A perennial problem faced by researchers in any field is making their work accessible and meaningful to non-experts. Art of Science 2020, organized by the Stanford Materials Research Society, creates a space for Stanford scientists from all disciplines to encounter their research creatively by translating their work into a piece of art. The virtual exhibition of these pieces gives the Stanford community the opportunity to engage with scientific research from a fresh perspective that imbues each project with a new significance and reveals unexpected insights.

The exhibition’s head organizer Dante Zakhidov, a Materials Science PhD candidate and a former President of Stanford Materials Research Society, who has poured many hours into planning this unique event each spring for five years now. “The purpose of Art of Science is to show that thinking creatively is something that pertains to all fields. There’s no reason why the creative thinking of each field can’t be recognized and celebrated by the others.”

Many of the pieces seen in the exhibition were not explicitly created for it—this kind of creative work is something many Stanford scientists and researchers already pursue. However, Zakhidov notes, “There’s currently no spaces on campus for people to do this kind of work. It’s hard to share it, because there’s not a time and place to do it within our departments. So that’s kind of my vision, to create the time and place that these people can share.”

For the first time in its nine year history, Art of Science 2020 is a virtual exhibition, running until June 19th. The judges received a record 132 submissions, representing work from 32 different departments and programs, from which they selected 35 finalists. These finalists include 28 works of visual art presented in a 3D VR gallery walkthrough as well as a traditional image gallery, six audiovisual entries and one planetary gallery. The great diversity of pieces demonstrates a fascinating range of interpretations of the meaning of “art of science.” As Zakhidov points out, “Every person that I’ve talked to has mentioned a different piece they’ve liked, and everyone is finding something unique that they like about these pieces, which I think is powerful.”

To interpret scientific research as it is presented in journals and conferences, you typically are expected to have a certain framework of knowledge about the field, which is necessary for appreciating the work’s scientific intrigue and implications. However, when it comes to artworks, people have intuitive and individualized ways of approaching them, of which there’s no one “right” way. By transforming scientific work into artistic work, Art of Science makes science more broadly accessible and intriguing.

We can appreciate a work of art at many different levels—for its aesthetic beauty, the story or message it imparts, the surprising connections it reveals, its situation within the broader context of art history and practice. Art of Science gives us further levels to connect with these particular artworks—the underlying data, theories and discoveries they represent, and the new perspectives on the world that they reveal for us. As a viewer, I was amazed at how the works we see in this year’s Art of Science exhibition worked at all of these levels.

The works in the gallery delight us aesthetically, showcasing symmetries and patterns that are particularly amazing because they come from the world around us, yet can only become visible to us through the guiding minds and sophisticated instruments of scientists. Savannah Cofer’s “Toobs for Noobs” shows an actual image of carbon nanotubes captured through electron microscopy. I’ve heard a lot about these tiny chemical structures but only ever seen theoretical models of them, never an actual image. The satisfying pattern and bold color scheme of Savannah’s photograph wouldn’t be out of place among the default backgrounds on the latest iPhone.

In fact, Many of the pieces would not at all be out of place in a modern gallery of abstract art, and yet upon reading their descriptions, we learn that they represent scientific data in innovative ways. Wiley Jennings of Environmental Engineering created a grid of overlapping dots of different shades of yellow and green, hilariously titled “Poop at the Beach.” Its simple aesthetic was inspired by the works of Mark Rothko, but its dots actually represent half a million measurements of fecal bacteria made at California beaches between 1995 and 2018, darker green representing higher levels of fecal matter, and yellower green indicating lower levels.

For people who may not ordinarily be interested in abstract art, the underlying data visualizations create another layer of meaning to connect with in these pieces. Ethan Nadler, Mark Chu, Tasker Hull and Douglas Guilbeault created a grid of 30 squares of varying shades between grey and blue, reminiscent of the works of German abstract artists Josef Albers who painted monochrome squares. Yet these particular squares represent a computational investigation of synesthesia, each of them demonstrating how Google searches for abstract terms result in sets of images with surprisingly coherent color schemes.

Many of the video entries, by adding music and motion to beautiful visuals, made for sublime, mesmerizing viewing experiences. If you only check out one piece of this exhibition, I recommend a video created by Miriam Haart titled AI Generated Landscapes using GAN Networks. The fact that AI can generate never-before seen landscapes that look like real places is mind-bending enough; then, by presenting the images based on their vector compositions, Miriam created a video where the landscapes smoothly bleed into one another in a continuously morphing journey through many vivid terrains, all set to calming piano music and sounds of nature.

Beyond the aesthetic level, many pieces in the Art of Science worked at the symbolic level to convey a message to viewers. Majo Lozano (Physics) painted diagrams showing the release of radiation in the form of electromagnetic waves and X-rays, in a piece that is both visually interesting and pedagogically instructive. Vince Pane (Chemistry) and Bruce Fowler created “Not Far Out!”, a sculpture constructed from plastic collected on the California Coast, depicting a man in a Hazmat suit surfing on a wave of trash—a work of art, a scientific demonstration and call to social and political action all in one piece.

I was struck by an amazing cluster of narrative and symbolic works around medicine and illness, which all took very personalized approaches that emphasized the subjectivity of the patient. In one such piece, Savannah Mohacsi’s (Human Biology) “The Body as Canvas” explores the practice of body painting as it relates to the doctor-patient relationship. Savannah describes the methods of her project: “I interview people about their lived experiences, and together we choose a site on their body, transforming it into a temporary canvas. This site maps their physiology and reveals symbolic imagery related to their visible and/or invisible identity that is linked to health, illness or injury.” In another, Maia Mossé’s (Medicine) poignant photograph “Their Hands” captures a cadaver’s hands in a folded posture evoking the human life they once led. These pieces suggest that medicine is a particularly critical place for art and science to collaborate, for science gives us the objective tools we need to understand the human body, while art allows us to express the subjective nature of any work dealing with human embodiment and experience.

Several pieces even succeeded in using artistic means to make philosophical statements about science and the role of the scientist in the modern world. “Feynman’s Disciple,” a mixed media piece by Vladimir Bacvanski (Stanford Continuing Studies), uses symbols to evoke the lineage of scientists guided by and building upon the work of countless others who came before them, as well as the window that science gives us into parts of the world we could not otherwise know. In one of my personal favorite pieces, Daniil Lukin’s “Scanning Electron Microscope: An Introspective Study,” a remarkable unedited photograph shows the inner parts of an electron microscope, captured by the microscope itself using an “electron mirror.” I loved this image of science literally self-reflecting, freeze-framing its tireless, fast-paced work in order to reflect on the composition of its own instruments and methods, and the biases perhaps inherent in them.

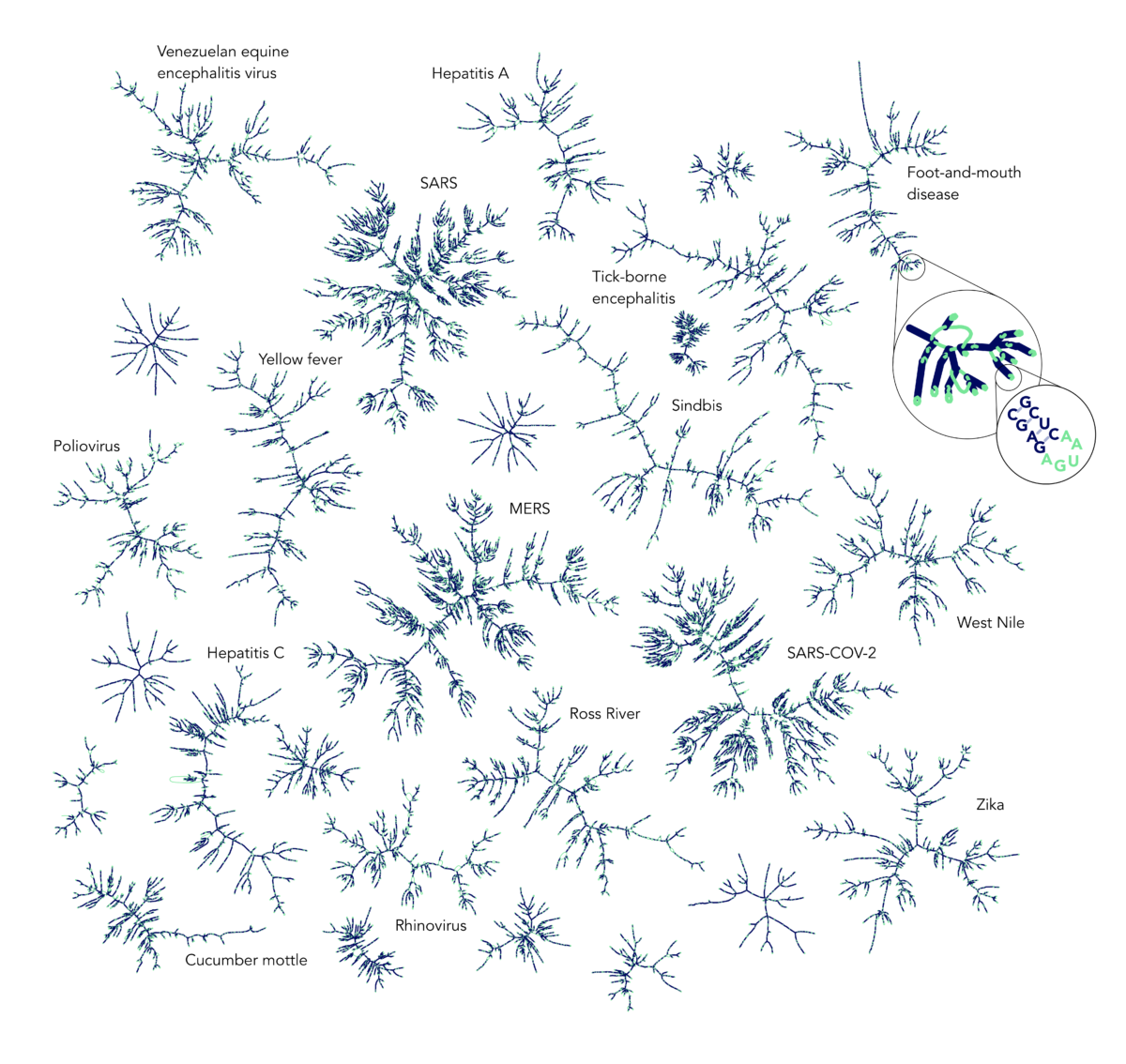

The creative visualizations developed by Art of Science contestants can actually provide new insights and intuitions for scientific researchers to further investigate. For example, Hannah Wayment-Steele’s (Chemistry) piece “When Art Goes Viral” uses an original visualization technique to give a better global view of the size and structure of viruses. As Zakhidov indicated, “This is not how genetic data is usually visualized, but Hannah thought that it was important to visualize it in this way, and the second she does, all of a sudden you see that SARS and SARS-CoV-2 are the same, in that they’re larger and more sophisticated than these smaller structures…These little structures don’t have names yet because they’re unidentified; in other words, they haven’t started wreaking havoc on the human population…This can start giving intuition to researchers that they might not have had before.”

By bringing science and art together, this exhibition suggests new ways of practicing both. Zakhidov hopes that scientists who view the exhibition will get inspired to look upon their work with fresh eyes. “I think this is the take-away for scientists—hey, my peers are using their creativity in this way, let me try that too.” For artists, the innovative approaches to art-making these scientists are taking can equally be a source of inspiration. “I hope artists realize that the art these people are making is something they may never really have thought about, and it’s cool and special in its own way…I hope it opens up ideas for collaboration, or ideas for how they can maybe reduce their own biases.”

In a student body that loves to pit “techies” against “fuzzies” and place people squarely in one group or another, this exhibition helps show us that the walls separating these domains are really artificial—creativity is at the heart of innovation and discovery in all fields. “I think that the fact these boundaries exist are due to the ways that pedagogically we’ve been instructed from a young age. Because society has had to institutionalize these forms of education, it’s created these departments and ways to provide instruction, which I think is beneficial. But in doing so, the downside is that these walls that were built to help define these spaces, now also serve as walls that make things inaccessible…This event is one that allows us to cross these boundaries, because it promotes these underlying ideas of creativity, versus school of thought.”

Because Art of Science is organized by Materials Science students, their submissions tend to be biased towards the physical and biological sciences, but Zakhidov says he would love to see more submissions from humanities and social science researchers, who are collecting data, constructing arguments and drawing conclusions in equally rigorous ways. For Zakhidov, “science” is about certain modes of thinking, not a particular subset of academic disciplines.

Viewing this exhibition reminds us that no matter what subject you study and no matter what means you use to express yourself, we are all trying to find meaning in this complex world and hopefully make it a better place for those who will come after us. We have a whole host of methods available to us for learning things about the world and about ourselves, and there is no reason why we shouldn’t make use of all these diverse approaches to seeking truth. Despite Stanford’s efforts to encourage interdisciplinary study, too many of us consider the world with only one set of tools. Rather than walling ourselves off into hyper-specializations and seeing the world through one lens, let’s challenge ourselves to think creatively and see differently, for beauty can strike us in the most unexpected places.

Acknowledgements: Art of Science is sponsored by the Materials Science and Engineering Department, the School of Engineering, the Graduate Student Council, the Graduate Students in Electrical Engineering, and the Stanford Energy Club. Art of Science is organized by the Stanford Materials Research Society. Organizing Committee: Michael Braun, Christina Cheng, Risa Hocking, Elissa Klopfer, Andrew Lee, Olivia Saouaf, Dante Zakhidov.

Contact Carly Taylor at carly505 ‘at’ stanford.edu.