Note: Some sources were granted anonymity due to fear of retaliation by the University given the possibility of upcoming cuts

The University has put forth a policy providing additional job security to tenure-track faculty during the COVID-19 crisis. But lecturers have been left out of such policy changes, not just at Stanford but at other top schools around the country such as Yale and Harvard.

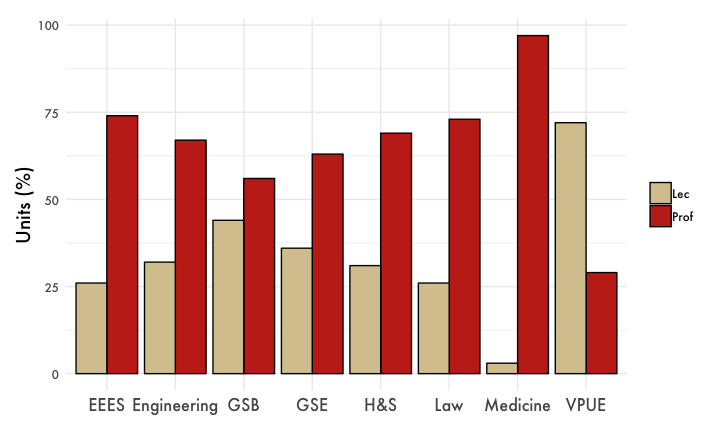

The 2018 Provost’s Committee on Lecturers found that 27% of all academic units for the academic year 2016-17 were taught by lecturers. Lecturers were found to be especially key to first-year programs like the Program in Writing and Rhetoric (PWR) and Thinking Matters; 70% of units offered by the Office of the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education (VPUE) were taught by lecturers. They also formed a significant part of the theater and performance studies, music, English and foreign language departments.

Even without a pandemic, lecturers face unique constraints. They are not eligible to be on the Faculty Senate or Academic Council, leaving them without direct representation in that body. What’s more, lecturers’ job security “at any time depends on how committed our own academic units are to keeping us, and how committed the Provost is for funding our appointments,” PWR lecturer Ruth Starkman told The Daily.

Now, during the pandemic, lecturers expressed concern about budget cuts under consideration. A university-wide hiring pause and salary freeze has already been implemented, applied uniformly to both lecturers and Academic Council faculty. However, multiple lecturers worried about the impact budget cuts might have on lecturers, saying that lecturer salaries are often already below the local cost-of-living.

Multiple lecturers were granted anonymity due to fear of retaliation by the University given the possibility of upcoming cuts.

“Usually my salary goes up a little bit each year with inflation,” said one lecturer. “I can imagine that for a lot of lecturers, not having this small increase (of a thousand dollars or so per year) would be very impactful, considering how expensive it is to live in the Bay Area and the financially precarious position many junior academics can be in.”

The sources of lecturer salaries vary depending on what school they teach in, according to University spokesperson E.J. Miranda. These salaries are funded by both general funds and Stanford’s endowment, but “lecturer salaries can also come from different funds,” Miranda wrote in a statement to The Daily.

Miranda declined to comment on specific criticisms posed by lecturers in this article.

Multiple lecturers hypothesized that the hiring pause may mean existing lecturers need to take on more units than they usually teach, but without the supplementary income to go along with it.

Monetary concerns aside, many expressed a general feeling of job insecurity. The special term extensions that have been put in place for some tenure-track faculty do not apply to lecturers.

“Universities across the country are seeing reduced enrollments, greatly reduced income, reduced endowment returns, etc. and all of this is going to prompt cost-cutting measures,” another lecturer said. “I worry about being a non-tenured staff member at Stanford because my employment is explicitly linked to enrollments and program needs.”

A PWR lecturer said she feels like all instructors at Stanford without tenure are worried right now. She added that she is in the middle of her contract, but that she said that the contract specifies that “appointment is subject to early termination at any time based upon unsatisfactory performance or for programmatic reasons (including budgetary considerations).” This inclusion of budgetary constraints as a possible reason for early termination worried her.

Political science lecturer Brian Coyne said Stanford leadership is aware of these issues and recognizes the increasingly large role lecturers play in teaching throughout the University.

“Even before the current crisis, there’s been an effort to even out some of the discrepancies across departments and discussions of ways to give lecturers improved job security,” Coyne said.

Lecturers appreciated the measures Stanford has taken in order to improve their ability to teach and thrive this quarter.

“The number of training sessions, training courses, town halls, emails and office hours that they have offered is really impressive,” said another lecturer. “I am also receiving a monthly stipend to offset the cost of my internet bill, which I take as recognition of the requirement for us to have this utility in order to perform our duties.”

The PWR lecturer who requested anonymity said she was glad to see VPUE support her colleagues who, for childcare or other needs, needed work accommodations. She added that she has been allowed to spend professional development funds on some technology that normally would be excluded. But she also expressed concern about the future of such funds and that budget cuts could lead to taking away the resources that underfunded programs have fought for over the years.

“I think that to support lecturers under the pandemic they should support lecturers generally: raise our salaries to be commensurate with cost of living […] and shift us out of precarity by creating a Teaching Professor track that institutionalizes and puts money behind the work of teaching undergraduates,” she said.

She added that she would appreciate a vocal commitment to retain all current lecturers and extend all contracts by one year as is being done by some other schools.

Another lecturer said he could think of further measures the University could take to support lecturers, but was unsure whether any of them were reasonable or sustainable.

“It would be nice to have some fiscal support to set up a home office (my computer is literally in my closet, so I pull up against the desk and shut the closet doors behind me when I’m teaching or in meetings),” he said. “But is this fair to those who already have dedicated office space or to those who live in expensive markets? […] I can’t see Stanford footing the bill to buy us all ergonomic office chairs for our personal homes.”

He added that he would like quicker decision-making from Stanford, but understands that the reason things are on hold is because of uncertainty.

“I don’t want them making decisions that they have to retract later (or worse: that jeopardize the health of Stanford folks!), so I’m learning and re-learning patience this quarter,” he wrote.

Most lecturers agreed that while there are issues that needed to be addressed, Stanford is aware of this problem and has the power to handle it well.

“Being on the bottom of the non-tenure track hierarchy, whether at a university with a union or not, is always precarious,” Starkman said. “Let’s hope the university does the right thing. They know some of their best, prize-winning teachers are non-tenure track.”

Contact Smiti Mittal at smiti06 ‘at’ stanford.edu.