The camera didn’t attract much attention.

It was perched in a corner of San Francisco’s BrainWash cafe and offered an unobstructed sweep of the room. That’s probably why the owners placed it there, and also likely what made it so appealing to the authors of a 2015 Stanford paper on using artificial intelligence (AI) to pick out people in crowded scenes.

The camera streamed its footage live on the internet, where it was collected by the Stanford researchers to train and validate their algorithm’s effectiveness. Clips from the database, preserved on YouTube, show BrainWash customers milling about, ordering coffee or muffins.

None of them look like they know they’re going to become the raw material for a computer vision dataset that will be downloaded dozens of times around the globe, appearing in Chinese research linked to human rights abuses and sparking national concern over the power and potential of computer vision and facial recognition software.

A month after it was mentioned in the Financial Times on privacy concerns over computer vision, Stanford removed the Brainwash dataset from its public online archives “at the request of the depositor.”

The Financial Times also referenced similar datasets created by Microsoft, Yahoo and others that compiled publicly available photos or videos for the purpose of training powerful facial recognition algorithms. The proliferation of these datasets is both a testament to and the cause of the rapidly improving accuracy of this technology. Driven by datasets like Brainwash, AI-powered computer vision algorithms have vaulted from an academic concern to the driving force behind street cameras, photo-sharing apps, police databases and beyond.

This proliferation raises important questions about not only computer vision, but also the methods used to create it. Many of the people who appear in these datasets never consented to their likeness being used to train or test the technology. This lack of disclosure has drawn widespread concern from lawmakers and activists.

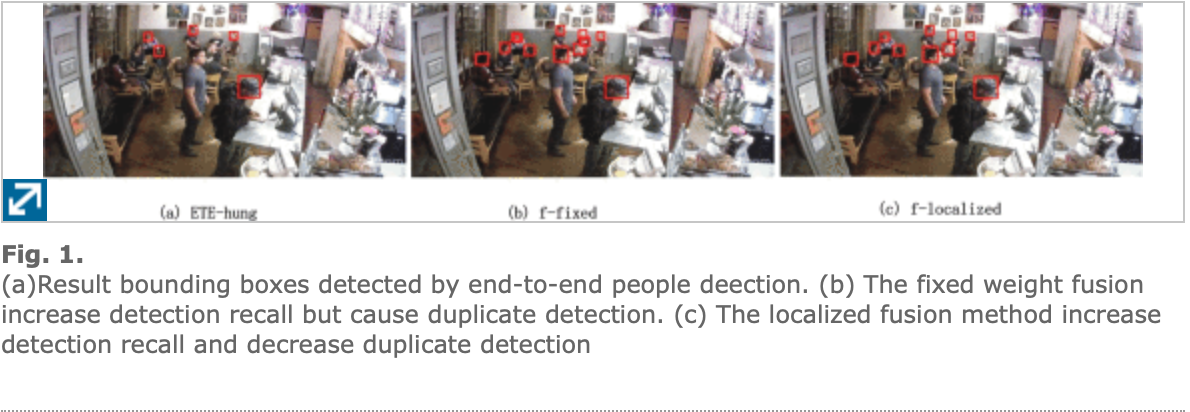

The people-detection algorithm developed by the Stanford paper can identify moving heads in a crowded video, but it isn’t facial recognition software that can identify a person from a headshot. Most faces in the brainwash dataset are blurry and difficult to distinguish. Nevertheless, both algorithms are built using similar AI techniques, require large datasets of pictures or videos of people and have drawn scrutiny from the press and privacy advocates.

There are few laws prohibiting the use or creation of facial recognition algorithms, though public debate surrounding the issue is increasing. Police use of facial recognition has drawn particular attention from lawmakers and activists. The issue has become increasingly poignant in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, tensions with law enforcement and the higher inaccuracies many facial recognition have with minorities.

“A person’s face is a unique identifier and one’s photo shouldn’t be used for these models unless there is express consent given to have your information used to build a database,” California State Assembly member Phil Ting wrote in an email to The Daily. Ting sponsored a 2019 California law that placed a three-year moratorium on police departments using facial recognition surveillance.

Despite Ting’s concern, there are few legal barriers to building datasets from photos or videos taken in public, as the Stanford team behind the Brainwash dataset did.

“I’m not aware of a law that would prohibit this from happening,” said Matt Cagle, a technology and privacy attorney for the ACLU, of the team’s data collection. “But that doesn’t mean that it’s ethically correct or should be permitted. This is a really important privacy issue and it raises serious privacy concerns.”

The 2015 Stanford paper was authored by three University affiliates: Russell Stewart, Mykhaylo Andriluka and Andrew Ng. Ng forwarded a request to comment to Stanford’s Media Relations department. Andriluka and Stewart declined to comment.

Computer vision and faces

Famed for the ability to learn and then find patterns, AI has delivered stunning advancements in computers’ ability to decipher hand-writing, understand speech, recognize faces and perform a multitude of other tasks once thought impossible to automate. The power behind its success lies in the large datasets the algorithms are trained on, from which they learn the patterns and idiosyncrasies necessary to demarcate something as variable as handwriting or facial geometry.

But to ensure high levels of accuracy, AI algorithms need a lot of training data. It’s not enough to just have a few pictures; researchers like Ng, Stewart and Andriluka often obtain their best results with millions of data points.

If there’s one event that shows the importance of large datasets for AI algorithms, it’s probably the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). The competition was first proposed by Fei-Fei Li, now a Stanford computer science professor and co-director of Stanford’s Human-Centered AI (HAI) Institute. When ILSVRC began in 2009, Li had just published the ImageNet database containing 3.2 million images organized into 5,247 categories.

Teams developed algorithms for the competition and were judged on their ability to identify objects in pictures taken from the ImageNet database. The competition was a convenient way to publicize the dataset as teams used its large collection of pictures to train their algorithms.

When the competition retired in 2017, the image recognition error rate for most teams had fallen from over 25% to 2%, firmly establishing the idea that more data could lead to better algorithms.

Large datasets of pictures started blossoming, published by private companies or academic researchers, that other developers could use to train and evaluate their own algorithms.

In 2016, Microsoft published the MS Celeb dataset, claiming it contained 10 million pictures of 100,000 celebrities or public figures. A closer look revealed it also included pictures of privacy researchers, journalists and political activists. None of the subjects had been informed of their inclusion in the dataset, and Microsoft deleted it after a Financial Times investigation in April 2019.

In a similar incident, Duke took down a dataset of students filmed walking across campus after an internal investigation determined the study violated the terms of its Institutional Review Board approval by making the data public.

Similarly, in 2014 Yahoo created its MegaFace dataset from pictures scraped off public Flickr accounts. The dataset includes pictures of children posted to the website by their parents, but Yahoo didn’t provide any notice that it was uploading the photos to a facial recognition dataset. Each photo in the Megaface dataset includes a link back to the original Flickr photo, allowing individual faces to be traced back to the account that posted them.

Ethics and privacy in the internet age

Even the smallest of these datasets contains hundreds of thousands of images. The sheer number of photos or videos needed to train facial recognition algorithms makes it impractical for researchers to collect the data by recruiting study participants one by one, so they often turn to scraping the internet. Stanford’s Brainwash dataset, for example, was pulled from Angelcam, a service that lets businesses broadcast live camera footage onto the internet.

Stanford declined to comment on whether patrons of the BrainWash cafe knew they were being filmed, or that the footage would be included in a dataset used to develop people detection algorithms. University spokesperson E.J. Miranda affirmed that “Stanford respects and is committed to protecting the privacy of individuals at Stanford and in the larger community.”

Research that might affect the privacy of individuals is subject to approval from a number of different University offices. According to Miranda, studies that involve datasets like Brainwash might require approval from the University Privacy Office, Research Compliance Office (which manages Stanford’s Institutional Review Board, or IRB), Information Security Office and Ethics and Compliance office. “Together,” he said, “they help ensure that Stanford carefully considers privacy and ethics in research, and complies with the numerous laws regulating our activities worldwide.”

University research is also governed by a set of privacy standards that seek to protect the safety and privacy of individuals involved in studies. The standards state that, at a minimum, experiments should only collect data “that is directly relevant and necessary” to the experiment. The privacy standards also require researchers “provide a notice that clearly and simply describes how Stanford plans to use the data, including the specific purposes for collection,” before the data is obtained.

The Brainwash paper doesn’t mention any notice given to the cafe patrons that their images were being collected for research, and Miranda offered no further clarifications. In an email to The Daily, Miranda noted that Stanford researchers didn’t explicitly collect the data; rather, the videos were taken from a “public webcam… placed in the café/laundromat by the owners of the business and the images were livestreamed on the internet.”

Stanford applies a lower degree of scrutiny over the privacy of individuals if the raw data is not created by the researchers, according to Miranda. Since none of the paper’s authors installed or operated the webcam, normal research rules governing privacy don’t apply.

“Informed consent is required by the IRB in many cases under federal research rules, but not where existing images are used from the public domain in this context,” Miranda wrote.

This raises questions about the ability of researchers to skirt IRB review of facial recognition data by working with, perhaps unwitting, private partners. If Stanford researchers obtain film or pictures from a business, what privacy safeguards can that business’ clients expect?

Stanford’s IRB declined to comment on the matter, and the Information Security Office and Privacy Office both redirected a request for comment back to Miranda.

Another of Stanford’s guidelines requires researchers, “to the extent practical, give individuals explicit choice and control as to how their personal data will be used and disclosed.” Miranda did not elaborate on whether this provision extends to privately-collected data used in Stanford research, nor do the Stanford privacy standards clarify the matter.

Another data privacy guideline requires that individuals be allowed to “review their collected personal data and … correct, supplement or delete it.” No mention in the Stanford paper is made of having allowed individuals in the Brainwash dataset to review or remove themselves from the dataset.

The control individuals have over the use of their likeness is also complicated by the openness of academic research. No data is kept on all the individuals who viewed or downloaded the dataset from its publically accessible Stanford SearchWorks page, but numerous citations appear in papers from other universities in the U.S., Switzerland, France, the Netherlands, India, Canada and China, according to internet privacy researcher Adam Harvey.

Some Chinese researchers who cited Brainwash had affiliations with the National University of Defense Technology, a military university controlled by China’s Central Military Commision, and with Megvii, a privately-owned Chinese company currently blacklisted by the U.S. for the role its facial recognition technology allegedly played in human rights abuses against China’s minority Uighur population.

Megvii has protested its blacklisting, claiming that they obey all applicable laws and “require [their] clients not to weaponize [their] technology or solutions or use them for illegal purposes.”

“People are not okay with the idea of having their faces collected and scanned and used to build a surveillance system that might get sold to an authoritarian regime for oppressive surveillance,” said Cagle. “This study really underscores why people should have a say in whether their faces and their biometric information is used as the raw materials for dangerous facial recognition systems.”

But according to Miranda, “Once research materials are made public, the University does not track their use.” Stanford’s guidelines on privacy clarify that its standards “reflect best practices” and “may not be followed by Stanford in all circumstances.”

Beyond Stanford’s guidelines, California residents have little protection from their image being used in facial recognition datasets without their knowledge.

“I think consumers come up short here when it comes to research uses and there is little to be done to their relief under current law,” wrote Albert Gidari — Consulting Director of Privacy for Stanford’s Center for Internet and Society — in an email to The Daily.

California took a step toward regulating the collection and use of personal information with the 2018 passage of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which went into effect Jan. 1, 2020. The law gives consumers the ability to delete some personal information collected by businesses, opt out of the sale of their personal information and be informed about what type of information is sold to third parties, among other rights.

However, the CCPA only applies to certain types of private businesses, and it wouldn’t have affected the creation of the Brainwash dataset by academic researchers, according to Gidari.

“Consumers captured in 2015 by video in a public place in [California] where the collection is not hidden or surreptitious have few remedies under [state] law to protect them,” Gidari wrote.

Gidari also noted that because the CCPA only applies to California residents and California companies in California, “those researchers could share data with other research groups in other parts of the world, and those entities would not be covered by CCPA either.”

Privacy and the First Amendment

The right to use photos or videos of individuals for facial recognition goes back to the First Amendment, Gidari said. “There can be no privacy invasion in a public place or its subsequent publication,” he wrote, summarizing Louis Brandeis’s influential 1890 Harvard Law Review article “The Right to Have Privacy.”

Distributing or manipulating an image taken in a public setting similarly falls under First Amendment protections. “I am entitled to repeat what I have seen, including by means of sharing photographs, an act of speech as well,” Gidari explained.

“Facial recognition is simply a mathematical representation of the image,” he added. “If you can take the photograph, seemingly you can derive other works from it by creative manipulation, digitizing it, colorizing it, and even turning it into an image map. As it is your property, your copyright, you ought to be able to then disclove it, sell it [or] distribute it for free.”

The laws governing the use and distribution of images for facial recognition were created before much of the technology existed, and Gidari noted that they’re beginning to change in response to the AI algorithms that are now starting to emerge.

He pointed to a 2013 court ruling which held that a non-economic benefit may be grounds for legal grievance. The decision holds that the “common law cause of action may be stated by pleading: the defendant’s unauthorized use of the plaintiff’s identity; the appropriation of the plaintiff’s name, voice, likeness, signature, or photograph to the defendant’s advantage, commercially or otherwise; and resulting injury.”

Beyond Stanford, facial recognition technology has quickly developed into a hot button issue.

San Francisco, home of the BrainWash cafe, banned the use of facial recognition by city departments in May 2019. “[Facial recognition] is a uniquely oppressive tool in as much as people cannot really hide their faces in public,” said Lee Hepner, legislative aide to Supervisor Aaron Perskin, who sponsored the bill. “It’s the dream of people who have been invested in a surveillance state for the better part of a century.”

Facial recognition and policing

Beyond research practices, much of the concern over facial recognition stems from the inaccuracies and racial biases of the technology. “Studies have taken place that show that [it] disproportionately misidentifies women and people of color,” Hepner said. “One of the reasons why this [happens] is because in large parts it’s been developed and tested … on groups of white men.”

Racial bias in facial recognition was a factor in the California State Assembly’s decision to enact a three-year facial recognition police ban. In one study, Amazon’s facial recognition software, Rekognition, incorrectly matched 26 state legislators — including Ting — with criminal mugshots.

“Many of the other legislators with false matches are also people of color,” Ting wrote in an email to The Daily.

Amazon has criticized the Rekognition study, citing the fact that the software’s confidence threshold for a match was set at the default level of 80% instead of the recommended 99%, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

“At this point in time, the technology is still too flawed to discuss under which narrow circumstances, if any, that the technology should be used,” Ting wrote.

When used as a law enforcement tool, facial recognition’s errors can have disastrous consequences. “In instances of misidentification, it can be a life or death scenario,” Hepner said. “We saw this with a woman named Denise Green. She was pulled over and held at gunpoint for [20] minutes. It was because a license plate reader misidentified her license plate.”

Recent protests over police treatment towards Black citizens has further prompted the private sector to reconsider its relationship with facial recognition technology. Amazon recently voluntarily instated a one-year ban on police use of Rekognition. IBM has also said it will halt the sale of its facial recognition technology, and Microsoft has vowed to hold sales until a national law passes that will regulate facial recognition.

Even if the technology does improve, Ting is wary about its use by police departments. There’s no “magic number” or performance target that he sees as sufficient to allow it. “If a law enforcement officer is walking down the street wearing a body camera with facial recognition, it’s akin to requiring [that] every person who passes that officer provide identification without cause,” Ting wrote to The Daily.

Cagle is similarly skeptical about the use of facial recognition by police departments. “It’s important to remember that surveillance is not an easy fix to public safety issues,” Cagle said. He referenced the San Francisco ban on facial recognition as a model of community engagement. “What’s really happening in San Francisco is that the policymakers are listening to residents who are saying, ‘Actually, we do not think a new invasive surveillance technology is going to make us safer.’”

In addition to preventing the police use of facial recognition, the San Francisco ordinance requires all city departments disclose how they’re using surveillance technology. “The idea is to allow the public a window into how their information is being collected, how their personal information is being used,” Hepner said.

He added, “One of our goals by compelling departments to disclose every piece of surveillance technology that they own or use, and how they use it, is to provide useful information for policy makers to make critical decisions about how people’s personal information is used or how these technologies are being used for the public benefit. That’s all useful information for my boss to know, [and] for all elected officials to know.”

The disclosure rules helped shed light on some unexpected uses of surveillance technology. In one case, San Francisco’s Public Utilities Commission (PUC) disclosed the intended purchase of $17 million worth of streetlights equipped with audio and video sensors, according to Hepner. “That raised a lot of eyebrows,” Hepner said. “Why are we equipping our street lights with audio and video capabilities?”

He added, “The PUC did not ultimately have a really great response to that [question].”

The streetlights were set to be placed in the Tenderloin district, a historically low-income community. “Why are we putting these in the Tenderloin?” Hepner asked. “That question never really got aired out in public. But I think that the implications around targeting a community that is proportionately low-income is troubling.”

While many private companies have paused the sale of facial recognition software, there are few national or state laws regulating its creation, or the collection of the photos and videos necessary to train it.

“It’s easier for us, as a regulatory matter … to get our own shop, our proverbial house in order, than it is to regulate private use of technology. And we’re often preempted in that latter category,” Hepner said.

As politicians and communities continue to grapple with the role facial recognition and surveillance should play in society, Stanford’s own place in that debate warrants reflection. The public hearings and open nature of political discussions around facial recognition contrasts with Stanford’s response. The three authors of the 2015 paper — Ng, Stewart and Andriluka — all declined to comment, as did the University IRB, Office of Information Security and Privacy Office.

When Stanford researchers pulled video of a few dozen cafe patrons in 2015, facial recognition training data wasn’t yet making national news, and neither lawmakers nor local communities had begun to fully grapple with the ethical implications of the powerful new surveillance technology. But, through a quirk of historical circumstance, only a few blocks separated the BrainWash cafe (which closed a few years later) from the intended site of the PUC’s audio and video recording street lamps.

Though the lamps wouldn’t have drawn from the same algorithms as those honed on Brainwash footage, they do both testify to the same underlying phenomena: increasingly prevalent and sophisticated surveillance technologies, the likes of which are being developed only a couple dozen miles to the south, often among Stanford’s own palm trees and sandstone arches.

Contact Nicholas Midler at midler ‘at’ stanford.edu.