Don’t blindly trust (Stanford) emails

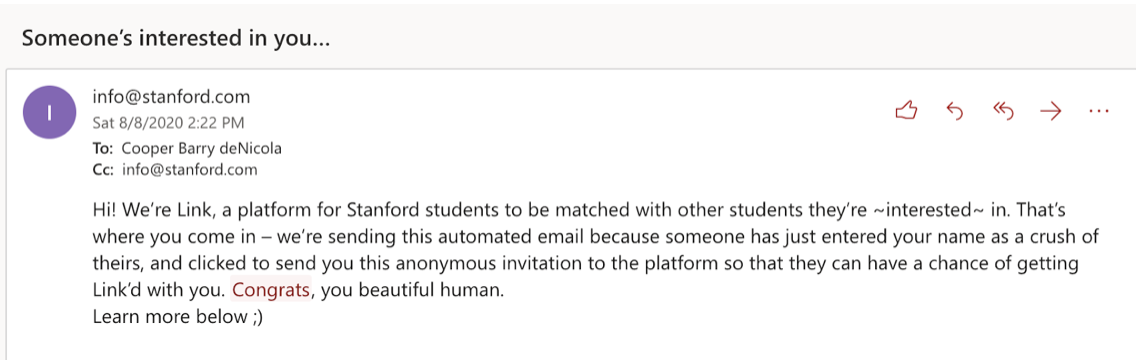

An email entitled “Someone’s interested in you…” from [email protected] appeared in my inbox. Confused by the subject line, yet expecting important information from Stanford’s information service, I cautiously clicked. My inquiry was quickly greeted by a thinly-veiled advertisement for a freshly hatched dating website focused on linking Stanford students.

My inbox marked this email to originate from Stanford, yet the message’s content was clearly closer to a ferocious phishing campaign than critical University information. At first glance this email may appear to be from Stanford, although looking deeper into the email’s header information, I discovered that it was sent from an unrelated website merely pretending to be Stanford.

Stop spoofing with DMARC

Anyone with the right tools and technical knowledge can send out an email that appears to be coming from a Stanford email address — any Stanford email: mine, yours, MTL’s and even the admissions office’s. Emails being sent from a falsified domain is called spoofing, and the origin of this problem goes back to the creation of email, which was designed to mirror real-world mail to a shocking degree. In the same manner that I could send you a letter and write another person’s return address on it, I could send you an email disguised as being sent from someone else. Email was not originally designed to verify that an email’s sender is who they claim to be.

This is, quite clearly, a problem for large companies, email providers and individual users. The lack of sender verification in emails is often abused in phishing attacks, which are fraudulent attempts to obtain sensitive information by pretending to be someone else. To solve the spoofing problem, Domain-based Message Authentication Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) was created in 2010. Using DMARC, a domain (the portion after the @ sign in an email; i.e., @stanford.edu) can set up a policy to reject, quarantine or simply monitor emails spoofed from their domain. This works by publishing the policy for a given domain onto their DNS record, so that a receiving web mail server (Gmail or Outlook) can check it against the sending domain’s DMARC to verify that the email really came from that domain. Stanford can help prevent their emails from being spoofed by setting up a DMARC. This can greatly reduce the potential of what has previously been a very successful avenue of attack.

The DMARC information for stanford.edu shows “No DMARC Record [is] found.” Source

Cyber security is a rapidly-evolving field where adversaries are adapting their methods just as fast as we can respond. While DMARC can help prevent spoofing emails, it is not a magic bullet capable of securing your emails at the touch of a button. A well-defined DMARC could greatly reduce emails spoofed from Stanford’s domains, but there are other avenues through which phishing attacks can be launched.

Detection to prevention

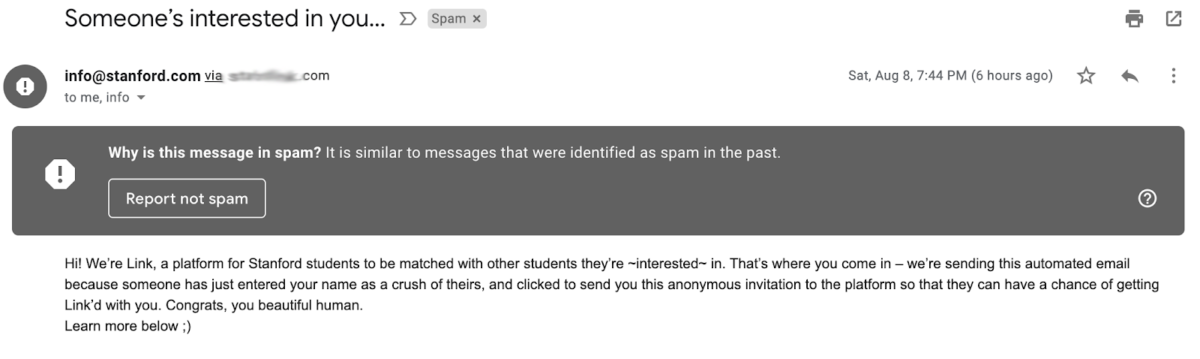

Mail servers can be configured to help detect and prevent malicious content before it ever reaches the user. While the default Outlook inbox provided by Stanford does not give a user any indication that the email is from a falsified sender, the same email received in a Gmail inbox indicates the email was sent from “[email protected] via [another website].” Gmail caught the email as spam — giving the reader some indication that the email may not be what it claims to be. Given Stanford’s current setup, unless some aspect of the message is suspicious enough to cause a reader to inspect the email header (in this case, the odd subject line), there is no warning that the sender is not who it claims to be.

An email spoofed from [email protected] appearing in Stanford’s default Outlook mailbox. Notice that this is identical to a legitimate email. Cropped out of the email are three URLs pointing to a non-Stanford website.

An email spoofed from [email protected] appearing in Gmail’s default mailbox. Notice that the email was caught as spam and the ‘from’ attribute includes “via [another website],” indicating to the reader that something is suspicious. Cropped out of the email are three URLs pointing to a non-Stanford website.

What does this mean for you? Most importantly, it means you cannot blindly trust emails you receive — and that includes emails from a Stanford address. The University currently offers neither the protections needed to catch spoofed emails before they reach our inbox, nor the capability to detect them once they are received by us. In this case, the spoofed Stanford email is the result of a non-malicious effort to launch a student social platform. While this may seem harmless, the use of a spoofed Stanford email enables the sender to collect user information by piggybacking on Stanford’s reputation.

The risk

Let us turn our attention towards a more serious adversary with intention to harm. Imagine an attacker posing as Stanford’s financial aid office with a legitimate-looking email that asks students to fill out a financial form. This attack could trick students into giving away valuable personal and financial data. Another example of the risk spoofing poses would be if every student was informed through a mass spam email from [email protected] that they were potentially exposed to a dangerous disease. An email like this could cause widespread panic among students. Spoofed emails can cause real harm in people’s lives.

Stanford has historically been a target of both regular attackers and foreign intelligence agencies looking to steal intellectual property and cutting-edge research. The University was so concerned about phishing attacks that in 2016 the University’s IT department created the Phishing Awareness Program to train University staff on how to recognize and avoid phishing attacks. Yet as recently as this March, a single phishing campaign utilizing a spoofed Stanford email compromised over 150 Stanford accounts. Asked about available options for students to protect themselves, Ernest Miranda, the University’s senior director of media relations, said the University is beginning to pilot their program to students, who can request access by submitting a Service Now ticket.

In addition to their pilot program, the University could increase user security against phishing by stopping email spoofing on their domain, offering warnings when an email is received via an unexpected source (similar to what Gmail does) and expanding their Phishing Awareness Program to create an educational program that teaches all students how to protect themselves against malicious emails.

All this being said, it is ultimately the responsibility of the user to protect themselves online.

Protecting yourself

The more informed one is, the more careful one can be. This is not to say that every email is a lie carefully curated to steal your passwords and personal sanity until your online identity is open-sourced. However, as with any interaction with the wild west world of the world wide web, you must maintain a constant level of caution and vigilance. On the internet, URLs do not always go where they claim to go and a website that appears harmless at first glance may be trying something malicious behind your back. Anything that feels “too good to be true” probably is.

It is understandable that constant vigilance is hard to maintain, so if you want a general rule of thumb for email security, keep these four principles in mind:

- If an email is asking for your personal information, immediately be distrustful. Ask yourself: Why do they need this information? Could an attacker use this information? What could I lose if this information gets out? According to RiskIQ, every minute, $17,700 is lost due to phishing attacks. Protect yourself by being cautious online.

- A link in an email can take you anywhere on the internet, so always be careful when accessing a website through a link — it may take you somewhere you did not intend to go. Before you click a link, hover over it to see the URL to which you are actually being redirected. If possible, navigate to the expected website by typing the URL directly into Google instead of clicking the link, so that you are certain you reach the intended site. And if you do click the link, always look closely at the address bar to make sure it is the site you expected, and not a disguised lookalike with a similar domain — if it’s not correct, close the tab immediately.

- Do not blindly open unexpected email attachments, as CSO Online reports that 94% of malware is distributed by email. If the email topic does not appear to require an attachment or you do not recognize the sender, then you might be better off leaving it unread.

- Lastly, Miranda reminds us “to recognize that phishing is about social engineering and social engineering is about emotions and manipulating them to get an individual to do something they would not normally do. Some of the most effective phishing attacks do not involve links or attachments but they leverage emotions such as fear, greed, desire to please and sense of urgency. Recognizing when your emotions are being manipulated and how to properly react is a very useful skill.”

As members of the Stanford community, you have access to additional resources to keep you safe.

- If you receive an email you suspect is phishing, forward it to [email protected] to help the University’s Information Security Office filter bad emails and protect students. Using reported emails, Stanford University IT keeps a catalog of recent phishing schemes that have jeopardized affiliate accounts. The list can be used to familiarize yourself with recent attacks.

- The University offers several classes with expert professors that discuss computer safety and security. Join INTLPOL 268: Hack Lab (where I am a course assistant) in the fall, CS 152: Trust & Safety Engineering in the winter or CS 155: Computer and Network Security in the spring to learn how to protect yourself and others on the web.

- Use a password manager to create a unique password for each account. That way, a data breach that steals your credentials for one account cannot be used to access other accounts. Stanford offers a free Dashlane Premium account to all University affiliates.

Contact Cooper de Nicola at cdenicol ‘at’ stanford.edu

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to eic ‘at’ stanforddaily.com and op-ed submissions to opinions ‘at’ stanforddaily.com.