This article is the second and final part of a series exploring the musical careers of student musicians during quarantine.

In the world of performing arts, the spotlight often — and rightfully so — shines on individual performers themselves and the talent that distinguishes musicians from each other. As such, it may seem feasible for artists and student musicians to continue their passion while in isolation, as COVID-19 would enforce.

Yet according to violinist Hannah Walton ’22, life as a musician under shelter-in-place restrictions presents a series of unprecedented challenges and obstacles. Principally, the lack of face-to-face interaction with peer creators and live audiences in digital music production complicates the situation at hand.

In an interview on transitioning to digital performances, Walton said having to change the way music is traditionally showcased reminded her of the “conversational aspect” that comes with playing music collaboratively. “It’s difficult to even talk to people online… it’s even harder to do music,” she said.

Despite the challenges introduced by adapting to pandemic life, some Stanford student musicians are using isolation as an opportunity to experimentally evolve performance methods and transition to digital showcases.

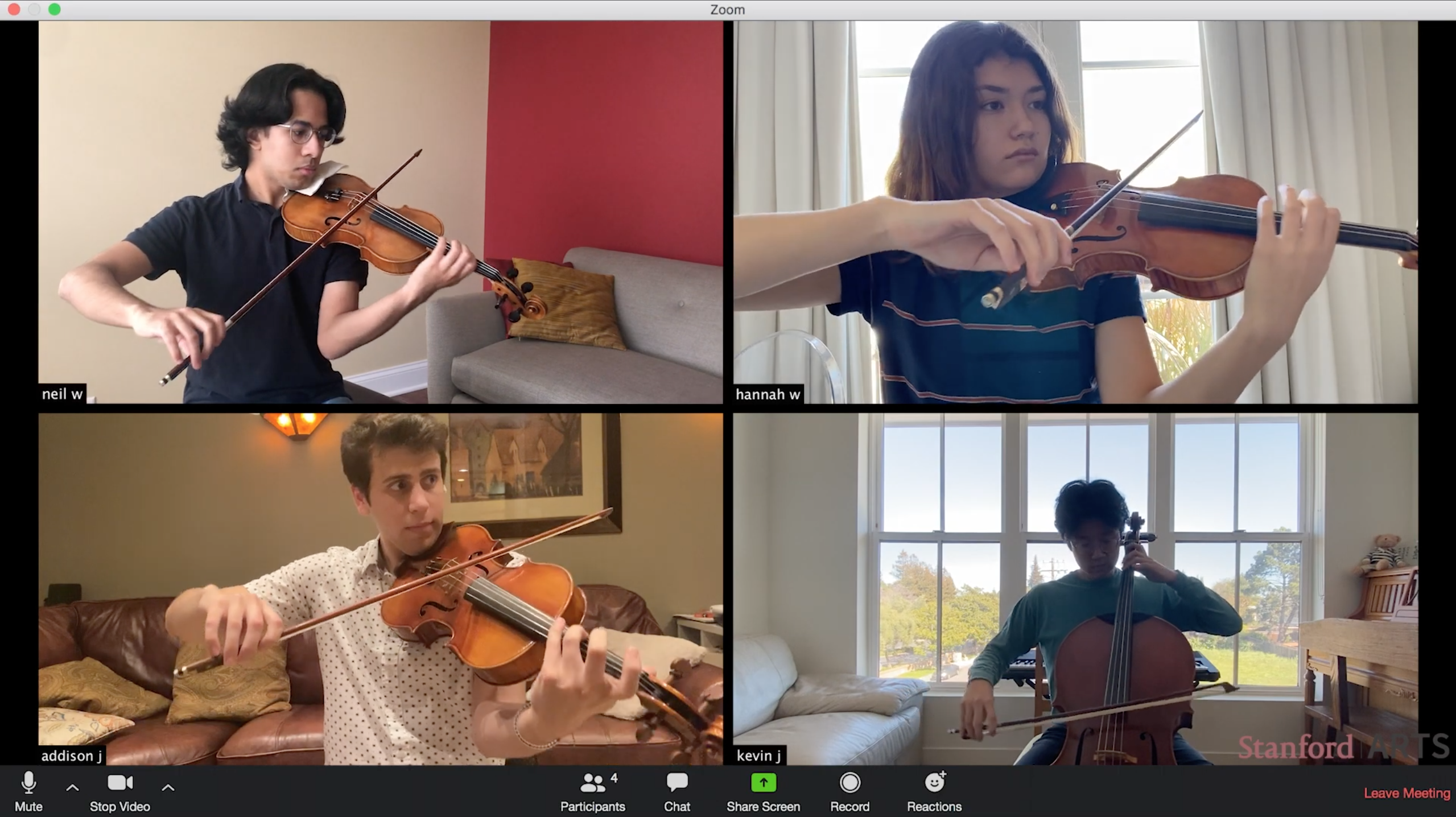

Walton is one-fourth of StringTime, a student quartet and recipient of Stanford Arts’ COVID-19 Creative Community Response Grant, who’s doing precisely that. The group’s members — violist Addison Jadwin ’22, cellist Kevin Jung ’22 and violinists Neil Wary ’22 and Walton — used the money they received in the grant to purchase recording equipment for themselves, which they each use to record their part of a song.

“We stated in our grant application, ‘We want this money so that we can each buy tripods and mics.’ So we each have our mic and tripod, and the mic starts recording once we start playing,” Wary said.

After selecting a piece, the group begins studying the score on a Zoom call together.

“I’ll share my screen, we listen to the piece together, and talk about how we want to interpret the piece — mood changes, tempo changes, et cetera — and then after that we individually record each piece,” Wary said.

Jung further clarified what the process of recording each part remotely without being with the full quartet is like, “We start with just the metronome. The first person records their part while listening to it in their ear, and they send all of us that track. And then the next person records over that track, and so on and so on until everyone has recorded it.”

After each part is recorded, Walton edits the sound to clean up the track and ensure the audio runs smoothly.

For the group’s first virtual performance, they performed the fifth movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 13 in B-flat major, “Cavatina.” In keeping with the theme of performing remotely, Wary edited the videos each quartet member took of themselves playing to make the performance look like a Zoom call, which they then published on the quartet’s YouTube.

The group agreed that they all missed the aspect of having real-time feedback and reception from an audience. “At least for me, I didn’t realize that half of the fun that I had in playing music was seeing other people listen to it and playing with other people,” Jung admitted.

To Walton, publishing performances online makes it easier to reach a broader community, especially those who are unable to visit Stanford campus to attend concerts, noting, “My family lives far away, so it’s nice to be able to send [performances] to them that they otherwise wouldn’t be able to make. I have something that I can share with them that they normally wouldn’t be able to view.”

StringTime isn’t the only group taking advantage of the extra time at home to perform digitally for their community. Student hip-hop artist and member of collective SupaStas Entertainment Seyi Olujide ’22, who performs as Lil Seyi, performed digitally for Off The Record, The Daily’s concert series, in early June from his home in Maryland.

Olujide describes his music as deeply personal and close to his heart. At the forefront of the hip-hop scene, his music paints bold strokes in listeners’ minds but stays grounded with soulful lyrics. Olujide’s single “Evergreen” is evidently a choice song — it reached over 36,000 listens on Spotify alone.

A significant aspect of his music, he says, is making sure each song is truly his own creation, untainted by others’ opinions.

“If I like it, if I would listen to it on my own, then I know it’s good enough to be put out,” Olujide said, recognizing that not everyone is going to like the same music.

Though Olujide is primarily a recording artist, he’s performed publicly a few times with an Afrobeats band called Remedy based out of his hometown. Despite his prior experience, Olujide’s performance with The Daily was one of his first experiences as an independent performing artist. He remembers the performance as a learning experience.

“That was one of the first times I’d ever performed completely solo,” he said. “And I was kind of freaking out, wondering, ‘How do I perform?’ Being a recording artist is a lot different from performing, and even more so… via Zoom.”

Though Olujide stated he doesn’t currently have any future plans to perform digitally, he noted that spending more time at home has given him the opportunity to release new songs independently.

“You do a lot of self-reflecting when you’re in isolation and when you’re not surrounded by other people. You learn how to prioritize what you value, what’s your self-worth, and things like that, and that gets spilled into the music,” Olujide said. He views making music collaboratively as more for enjoyment, whereas making music in isolation is a more “calculated” process.

“You think about what your impact is going to be,” he said. “You think about who in your audience is listening.”

Contact Sophie Sullivan at sophiemsullivan ‘at’ gmail.com.