On May 25, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was filmed killing unarmed Black man George Floyd. Chauvin has since been charged with manslaughter and murder, but the death of yet another Black American at the hands of a white police officer has fueled public outrage as protesters demonstrate in major cities across the country against police brutality.

I have spent the weekend reading about the protests in Columbus, Ohio, and speaking with demonstrators, as well as attending a protest myself on Sunday. The following is a summary of what has happened so far as well as a personal account of what I saw.

Before I go any further, I want to say that while I recognize the property damage caused by some demonstrations, I’ve made the choice in this article not to use the term “riot.” So in order to avoid the violent and racially charged language supported by Trump and the conservative media outlets that inform him, I will use the terms “demonstrations” and “protests.”

As a white woman, I have had few negative interactions with the police here. The few times I’ve been pulled over, the officer has acted as though they were on my side; once when I was 16 I was even let off with a warning after I started crying. But the Columbus Police Department (CPD) has, like many major American city police departments, a history of racism, violence and abuse. In 2016, 13-year-old Tyre King was shot and killed by police when one mistook his BB gun for a pistol. In 2018, a Black Columbus police officer sued the CPD after harassment from his fellow officers and being denied job assignments due to his race. The same year, 16-year-old Julius Tate was killed in a SWAT sting under poorly documented circumstances.

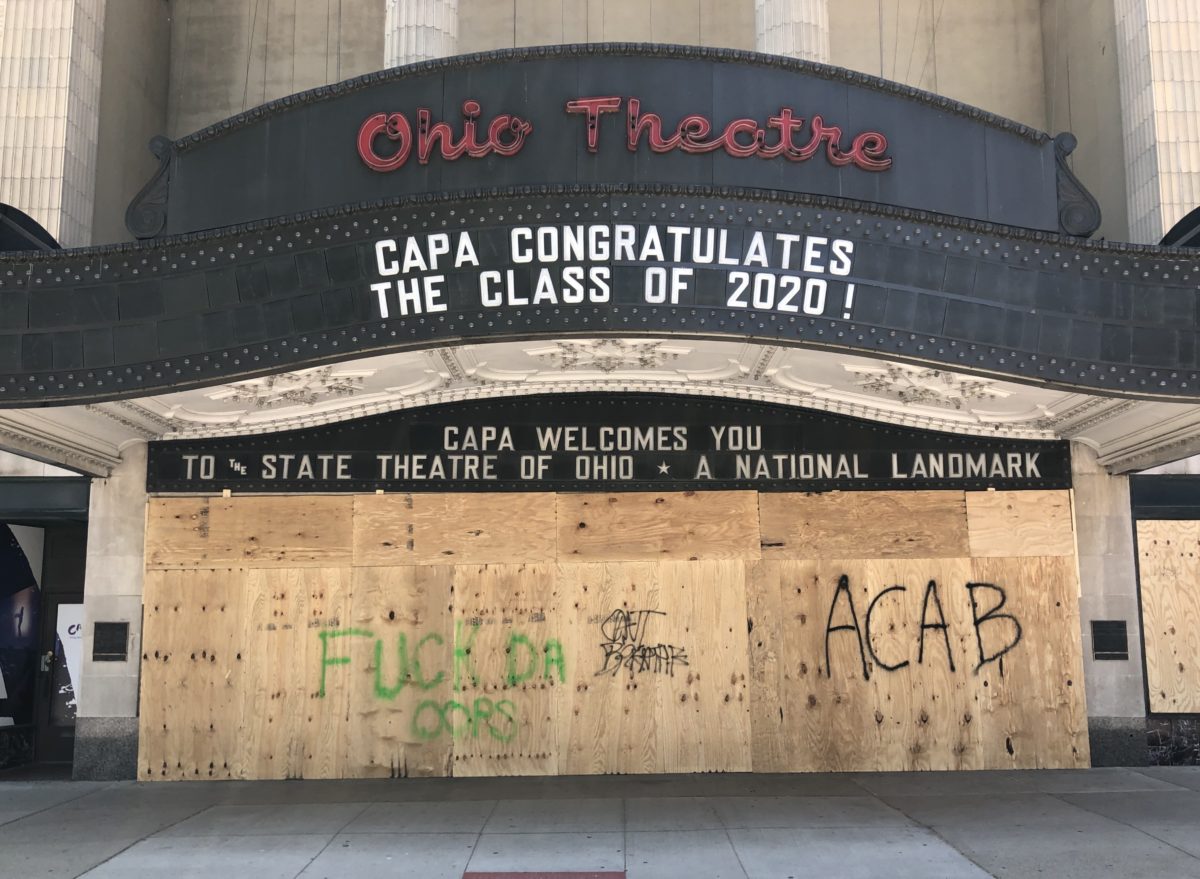

Since Thursday, protesters have held demonstrations in downtown Columbus. By Friday night, several businesses downtown, the Ohio Statehouse and the Ohio Theater had all sustained damage, five people were arrested and two police officers were injured. In response to the protests, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine requested aid from the National Guard, bringing the total number of states to do so to 8, in addition to the District of Columbia. Saturday afternoon, the CPD declared a state of emergency and instated a curfew, announcing that anyone outside without cause between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. may be arrested. An end date has not yet been announced.

DeWine’s call to the National Guard may remind Ohioans of another protest-turned-tragedy: the Kent State massacre. Four students were shot and killed and nine injured by the National Guard in a non-violent rally against the Vietnam War in 1970. The causes and victims of these two movements are obviously different. But they share the common thread of violence marring the peaceful demands of the people.

Saturday afternoon I spoke with someone who had participated in the protest that morning. Olivia Everett, 16, went with some friends to join what was listed in a Facebook event as a non-violent protest. She stood at the corner of High and Broad, alongside hundreds of other protesters, holding signs and chanting phrases led by a community organizer at the front of the crowd. Police had a row of bikes set up in a makeshift barrier, preventing protesters from entering the lot of the Statehouse.

According to Everett, “no violence had been going on at all” when police began pepper-spraying the crowd without warning. Apparently a young woman had tripped and fallen in the street that was being guarded by police when it began.

“I did not hear anything: They just started spraying,” Everett said.

She and her friends, all between the ages of 15 and 17, were hit by the pepper spray and ran away. But since the organizers were prepared with “stations for water and first aid” and had “medics going around,” they received aid quickly.

“Everyone was helping each other,” Everett said. “It was like a big family.”

That same day, the CPD was caught on video pepper-spraying Congresswoman Joyce Beatty, City Council President Shannon Hardin and Franklin County Commissioner Kevin Boyce without any violence from the protesters. Other methods of crowd control included firing wooden bullets and releasing tear gas.

“We turned around, and there was a SWAT van,” Everett said. “There was a giant cloud of tear gas coming towards us. So we were running away … and he [the van driver] swerves and almost hits me and my friend. And then he rolls down his window and starts cussing at us.”

My parent’s house, where I’ve returned for quarantine, lies two miles north of the state capitol building, the center of the protests, two blocks from a police precinct, and a hundred feet from a fire department. I’ve grown so used to silent nights as of late. But 10 minutes after curfew, sirens came from every direction. Helicopters hung overhead. For the first time in years, I found myself wondering if the distant pops I was hearing were from fireworks or gunfire. I hoped the former. Five minutes later I watched three young Black men walk in the direction of downtown. Just by being outside, they risked arrest.

We began on Sunday at a grocery store near my house around 10 a.m., joining a group that planned to march the two miles south to the statehouse. I briefly spoke with the organizer of the march, Kim Martinez, who used Facebook to get the word out. It was just one of many planned for the morning.

“We all saw, as a nation, that livestream of George Floyd. It was awful, it was heartbreaking,” Martinez said. “I think it’s something that finally has hit a head. And it’s something that we have to push forward if we want change.”

Martinez offered to the group of about 40 people water, snacks and masks for anyone who didn’t have one. (The entire day, I saw only a handful of people not wearing masks.) On a graver note, swim goggles were also distributed to protect against any spray irritants, such as tear gas and pepper spray, that the police may deploy as they had the last three days.

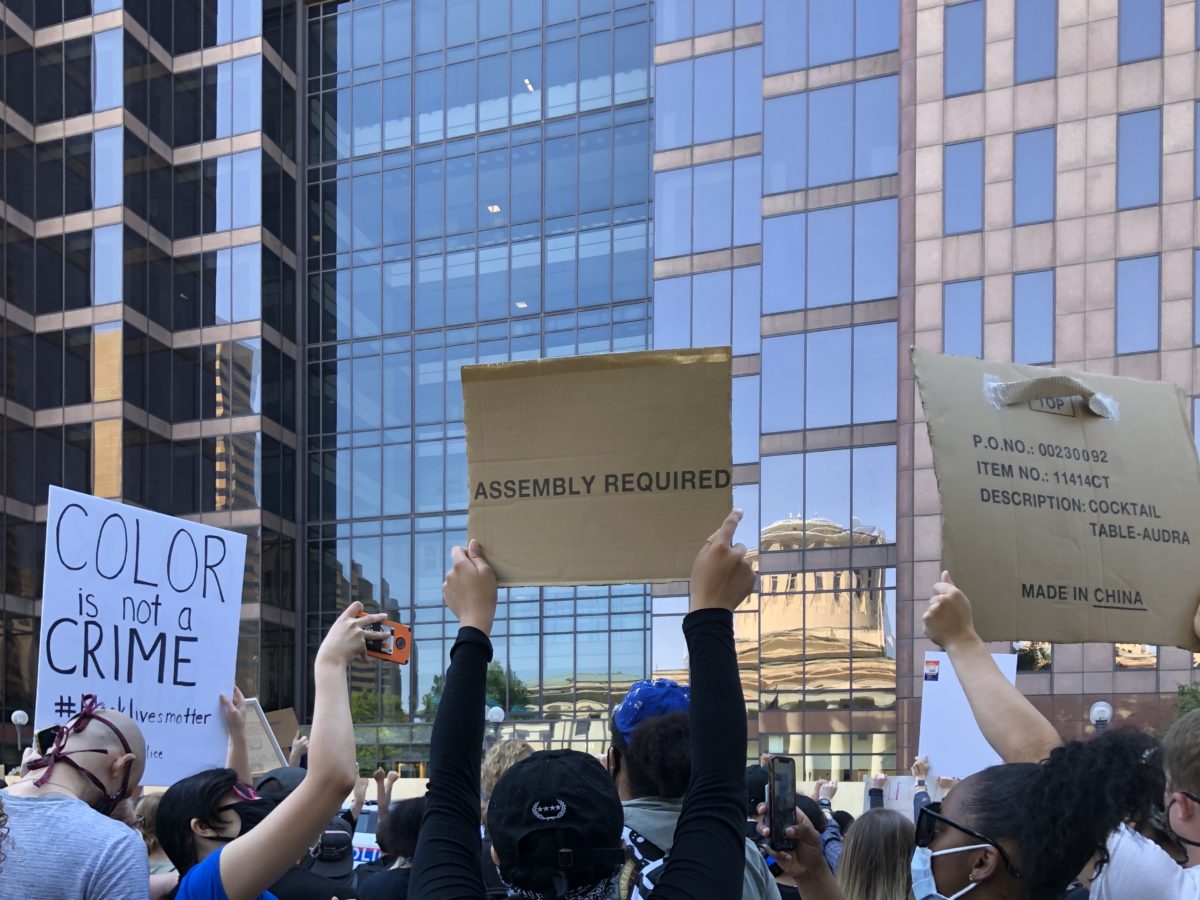

The march started in the Short North Arts District, which has arguably contributed to the recent gentrification of the neighborhood in which I spent most of my life. Artists of color turned the Short North into the cultural capital it is today, only for its residents to be priced out in place of wealthier, whiter people that wanted to live surrounded by the culture they were actively displacing. To see boards painted with messages of the movement such as “Black Lives Matter” and “no justice no peace” over the windows of all the upscale dining and retail establishments and fine arts galleries that didn’t exist 10 years ago was bittersweet, to say the least.

Nonetheless, the support coming from every direction invigorated demonstrators. The group I was following grew rapidly every minute. Passing cars honked their horns as people raised fists out their windows in solidarity. The crowd became a rolling boil of hope and indignation, in contrast to the sobering sights of boards on windows and cardboard signs begging for justice and peace.

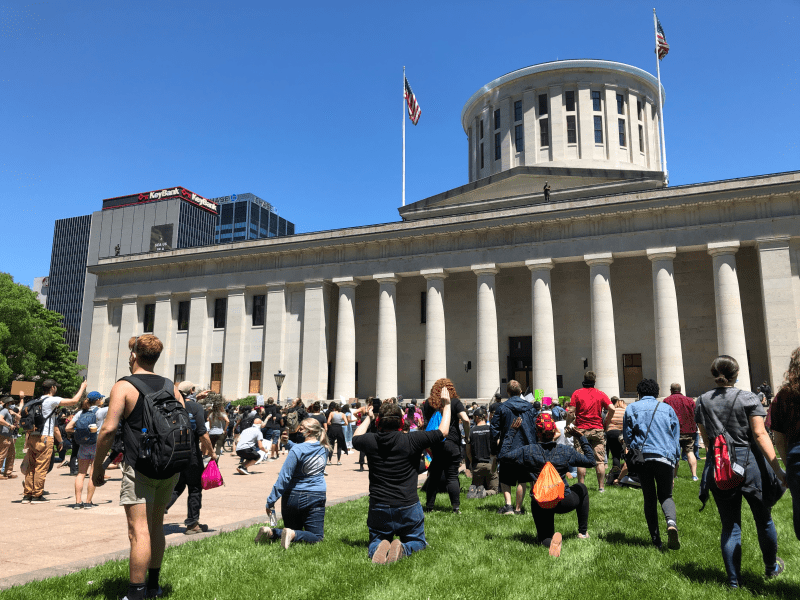

That Sunday, unlike the previous day’s demonstrations that Everett described, protesters were allowed to gather freely on the statehouse’s plaza. At least a hundred demonstrators were already there when we arrived. I immediately noticed the peacefulness of both the demonstrators and the law enforcement. The statehouse was guarded by Ohio State Highway Patrol officers instead of Columbus police. When I approached the barrier at the front, I heard not provocation but discussion. Nobody wanted conflict. Many highway patrol officers, some but not all of whom wore body cameras, spoke with demonstrators about the protests; from what little I could hear, (nobody was shouting at each other) the officers supported the protest.

I watched the crowd grow and grow to hundreds of people, chanting phrases such as “No justice, no peace, no racist police” and “Say his name, George Floyd, say his name.” Occasionally protesters would kneel or lie on the ground, imitating victims of police violence and chanting, “Hands up, don’t shoot.” In the crowd were people of all ages, even children. By noon on Saturday, police had deployed tear gas and pepper-sprayed protesters, so the presence of people under the age of 12 worried me.

Around 1 p.m., later than the time by which police had instigated crowd-control measures on Saturday, the protest remained peaceful as demonstrators began to march toward the police headquarters. At the police headquarters, no law enforcement officers were present, and leaders of the protest spoke.

“Look around you right now. Black people, white people, yellow people, brown people, men, women, we all different ages. They cannot stop us if we stick together,” said one speaker. Another speaker quoted Martin Luther King Jr., saying, “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

Afterward, the mass of demonstrators began a circuitous march around downtown Columbus. Cars were trapped in the street by the marchers, but many drivers weren’t upset by the inconvenience so much as supportive of the cause, perhaps even driving downtown knowing they’d be stopped. People walked in the middle of six-lane streets, between cars, under stoplights lit green and walk signs with blinking red hands. The usual rules of the road no longer seemed to apply. This is when I first really started to see Columbus police officers, but they weren’t wearing riot gear or gas masks. For the most part, they were just trying to empty the streets for protesters to walk through them.

The hands-off approach of law enforcement gave me a trickle of hope until I began to see the reminders of the previous day’s retaliation all around me: wooden bullets called “knee-knockers” shot into the crowd and never cleaned up, empty milk jugs and patches of baking soda solution dried on asphalt (both of which are often used to soothe victims of tear gas and pepper spray) left on the ground from Friday night, the heavy-duty gas masks and goggles worn by some protesters in preparation. How could the supportive atmosphere I saw then become one of fear, of people running and screaming under a cloud of tear gas lit orange by street lights?

Then we passed members of the National Guard stationed by the road. Nobody approached them. They held assault weapons and stood in front of tanks in military fatigues. These are the same streets I walked down to picnic by the Scioto River or see the July 4 Red White and Boom fireworks. The military equipment was superimposed onto the cheerful images of mine and millions of others’ childhoods.

Downtown Columbus is made of towering edifices of glass and marble, of steel walkways and bus stops and ample greenspace. Most of the time it looks unbelievably clean as if somehow it’s brand new every day. Now, graffiti and damage surround us. The graffiti embodies slogans of the Black Lives Matter movement, including those about George Floyd and his death, such as “BLM” and “I can’t breathe;” and of anti-police sentiment, like “Fuck 12” and “ACAB” (all cops are bastards).

The graffiti gives me this weird mix of pride and uneasiness. While, more than anything, I’m glad that these messages have found a platform here, I can’t help but feel unsettled by how not-normal it is. I’ve seen pictures of this happening in other cities, but the reality of the situation doesn’t set it until it’s in front of you in your own hometown. Like the National Guard, the sight of it is so surreal. Except in the case of the graffiti, the uneasiness comes not from a fear of violence, but rather this profound disbelief that everything could change so quickly. The energy of the march was here all along, lying dormant beneath the surface. And we are witnessing the inevitable eruption.

Around 2 p.m., the march returns to a protest in front of the statehouse. The crowd has at least doubled in size. A number of events that could have become an inciting incident were mitigated by demonstration leaders. Firecrackers were let off in the street exactly once. When an argument broke out between two protesters, the leaders led the crowd away before the situation escalated. They advised the crowd to stay on the sidewalks while five police cars gathered in the street and called out anyone who disobeyed.

Many people shared stories and sentiments with the crowd through a megaphone. A Black man wearing a bicycle helmet, who asked to be identified only as a government employee, led chants with such fervor his voice cracked and became raw. I asked him why he chose to demonstrate.

“I want a world that’s easier to love for people of color. And white people need to risk an act of love so people of color can live,” he explained.

One speaker then led the crowd in the Lord’s Prayer, before taking to the streets again. Demonstrators filled High Street in a mass longer than a city block. Cars joined the march with their horns in a short-short-long honking pattern to mimic the “Black Lives Matter” chant. People stood at the side of the road offering bottles of water and granola bars to those passing. Here again, I was overcome by the power of the moment, of the hope of hundreds marching and shouting and honking for a shared desire to end the widespread racial violence in our country. This was exactly the kind of peaceful protest that the Columbus police insisted wasn’t happening. By the time the group turned around, we were practically back to my house, so I returned home around 4:30 p.m., feeling as though the day’s march had been a success. No one had gotten hurt or escalated the situation, and everything I saw was a stark contrast to the chaos that Everett described as defining Saturday afternoon’s demonstration.

However, around 8 p.m., I heard from that friend that they had begun tear-gassing demonstrators. 10TV Facebook Live footage showed that large numbers of CPD officers were closing down parts of the street and forcing demonstrators to disperse around 7:30 p.m., a full 2 1/2 hours before the announced curfew. By 7:45 they had tear gassed demonstrators. According to a 10TV reporter in the livestream, the gassing began after protesters threw water bottles at police.

So the question remains: Why were police forcing them to disperse in the first place? No one was violating curfew. And from what I saw earlier, organizers of the protest were actively trying to create a peaceful environment. And before CPD officers arrived en masse, that was the case.

I decided to bike downtown an hour before curfew to take some pictures and see what was going on. The more people I spoke to, however, the less information I had. Nobody seemed to know why the tear gas had been deployed a few hours prior, what the police were planning or how many there were. I stopped at the corner of High and Broad, the same place that Olivia Everett described being pepper sprayed on Friday.

The atmosphere was completely different, the polar opposite of that morning. I saw over a hundred CPD officers in riot gear. SWAT vans raced down side streets. Some protesters remained, but much fewer. Many looked to me to be quite young, high school age. And they were jumpy. Every five or so minutes I’d hear screams and everyone would run, for no more than five seconds before they realized it had been a false alarm; no tear gas had been deployed.

“Do not run, we’re not going anywhere,” shouted one protester at those who fled, who mostly appeared younger. “Stop fucking running. Either y’all here with us, or you need to motherfucking go home.”

I now see videos of looting, images of smoke rising over buildings, hear about the protests destroying downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, and it’s so conflicting. I want these protests to be happening, even after seeing the damage done to my city. But that’s the hardest thing to square away, the damage and violence. I cannot say that every act of violence happening out there is performed by the police. But I don’t think I’ve ever experienced anything frightening in quite the same way as a crowd all running away from something at once. You see people run and before you know it, you’re running too. It’s a completely limbic response. You don’t think, you run. When there’s this much movement and apprehension, this much generational pain, is it really all that surprising when things turn violent?

I didn’t stay long; I wanted to be home before curfew. On my way back I watched more police officers than I had seen in my entire life block off a street that intersected High Street. It was unclear whether they were trying to keep people out of the action or keep them in.

After that chilling sight, I raced home, staying off High Street. I heard sirens the whole time and watched from alleyways as police vans sped downtown. At one point, I narrowly missed getting hit by a car racing down an alleyway. I made it home five minutes before curfew, shaken but unscathed.

I keep returning to this thought: If I, a white woman, feel so terrified right now, how do the hundreds of Black protesters feel? I imagine they feel more fear than I can possibly know. And it makes me think that that fear may be a part of the root of all of this: the day-to-day fear for one’s life that the American police system instills in Black Americans, and the bravery it takes to stand up to a system rigged against them. We are living at the culmination of hundreds of years of pain and injustice. And the only hope for changing the inequality so deeply ingrained in our society is exactly what we’re seeing today: a revolution.

The Columbus Freedom Fund is a community bail fund centered on Black liberation and freedom. It is currently accepting donations here.

Conatct Lana Tleimat at ltleimat ‘at’ stanford.edu.