Over the second half of 2020, I will be attempting to read one book a week from a list the Strategist curated by asking upcoming authors to recommend books they have turned to for solace during the present pandemic. Three weeks ago I reviewed “The Lonely City” by Olivia Laing. Since then, I’ve gotten through Kent Haruf’s “Our Souls at Night” and Brad Watson’s “Miss Jane.” This week I’m writing about J. D. Salinger’s “Franny and Zooey.”

J. D. Salinger’s “Franny and Zooey” presents two short stories that examine the course of an existential crisis triggered by the teachings of a mysterious spiritual book. Although this recent book is the last straw launching Franny into her breakdown, the internal conflict leading her to that moment has its roots further back in the past. Franny belongs to the fictional Glass family, developed by Salinger through a series of short stories published in The New Yorker between 1948 and 1965. The seven children of this family have all starred in their respective times on a radio quiz show titled “It’s a Wise Child.” A childhood spent cultivating marketable intellect has left these children with a virtually unending repertoire of academic knowledge.

The education of the younger children has been heavily influenced by the two oldest, Seymour and Buddy. The latter have sought to hold back the knowledge of “lower, more fashionable lighting effects — the arts, sciences, classics, languages” until Franny and Zooey, the two eponymous and youngest siblings, are both “at least able to conceive of a state of being where the mind knows the source of all light.” As a result, Franny and Zooey are acquainted with philosophical and spiritual ideas from around the world at a very young age. This creates a sort of intellectual burden, especially on Franny, as she comes to know an immense amount about how one might live a good life without knowing how to apply this knowledge to her own life.

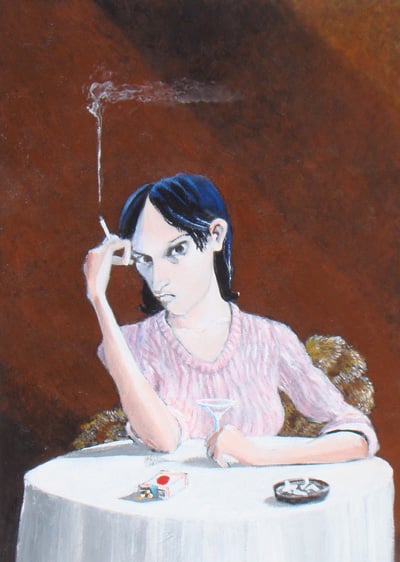

Due to her immense academic knowledge, she is able to critique virtually any intellectual idea but often contradicts and critiques herself in ways that devalue her intellect and make her seem pretentious. Through the book we see her hypercritical nature — a severe disillusionment, constant wariness and the inability to even maintain conversation with her boyfriend, Lane, without talking down to him in some way — start to affect her physically. Her lunch date with Lane works her into such a state of agitation that “Franny,” the first of the two short stories, ends with her fainting at the restaurant.

The second story, “Zooey,” shows Franny sitting on a couch, reciting a prayer she found in the aforementioned mysterious book, barely eating, shunning any affection or uplift and wallowing in what is shown as an almost egoistic, partly contrived form of distress. We then get to meet Zooey, who himself bears some of the burdens of over-education and seeks to remedy Franny’s situation through a variety of arguments and approaches.

At first this seems like just one of a host of books talking about the effects of disillusionment on the youth. At further examination, one sees the small details that lend the disillusionment and distress in this book a greater degree of depth. A prominent instance of this is Seymour’s (the oldest brother’s) not-so-recent suicide. The fact and manner of his death is fairly explicit but one must read between the lines to see the extent of its effects on the Glass family.

A closer read suggests that part of Zooey’s franticness in his attempts to console Franny must derive from a fear that Franny is headed down a depressive path that may lead her to hurt herself like Seymour did. It also reveals how the Glass family has lost not just an elder sibling but also a spiritual mentor. The second eldest, Buddy, while alive, is distant from the family. He refuses to purchase a phone for himself and is regularly out of the reach of his family. In the absence of Seymour and Buddy, Franny and Zooey seem like mere children handed complicated thoughts that they cannot meaningfully process or internalize.

We explicitly see how dependent the two youngest siblings have been on Buddy and Seymour for guidance when Zooey, having himself failed to improve Franny’s state of mind, asks her if he should try getting Buddy on the phone. This dependency is further highlighted when, as a last resort, Zooey pretends to be Buddy in order to get through to Franny. This works for a bit, and shows Zooey using his love for acting to help his sister out, but the siblings know each other too well and soon Zooey says something Franny knows only he could’ve said.

There is a fair bit of back and forth between the two throughout “Zooey,” but he does eventually succeed in lifting Franny out of her depressive episode. This is accomplished through their reminiscing over the shared memory of Seymour coaching them during the days of “It’s a Wild Child.” He’d often need to motivate them to be fully present in the show. Zooey draws on these experiences to motivate Franny to be proactive and present in her adult life. In this final cure, we once again see the crucial nature of an older spiritual mentor for Zooey and Franny.

The ending is kind of heartwarming. I like things coming full circle. I like the fact that a memory of the same person whose loss contributed to Franny’s breakdown in the first place brings her back. Full-circling aside, I cannot help but think of how familiar the themes and issues of this book felt to me as a politically active Stanford student amidst a global pandemic in 2020. This familiarity ran on several levels.

In the most basic sense, Stanford brought to me a sense of disillusionment similar to Franny’s. In my freshman year, I found myself surrounded by peers whose instinctive reaction to absolutely anything was to look for ways in which it could be wrong. Their criticism wasn’t always uncalled for, and a healthy ability to independently critique is part of what I hope to develop through a liberal education in the States. The new critical framework I picked up on did, however, often reach an extreme where I wondered if there was anything that was ever capable of being entirely free of criticism in some way or the other. Put this in the context of my general tendency to be highly optimistic, and you get a fair dose of unwanted internal conflict.

The pandemic then proved to us that worst case scenarios do come true. I remember telling my friends in late February, when I was just beginning to hear of COVID-19, that diseases come and go and that they shouldn’t worry — that this would all be gone by the time Spring Break rolls around, and we shouldn’t cancel our trip to LA. I remember once again in May, when India started opening up for the first time, thinking it’d be safe to meet friends in July. Mid-August, we are no closer to the end of this than when it all began.

This repeated disappointment has made me and those around me not just skeptical of COVID-19 projections in particular, but of the institutions that are supposed to protect us as a whole. Stanford and ICE and the Indian government all, in their own multitude of ways, have messed up, and I am now beginning to see the more permanent, disillusioning effects of this series of events. When the ICE regulation was struck down due to a nation-wide uproar from top universities, we found ourselves saying universities only helped because tuition was on the line. International tuition is important to universities, but that shouldn’t mean (or so I personally think) that we are unable to celebrate any win without a ‘but’ hanging around the corner of every sentence.

I have no doubt I am not the only one thinking about these things. The transformation of Stanford Missed Connections (SMC) from a place of romantic long shots to a place of political conversation is very telling. SMC has turned into a constant source of information about the ways in which different things I didn’t know were wrong are actually wrong. And I love knowing these things, but I cannot help but wonder where one draws the line between critical and over-critical. And there are days when arguments and counter-arguments make me want to crawl into a hole and protect myself. I don’t think we ought to be able to shield ourselves from the harsh realities of the world, but I find myself in that hole more days than I like, and cannot help but wonder if I might visit less frequently if our online discourse was less critical and more reparative.

So that’s the basic level at which I feel like this book applies to our modern, mid-pandemic collegiate lives. The other way I see myself in “Franny and Zooey,” and “Franny and Zooey” in me and in my community, is in our being burdened by excessive philosophical and spiritual knowledge. I don’t think there’s anything inherently harmful about information itself, but an inability to sufficiently integrate information — a failure to convert it into wisdom — can be the source of a great degree of distress.

A particularly striking example of this lies in the domain of self-interrogation and self-awareness. Most people I surround myself with are extremely aware of toxicity that harms either others or the self. We often introspect and discover one cognitive distortion or the other within ourselves but are unable to act upon these realizations in a productive way.

For instance, while taking a writing class in the spring, I realized my affinity for objectifying myself through hookup culture comes from a place of deep insecurity, from a need for social acceptance and to establish myself as something other than a ‘nerd.’ I have held this realization for over four months but have still, in quarantine, found myself on multiple occasions craving the instant validation of casual sex.

So on the one hand, we have instances where we know what we ought to change, but not how to change it. On the other hand, we have instances where we urge others to live better lives but refuse to do the same for ourselves. We check other’s bedtimes and make sure others are eating properly without any regard for our own health. We create space where others can let down their walls but resist showing vulnerability ourselves. We disseminate kindness but cannot see the same beauty we see in others when we look within.

I’d conjecture that this repeated pattern of self-deprecating and self-harming double standards is a direct result of a lack of effective guidance and mentorship, similar to that faced by Franny and Zooey. I suppose the positive in this is that if one takes this parallel to be true, then Salinger’s work offers us a clear way forward. The novel, along with Franny’s breakdown, ends when Zooey implores her to express empathy in her critique, and to stop being so stuck in ideas; to act with excitement and vigor and to do so religiously, regardless of the fact that there is some way to critique anything that anyone might do — particularly her acting, which may be viewed as a specially egoistic endeavor. He implores her, with help from their shared memory of Seymour, to abandon the nihilism that often accompanies disillusionment.

“I sound as if I’m undermining your Jesus prayer,” Zooey says in the midst of a tense dialogue with Franny. “And I’m not, God damn it. All I am is against why and how and where you’re using it. I’d like to be convinced — I’d love to be convinced — that you’re not using it as a substitute for doing whatever the hell your duty is in life.”

This ending on Salinger’s part calls for greater conversation, for embracing external guidance and ultimately for more kindness and courage in all of our endeavors, whether they seek to improve externally or internally. So to anyone in any degree of existential crisis, I will recommend this book in the hope that it may act as a rough reminder that wonky philosophy and hypercriticism and self denial accomplish nothing if we are not able to forward our own lives in meaningful, fulfilling ways.

Contact Smiti Mittal at smiti06 ‘at’ stanford.edu.

This article has been corrected to reflect that J.D. Salinger’s short stories on the Glass Family were first published in The New Yorker. A previous article misstated that they were published in The New York Times. The Daily regrets this error.