With the recent evidence of America’s flattening COVID curve, the prospect of reopening the economy is suddenly in reach. We now face a critical decision between easing shelter-in-place directives and extending them into the summer. In New Jersey, indoor dining remains prohibited. In Florida — which set a record high in daily reported cases for three days in a row this weekend — restaurants can now operate at 50% capacity and most beaches and theme parks are open. Inconsistencies in official guidance for the pandemic have left our nation unsure how to proceed. But by underestimating the need for cooperation in our response to COVID-19, we are trapped in a real-life prisoner’s dilemma. What the prisoner’s dilemma can teach us about coronavirus is the importance of genuine cooperation during this time, both in the issuing of guidelines across state and national borders and in our own personal actions.

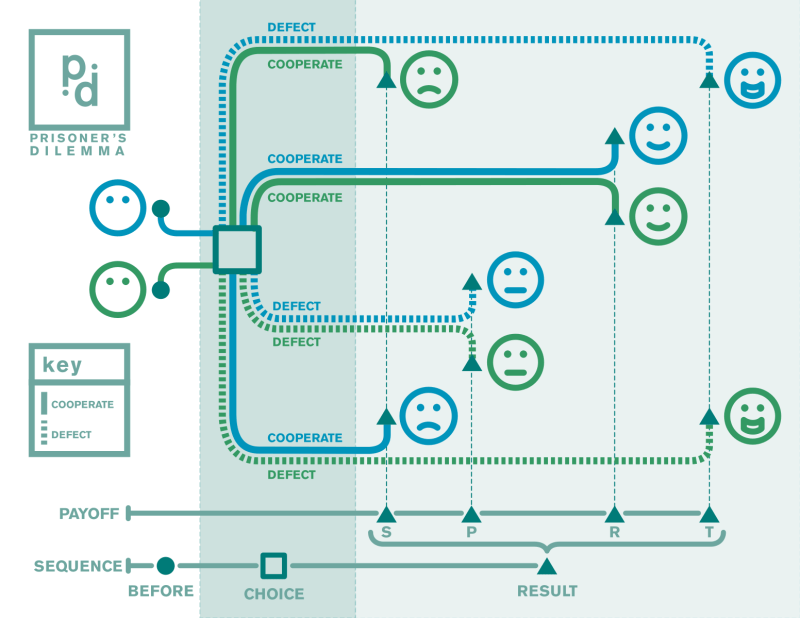

The prisoner’s dilemma is a concept in game theory that demonstrates how two agents acting in their own self interest both end up with a worse outcome than if they had coordinated their behavior.

Suppose we simplify the situation to a two-player game between governors who, due to a lack of federal direction, are the primary decision makers. The states of California and Arizona incur immense business losses if both continue social distancing and shelter-in-place directives. If both governors Gavin Newsom (California) and Doug Ducey (Arizona) decide to reopen their economies, the states incur an even greater loss as the disease spreads exponentially and deaths increase.

The penalty is different, however, if only California continues a shelter-in-place order. The effects of one state’s policy will never be confined to just that state because movement is fluid across borders. The penalty for California is now higher than the previous two scenarios, because not only does California under lockdown lose business, but it also loses an additional amount in increased disease transmission due to Arizona’s deviation. Arizona, on the other hand, has a small loss because it benefits from both an open economy and reduced transmission from California.

Given these penalties, neither governor has an incentive to continue the lockdown. Each should choose not to extend the shelter-in-place because neither has anything to gain by changing their strategy in response to the other player’s strategy. This is called the Nash equilibrium outcome of the prisoner’s dilemma. Had the governors communicated their strategy, they could have coordinated a response of moderate reopening with an aim to minimize COVID cases and maximize business survival.

The prisoner’s dilemma model extends to local government responses and even individual responses. If a small business owner stays closed, they lose money and face the risk of going out of business. If the owner reopens, not only will they make money but could permanently take market share from competitors who are closed. But if everyone reopens, there is a disadvantage of both disease transmission and a competitive market.

Similarly, given our freedom of choice on whether to wear a mask, each time we step outside we are decision makers in the game. Wearing a mask protects others from our own spread more than it protects us from others. A mask reduces the amount of aerosols and droplets in the air that spread directly to a person or contaminate surfaces. Thus, if we do not wear a mask while others take the precaution, we negatively impact their outcome.

We cannot know the exact value of the penalties from these decisions, because quantification relies on several unknown variables: the value we place on human lives, the downstream effects of today’s job losses several years from now and the expected time to a vaccine or treatment, to name a few. But no matter what penalty is higher, if we at least cooperate with each other in our response, we can minimize the massive losses that arise simply due to a lack of coordination. As Stanford professor Matthew Jackson describes it, “Just like you can’t treat a termite infestation by fumigating only one room in a house, you can’t control the coronavirus pandemic by targeting interventions to a specific region or country.”

The prisoner’s dilemma demonstrates that when individuals pursue their own self-interest, the outcome is worse than if they had cooperated, regardless of what policy they collectively choose. In a time where lives are at stake and we interdependent on each other, game theory reminds us of the significance of cooperation and collaboration in the decisions we make — from the individual to the international scale.

Contact Annika Mulaney at annika.mulaney ‘at’ alumni.stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to eic ‘at’ stanforddaily.com and op-ed submissions to opinions ‘at’ stanforddaily.com.