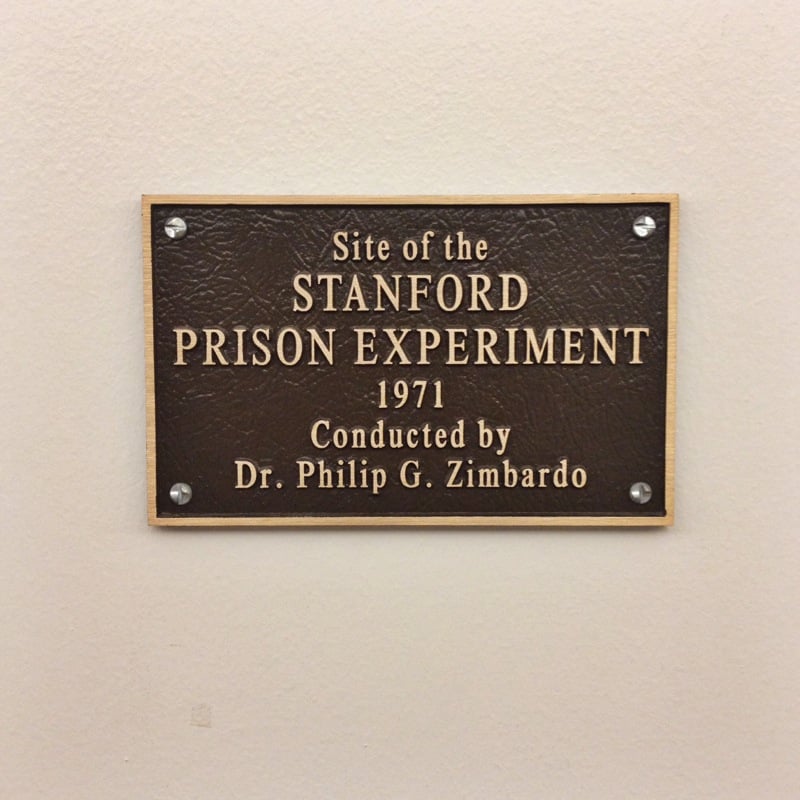

On an August morning in 1971, police officers drove around Palo Alto to arrest nine college boys for violations of Penal Codes 211, Armed Robbery, and Burglary, a 459 PC violation. The officers read them their Miranda rights and conducted a search, having the suspects spread-eagled against the police car. They were handcuffed and driven to the station. This marked the beginning of the famed Stanford Prison Experiment conducted by Professor Zimbardo, attempting to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power.

Recently I’ve been thinking about how we have gotten to a state in which our cops comfortably kill Black people, and I suspect the answer in part relates to the power of institutions to influence individual behavior—the very question Zimbardo posed fifty years ago. Here I am likening the student prison guards to real police officers, and the student prisoners to real Black people. While the comparison may seem drastic, so do the statistics of police brutality, such that it is a leading cause of death for young men in the United States. Over one’s life course, about one in every 1,000 Black men can expect to be killed by police. These statistics are uniquely American, separating our police force’s use of violence and racial profiling from that of any other nation. The demand to defund the police may seem radical given their international ubiquity, appearing to be a necessary part of any lawful society. Yet it is the positioning of this organization in America that makes our police uniquely vicious, which is why activists across America are calling for its defunding.

In the Stanford Prison Experiment, 18 participants were randomly split into nine prison guards and nine prisoners. Despite the elaborate set-up including a real arrest, steel bars, cell numbers and costumes, within the experiment the only thing that differentiated the prisoners from the guards was the perception of power. Taking place over a week, theoretically the participants could have existed amicably: prisoners socializing within their office-turned-cells, and guards within the corridor. Yet to the shock of Zimbardo and his team, the guards rapidly abused their power, using a fire extinguisher to shoot a stream of “skin-chilling carbon dioxide,” forcing prisoners to defecate in a bucket which caused the prison to smell of urine and feces, and utilizing various modes of psychological abuse. In a sense, the experiment was about the extraordinary evil that results from the magnification of power imbalance.

While this imbalance inherently exists between any nation’s police and citizens, it is especially trenchant in America due to its history of Black derogation. While the founding of our nation can be told through the narrative of freedom and democracy, it was built on the vigorous exploitation of Black people beginning from chattel slavery to lynchings and Jim Crow, all the way to our current systems of mass incarceration, private prisons, and racist, unaccountable policing practices. A history of racial genocide is not unique to America—what is unique is how the history is undealt with.

In Germany, it is impossible to walk two-hundred feet without seeing a reminder of the Holocaust; swastikas have been banned; the country has and continues to pay reparations. While the conversation about slavery reparations has been broached time and again, most elected American officials have never seriously considered it. Instead, Black Americans get thrown phrases such as “reverse racism” and “all lives matter,” in a culture that extols celebrities stealing from and profiting off Black culture. As long as our country refuses to face and address its history of racial trauma, there will always be a disproportionate power imbalance between police officers and Black people, which is among the many reasons it has become necessary to defund the police.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been partially invalidated, most prominently on the grounds that the guards were instructed to be cruel. Yet their decision to actually carry out the violence may even more accurately reflect the realities of police brutality. A large reason why George Floyd’s murder has caused such an uproar is because it was not an isolated incident, but part of a pattern. In observing prior police murders of black men, Floyd’s officers were being primed—yet it was still their decision to not only accept, but to execute that same behavior. As such, the experiment’s findings may more accurately be that, once permitted, authority figures are willing to carry out violence, which can still be used to cite many of the inherent problems with the police force.

The guards’ attire included mirror sunglasses which, by hiding their eyes, personified anonymity, allowing them to conflate themselves with capital Authority, thus deindividuating their personal crimes by sourcing it back to their larger team. In our real police force, this herd immunity is pillared by for-profit policy-making companies such as Lexipol, which is designed to help police officers navigate laws in ways that will make them less liable to be charged of any crime.

Another telling aspect of the experiment is the specific punishments the guards decided to use on the prisoners. In addition to the examples already listed, the guards imposed solitary confinement, forced menial work such as cleaning toilet bowls with their bare hands, and physical work such as sustaining push-ups or jumping jacks for hours. The participants were college boys, and those arbitrarily chosen to be guards were given no specific training. Naturally, the punishments they enacted could have only been extracted from what they had consumed in the media throughout their lives, whether that be from television, news reports, etc, punishments that they were raised to believe were justified. Humane treatment of prisoners is a subjective matter, and the fact that these boys believed these actions to be humane speaks to the values of the culture they were raised in, which is the same culture that cultivates our police officers. The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade and countless others could have only been committed if the police officers believed their actions to be socially acceptable. These officers believed their racist and violent acts to be acceptable within our current policing system.

When society moves forward, we instinctively look outward to the world we don’t know in order to inform ourselves. Yet it is often true that we do so without even sufficiently examining parts of ourselves, of our institutions, that already contain the knowledge we need. Much of the inherent faults of the police and criminal justice system were evidenced fifty years ago on our very campus, thus demonstrating yet another reason why history cannot be relegated to relics, but rather that it must stay afloat in our psyches.

Stanford is a historically practical institution, prioritizing technology and innovation, demonstrated today by the near half of students receiving degrees from the School of Engineering. While these studies are important, it is times like these in America, when we are confronted with the genocide of Black people by our own “peacekeepers,” that we must consider if innovation is the thing our nation currently requires. It is in asking the right questions and insisting on being thoughtful about our education that we keep Stanford close, even from afar.

— Chloe Cay Kim ’21

Contact Chloe Cay Kim at cay ‘at’ stanford.edu

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to eic ‘at’ stanforddaily.com and op-ed submissions to opinions ‘at’ stanforddaily.com.

Follow The Daily on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.