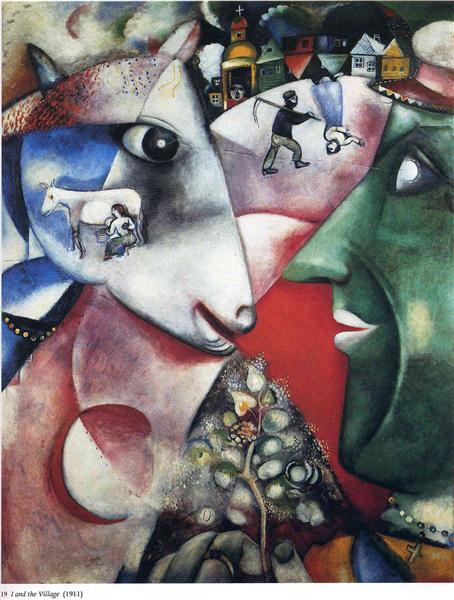

A few years ago while visiting the MoMA, I encountered a painting titled “I and the Village” by Marc Chagall. What I found fascinating about the piece was the lack of negative space; scanning the massive canvas, my eyes skipped from one overlapping scene to the next, swimming in swathes of color and never knowing where to settle.

At Stanford, life often feels this way. There is a constant stream of people to meet and events to attend, and little space to breathe. I am whelmed by the presence of people, classes, p-sets; any negative space is easily ignored.

Since March, though, milestones have felt distinctly marked by absence. My sister recently graduated from her master’s program with an online ceremony, an occasion marked more by the absence of an in-person celebration than the presence of a newly-earned diploma. My days have been filled with negative space, and I have spent many hours ruminating over the quarter I expected to have in D.C. and sitting alone with my thoughts.

Last week, I attended a memorial service for a close friend’s parent who had recently passed away. This was someone I had not seen for several months, and their passing didn’t feel truly tangible until the service. Even in a life newly filled with negative space, I found it hard to conceptualize the loss until this moment, a small event made even more solemn by the face masks worn by nearly everyone in attendance. This time, it was the presence of my friend and her family that made me confront this new absence.

Today, when I revisited “I and the Village,“ what I noticed wasn’t the lack of negative space, it was that the negative space of one scene also served as the positive space of another. A scene of a woman milking a cow is painted on top of the face of a goat, which sits in front of a path leading to a village. In this case, examining the goat’s role as negative space is just as important as recognizing its role as a primary subject.

Recently, I have been returning to the negative space I previously ignored at Stanford; in engaging with things I used to push to the background, I have reconnected with friends from home who I had been reticent to reach out to, reengaged with hobbies I left behind in high school and reassessed broad questions of my values that I found easy to dismiss while at school. At the same time, I have learned to feel more gratitude for the positive space that I was able to experience on campus and now at home.

The Stanford experience creates a mental film that makes it easy for us to ignore things in the background. It’s a mindset many students learn to become comfortable with — inevitably, pset partners flow in and out of our lives with every quarter; friendships strengthen and ebb depending on the proximity of residence; commitments to student organizations become malleable as new opportunities and priorities arise. This quarter has taught us that we delude ourselves when we only fixate on the new and present without actively engaging with the things we are leaving behind — positive space cannot exist without negative space.

Contact Lena Han at lahan ‘at’ stanford.edu.