19 represents a real opportunity for unity. After all, this issue is not a politically realistic one; it is not zero-sum. As previous global crises have shown, international cooperation mutually benefits everyone involved, as countries are able to pool resources and knowledge. In 2008, amid the market crash, the G20 rallied together to help bring the global economy back on its feet, according to former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. After 9/11, global cooperation was similarly galvanized. As McFaul noted, quoting Siegfried Hecker, even the U.S. and the Soviet Union were “doomed to cooperate” on nuclear issues after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Indeed, the issues that previously mired U.S.-China relations, like contention in the South China Sea, the future of Hong Kong and the trade war, have faded from the limelight. Now is the time for the U.S. and China to band together, to unite to lead the global effort against the COVID-19 pandemic. But to do that, the name-calling and scapegoating must end. Neglecting to do so will only ramp up the danger, while stymying any hope for opportunity.

Contact Michael Alisky at malisky ‘at’ stanford.edu and Daniel Gao at dgao ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to [email protected] and op-ed submissions to [email protected].Follow The Daily on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.