Lately, there’s been much buzz in the news about an unorthodox way of finding a vaccine for COVID-19: human challenge trials. Whereas plenty of articles have debated whether human challenge trials should be legal, this article focuses on whether we have a moral duty to participate in them. The goal here isn’t to single-handedly answer this complex moral question, but rather to provide two frameworks we can use to help us arrive at our own answers.

What exactly is a human challenge trial? In short, it’s an alternative way of approaching Phase 3 — the human trial stage — in a vaccine’s approval process. A regular human trial entails vaccinating some participants, but not others. Then, all participants would more or less go about their daily lives. If someone happens to contract the disease, the effects of the vaccine can be observed. If not, then we don’t learn anything new. As you can imagine, the usual way of approving a vaccine takes months to years.

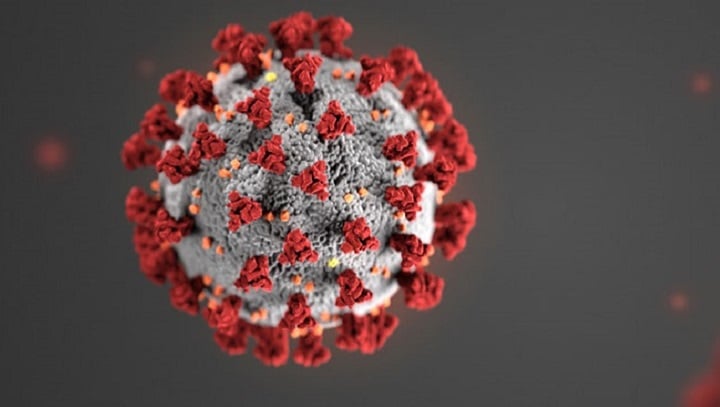

On the other hand, a human challenge trial means directly injecting coronavirus into a small group of human participants. This way, we are guaranteed to find the effectiveness of potential vaccines. It would very likely speed things up. In fact, it’s been argued that because human challenge trials will help us find a COVID-19 vaccine much faster, tens of thousands of lives will be saved.

Only vaccines that have passed Phase 1 and Phase 2 would be considered for a human challenge trial, but it’s still a lot riskier than the norm. Instead of letting COVID-19 play out its game of chance (as in the original process), volunteers for a human challenge trial are guaranteed to be infected.

And yet, momentum is spreading across the nation in support for human challenge trials — even from some ethicists and the World Health Organization. Thousands of people have expressed interest in volunteering. There is also precedent for the FDA approving human challenge trials. It’s possible that we, as mostly young and healthy individuals — with the lowest risk of COVID-19-related death — may soon be presented with the opportunity to be infected with COVID-19 for the sake of developing a vaccine that could save many, many lives.

Moral Duties

Here’s the question I’d like to address: Suppose that human challenge trials are approved. Are we morally obligated to participate?

I’ll start with some clarifications. First, let’s assume that human challenge trials will indeed shorten the time until a vaccine is found and that the projections of lives saved is roughly correct. Second, let’s assume that the particular young and healthy individual in question is in a position to commit to a clinical trial. For example, the individual we’re thinking about is not the primary breadwinner for a family, a caretaker for elderly people, etc.

I also want to note that anyone who volunteers is undertaking a tremendously generous act of public service and should be considered a hero. The question at hand is not simply whether it is a good thing to volunteer for a human challenge trial (the answer to this is a resounding yes, I think), but rather whether it would be morally wrong for us to not participate, as long as a vaccine has not yet been found.

Here’s a way to think about moral duties. We, as individuals, each have our own liberty — a basic right to choose how we want to go about living our lives. We ultimately reserve the right to decide whether we want to participate in a trial. A moral obligation to participate, then, implies participating even if we do not want to. Moral duties override our basic liberty in this way. For a moral obligation to exist, then, there should be compelling enough reason to believe that overriding someone’s freedom of choice is justified.

In this article, I present just two potential reasons why there might be a moral obligation to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine human challenge trial. Whether these reasons are strong enough to form a moral duty to participate, however, is ultimately up to each individual to decide.

The Utilitarian Reason

First, let’s consider our situation in terms of its benefits and harms. I’ll call this reason the Utilitarian Reason. The Utilitarian Reason holds that as long as more benefits than harms are produced by an action, we morally ought to do that action. Following this line of reason, the benefits of an earlier vaccine are immense and, as we assumed earlier, at least tens of thousands of lives would be saved. Furthermore, the relative harm from COVID-19 for us as young and healthy individuals is comparatively small. (Let’s assume it’s small, at least. It may not be true in reality.)

In some cases, such as for those of us who live in areas with high exposure to COVID-19, the harm from COVID-19 is somewhat inevitable. Hence, the additional harm done by participating in a human challenge trial would be minimal. Clearly, the benefits outweigh the harms by a huge factor. If we only care about how our actions affect the net benefits to society — which is true for the Utilitarian Reason — we morally ought to participate.

To a certain extent, the Utilitarian Reason is compelling. Consider Peter Singer’s familiar example: We walk by a pond, and a child is drowning. Most people would agree that we ought to go and save the child’s life; the cost is, at most, getting your clothes dirty. Why shouldn’t we generally help others when the cost to ourselves is relatively small? Surely, being injected with a virus that will most likely not cause a full-blown illness for most young and healthy people is worth the lives of tens of thousands of people. People who have already expressed interest in volunteering for a human challenge trial cited a similar reason for doing so: The harm to them is relatively small, but many lives could be saved.

But the logic of generally helping others whenever the cost is comparatively small can also make the Utilitarian Reason less compelling to some. It assumes two things: First, that distance does not impact moral duty. You have just as much of a moral duty to save a child drowning in front of you as a child across the globe. This means that buying your mom those flowers for Mother’s Day instead of donating it to charity was probably the morally wrong thing to do. The Utilitarian Reason is a standard that can be very high to live up to: You have a moral obligation to help regardless of who you are helping.

Furthermore, the Utilitarian Reason does not care who, exactly, is making the sacrifice. It’s happy as long as someone does it. An outcome where one lonely individual is donating most of their savings to charity is just as good as an outcome where the government coordinates a tiny percent of everyone’s savings to donate to charity. For two outcomes to be equal, all that matters is the total amount donated to charity. So, for the average Joe who comes along and sees that no one is donating to charity, the Utilitarian Reason would require Joe to donate even more than he would have had everyone been donating to charity. He’d have to make up for the negligence of non-donors. That can also seem like somewhat of a tall order that Joe might balk at.

The Fairness Reason

Let’s now consider a more modest reason to be morally obligated to participate in human challenge trials. I’ll call this the Fairness Reason. I think that someone who is not convinced by the Utilitarian Reason — after all, not all of us are willing to give up Mother’s Day flowers so readily — could potentially be convinced by the Fairness Reason.

Instead of just caring about what would be beneficial, the Fairness Reason factors in who is contributing the benefits, and for whom. The Fairness Reason holds that we have a moral obligation to contribute our fair share within our local community. We don’t have to worry about helping the entire world, and we don’t have to strive to be a saint. Whereas the Utilitarian Reason dictates that a moral obligation always exists to participate in the challenge trial because the benefits outweigh the harms, the Fairness Reason says: It depends. We only have a moral obligation to participate in the trial if we haven’t already done our fair share, and if our participation is an essential benefit to people in our local community. Let’s investigate both of these components.

First, the Fairness Reason requires us to contribute our fair share. What does “fair” mean? We won’t try to give a complete answer here. Compared to the Utilitarian Reason’s relatively numerical cost-benefit analysis, the Fairness Reason leaves room for ambiguity. But, let’s consider the following example: When we’re at war, in an ideal world, everyone who has the ability to fight has an equal chance of being drafted into the military; that’s contributing their fair share. It would be unjust if some able-bodied people were arbitrarily forced to risk their lives with higher probability than other able-bodied people.

How does this apply to COVID-19? Imagine COVID-19 as an enemy we’re at war with. It’s certainly been described as such. So far, a group of people has already been forced to risk their lives in this war, daily. These are the people whose jobs have been deemed “essential.” Consider the man standing at the cash register at your local Safeway. Or the woman working at the meatpacking plant who can’t afford to skip work, even though conditions are extremely risky. Hospital workers certainly did not sign up to save lives without basic protective personal equipment. These are people drafted to the war, many unarmed.

Furthermore, these are people carrying far more than their fair share of risk towards defeating COVID-19. Being a cashier versus a software engineer does not impart moral significance; there is no moral law that requires cashiers to risk their lives to keep society functioning, while absolving software engineers of any duty to pitch in. For those of us who aren’t “essential” workers, the human challenge trial presents an opportunity to shoulder our fair share of risk for the common good. If we find the Fairness Reason compelling, then, there would be a moral obligation to take on our fair portion of risk and participate.

Second, the Fairness Reason applies to our local community. It doesn’t require us to think beyond our own society, or even neighborhood. But there is hardly a huge distance involved in COVID-19. Plenty of us know others who have been affected. These are our own lives that we’re talking about.

That’s why the Fairness Reason can be somewhat more convincing than the Utilitarian Reason: We don’t have to believe in a cold calculation of harm weighed against benefit to find that a moral duty to participate in human challenge trials exists. The average Joe who doesn’t just think about what is good, but who cares more about the people close to him than those across the globe and isn’t so willing to do more than his fair share, could be convinced.

How should we interpret this, though? Would it be a good thing for us to participate in a human challenge trial? Yes. It would be nice. It would be beneficial. Of course an earlier vaccine would be appreciated. But, would it be morally wrong not to be injected with coronavirus in order to expedite the vaccine-search process? That’s up to us to decide by figuring out whether we’re convinced that such a moral duty to participate exists. After all, at stake is our personal liberty — which is undoubtedly also important.

Special thanks to professor Jorah Dannenberg for the helpful feedback.

Contact Marilyn Zhang at zmarilyn ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to [email protected] and op-ed submissions to [email protected].

Follow The Daily on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.