“Overtime” is a series documenting the reactions of field hockey alumnae to the University’s announcement on July 8 that Stanford Athletics would discontinue the sport and 10 others after the 2020-2021 academic year. Part one on initial reactions and the petition can be accessed here.

For many academically driven athletes, Stanford is a dream school. The University is arguably the best overall program in the NCAA, having won the last 25 Director’s Cups, and also consistently ranks as one of the top universities worldwide.

“I chose Stanford due to its combination of excellent academics and athletics,” said Christina Williams Harding ’03 M.S. ’04, a former midfielder and former Stanford assistant coach. “Stanford clearly distinguishes itself on modeling how to be an ideal scholar-athlete, and that is crystal clear when you come to visit campus — whether on a recruiting visit or otherwise.”

With Stanford field hockey discontinued, however, many high school players will no longer have the opportunity to play for the Cardinal, cutting short or altering the dreams of many young players.

Former defender Kelsey Scherer ’15 now coaches a club field hockey team in St. Louis. One of her teenage players recently verbally committed to Stanford but will now have to rethink her collegiate plans.

Scherer was tasked with relaying the news of the cancellation to the rising high school junior since recruits were not invited to the Zoom announcement.

“She was just in tears,” Scherer said. “It’s her dream school with her dream program. Now she has to decide, does she give up the sport that she absolutely loves to go to the university that she wants to go to? Or does she start over? It’s heartbreaking.”

Another affected recruit is the daughter of former player Maree Chung ’87. Despite the cut, the incoming freshman is still planning to attend the University to play for the program’s final season, which has been postponed until spring due to COVID-19.

“It has never occurred to her to go anywhere else, and she was so excited,” Chung said. “Right now I just keep saying to her, ‘We’re going to try to get [the program] back’…I feel like we have a chance.”

Modeling diversity in multiple ways

Among the reasons for the intended cancellation cited in the University FAQs are the limited number of NCAA teams on the West Coast and “impact on the diversity of our student-athlete population.”

Field hockey is largely an East Coast sport at the collegiate level, and Stanford is just one of three Division I programs in the West. But alumnae argue this should be a reason to keep the team, not to cut it.

“When Stanford does anything, they’re a thought leader, they’re an influencer, and it messages to the West Coast community that this is something that’s important,” Bassi said.

Given the University’s status as a leader, alumnae said that the success of the Cardinal team has fueled the creation of new field hockey programs for younger players throughout the region. Without the prospect of playing for Stanford at the collegiate level, however, movement away from field hockey may also occur at lower levels.

On the collegiate level as well, the discontinuation of net-negative revenue sports at Stanford may send a message to other collegiate athletic departments that they should also pivot their focus to sports that bring in revenue.

The National Team typically draws its players from the East Coast as well. Twenty-two of the current 23 USWNT members hail from the East Coast; the only non-East Coast native is Kelsey Bing ’20, the three-time America East Goalkeeper of the Year goalie from Houston.

Similarly, Scherer said that when she played for the National Team in 2015, she was the only athlete who did not grow up on the East Coast.

Many field hockey athletes who grew up on the West Coast — including Scherer, a San Diego native — said their passion for growing the sport on the West Coast was a factor in their decision to play at Stanford instead of an East Coast college.

Former attacker Kristina Bassi ’17, raised in Mountain View, grew up attending Stanford athletic events, particularly women’s basketball and soccer games. Cardinal student-athletes, like women’s basketball’s Candace Wiggins ’08 and Jayne Appel ’10, were “icons” to her.

“Knowing that Stanford had a [field hockey] program was like a lighthouse for me,” she said. “I was like, ‘This is where I want to go. I know this is something that can give me more opportunities.’ When it became a reality my junior year of high school…it was a dream come true.”

Bassi still resides in the Bay Area, where she coaches a non-profit field hockey club.

Aside from regional diversity, alumnae also emphasize the other types of diversity on the team. Stanford Athletics’ vague wording prompted some alumnae to question how exactly the University defines “diversity.”.

“What is diversity?” Chung asked. “Is diversity only a certain race? When I played, the field hockey team had a lot of diversity with the [LGBTQ+] community as well, but that was [seemingly] not considered. Is there only one classification [of diversity]? To say that these sports didn’t represent diversity for the school was very confusing.”

When asked for further comment, a Stanford Athletics spokesperson wrote, “Stanford is committed to creating a diverse and inclusive campus community, and that includes the Department of Athletics. As we evaluated these changes, we placed a high priority on preserving the diversity of the overall student-athlete population. The decision to discontinue these 11 sports will not disparately impact any particular demographic.”

Field hockey, however, is one of the more internationally diverse teams at the University. Nearly 30% of the current roster hails from outside of the United States — including three players from England, one from Canada and one from South Africa. By contrast, the undergraduate student body as a whole is only 11% international.

Club sports: A viable alternative?

Stanford’s club sports program currently offers 32 options for current students, and that number will likely grow after 2021 since “all of the [discontinued] sports will have the opportunity to compete at the club level after their upcoming varsity seasons are complete,” according to the University’s official announcement.

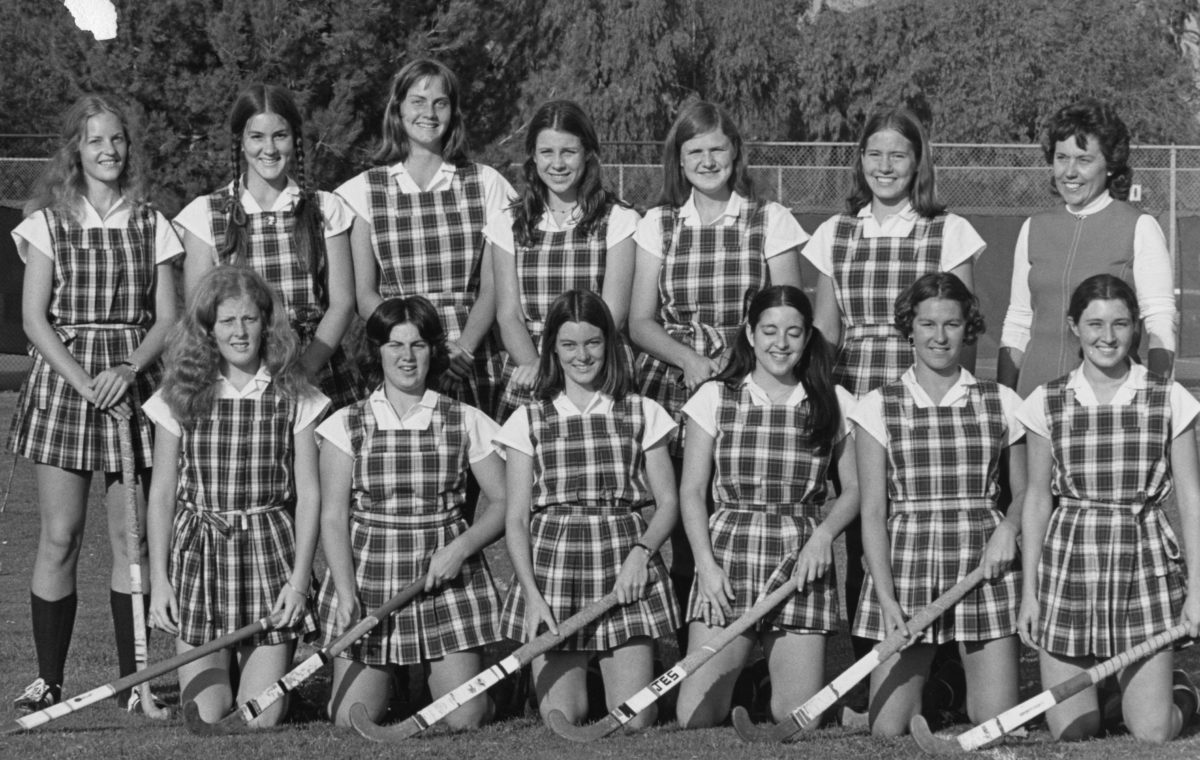

This is not Stanford’s first attempt to move field hockey down to the club level. A similar plan was proposed in 1990, and it also garnered negative reactions from players and alumnae.

Caroline Clevenger ’91 Ph.D. ’10, who played on the field hockey team, wrote an open letter to The Daily in 1990: ‘Demoting field hockey to club sport insults players.’ She ridiculed the Athletic Department’s assertion that club sports are nearly identical to varsity sports, writing that “if the caliber and intensity of varsity and club sports are the same, why doesn’t the Athletic Department demote every sport except the money-making enterprises to club status and everyone, the players and the administrators, could be happy?”

Now, similar sentiments persist. Other alumnae expressed similar concern with the level of competition of club sports, stating that to improve as a player and to be able to move on to the next level, competing against top competition nationwide is crucial.

Competing against top teams from the East has been a yearly staple for the team, but the shift from varsity to club will limit the level of competition and opportunities for travel.

“For a program to be successful and competitive athletes to really want to go there and pursue their athletic and academic careers,” Scherer said, “it has to be a Division I, NCAA-recognized sport.”

Bassi, however, noted that there were some positive aspects of club sports.

“I think club sports are a good path forward for the future of sports in general,” she said. “I do think converting sports into club sports and thinking about creating this more holistic, accessible sports experience at universities is really positive. It would be horrible if these sports remained cut and they didn’t get an opportunity to turn into a club.”

Success across the Bay

The planned elimination and eventual reinstatement of five varsity sports at Berkeley during the 2010-2011 academic year provides a beacon of hope for the Cardinal.

In September of 2010, the University of California announced that it would eliminate men’s and women’s gymnastics, baseball and women’s lacrosse, while demoting men’s rugby to varsity-club status. Citing the rising cost of athletics departments, unforeseen financial consequences brought on by the Great Recession and state budget cuts to the university, Berkeley eliminated those sports in an effort to save close to $4 million annually.

Cal initially did not believe it was feasible for its community to raise sufficient funds to reinstate the programs, saying at the time, “It would be unrealistic to expect a significant number of donors to immediately increase their giving far above current levels.” However, by May 2011, all five sports had raised sufficient funds for official reinstatement — nearly $25 million across the teams. Ultimately, Berkeley reinstated all five programs at the varsity level.

Because Cal gave set monetary targets for the sports to reach before they could be reinstated, it gave students, alumni and other supporters a specific goal for their fundraising efforts. By contrast, Cardinal field hockey alumnae noted that the lack of transparency surrounding Stanford’s financial situation makes fundraising and the eventual reinstatement of the team even more difficult. Unlike Berkeley, Stanford Athletics has not announced monetary targets for the teams to reach before each team can be reinstated. Instead, the University wrote “any future philanthropic interest in these sports may be directed towards supporting them at the club level.”

“The [Cal] community needed to understand that they had certain goals that needed to be met,” Williams Harding said. “The community didn’t understand that before, and the cuts allowed them to understand the seriousness of the situation.”

In spite of Stanford’s refusal to accept funding for the varsity program, the Cardinal field hockey community is in the process of raising sufficient funds to cover operating costs for the team indefinitely in an effort to convince the University to allow the sport to continue to operate at the varsity level. “I truly believe that the [Stanford] administration can be transparent with those clear targets,” Williams Harding said. “Teams will work tirelessly on a solution to meet those goals. It seems completely antithetical to Stanford’s values to not be given the chance.”

Despite unclear financial goals and Stanford’s insistence that the cancellations are final, alumnae refuse to go down without a fight.

“Stanford created monsters,” Scherer said. “They created these strong female athletes [and gave them] an amazing experience. They’ve now created young women that are smart, resilient and do not give up.”

Contact Sofia Scekic at sscekic ‘at’ stanford.edu and Mary Lee at marylee1099 ‘at’ gmail.com.