It is a warm August afternoon, and Sarah Puckett is in her classroom at Brookside Elementary in Marin County — like she is every year before the first day of school, setting up for the incoming first-graders she will soon get to know.

But this year feels different. There is no excitement of back-to-school shopping, of planning the perfect first-day-of-school outfit, of handwritten name tags placed on desks with care.

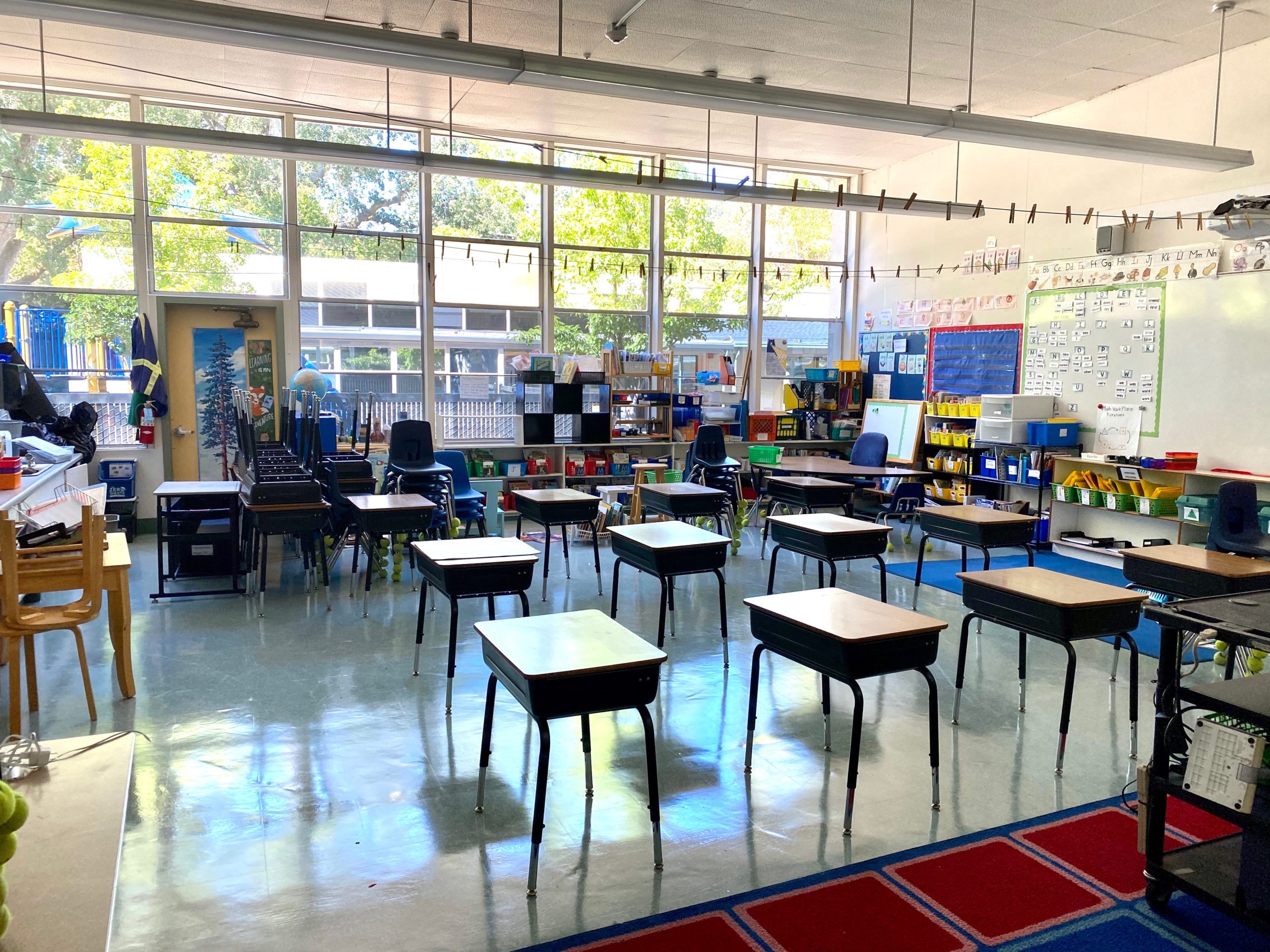

Instead, Puckett arranges desks six feet apart in case students can return to class in person, sanitizes everything in the classroom and prepares a Zoom video conferencing link, knowing that this school year will be unlike any other.

Amid rising coronavirus cases, the question of whether schools should reopen remains at the forefront of students’, teachers’ and parents’ minds. Teachers, in particular, are the ones on the front lines when schools reopen.

Despite the risks, Puckett finds it “so important for kids to be in-person learning. As long as everyone understands the safety protocols and puts on their masks and everyone stays six feet apart, the benefits of in-person learning outweigh those small risks.”

Puckett’s opinion of the importance of an in-person education is shared by an anonymous first-grade teacher at a Bay Area private school, who believes that the young age of her students hinders them from learning adequately online.

“I feel it is the best option for me and my students because I’m a first-grade teacher,” the teacher said. “I don’t feel as if [Zoom] is a fit for the younger kids, but I also understand that it’s a personal choice among parents, too, and if they’re comfortable with sending their children.”

Chizzie Brown, an English teacher for ninth, 10th and 11th graders at High School 1327 (a temporary name after the original name, Drake, was removed due to Francis Drake’s connection to the slave trade), disagrees, believing it safer and easier to focus solely on online learning rather than start in-person, then potentially having to revert to a distance learning model in case of a school-wide coronavirus outbreak.

“Based on what I’ve been following in the news with other states that have been going back, they’ve very rapidly closed almost as quickly as they opened,” Brown said. “That pattern of coming and going and coming and going — I think that can be pretty disruptive to learning.”

Most recently, a Georgia school district opted to start the school year in-person, resulting in the mandated quarantine of almost 1,200 students and faculty.

Brown partially attributed her opinion to the difficulty in getting high schoolers, many of whom have cars and a newfound sense of freedom, to practice social distancing. A 2020 study by Montana State University researchers surveyed 770 adolescents and found that only 31.4% were partaking in complete social distancing, even though 89.4% were following coronavirus news.

“The restrictions that need to happen in their lives in order for us to lock this thing down are a big ask for kids,” Brown said. “It’s complicated to make those demands on young adults who have cars and freedoms.”

Even though Brown has had the summer to prepare for online school, she still finds the experience stressful.

“In some ways, I’m more equipped, but in other ways, I’m still as anxious as I was when we had to do it on the fly,” Brown said. “I think a lot of teachers are straddling, ‘I’m gonna do better this time,’ and, ‘Oh my gosh, I don’t want to do this, I’m scared.’”

This sentiment is shared by many teachers, including Puckett, who, despite already knowing most of her class, is worried about facilitating student-teacher relationships and class-wide bonding.

“[Teachers are] not going to know their kids, and their kids aren’t going to know them, and that’s going to be hard,” Puckett said. “It’s establishing this relationship with a person who’s six or seven through a computer screen.”

Similarly, Puckett is concerned about those students who have trouble with online school, including students with learning disabilities or who don’t speak English as a native language.

She fears a distanced learning model will only further widen the achievement gap, revealing socioeconomic inequalities.

“I think it is so difficult for kids with learning issues or our English-language learner students — and those kids are just going to get farther and farther apart from the kids that it worked for, or who have family support or who can hire a tutor,” Puckett said. “The discrepancy between abilities is going to just continue to widen the longer we are distance learning.”

For the anonymous first-grade teacher, dwelling on the what-ifs is not an option; instead, she chooses to spend her energy planning for the year ahead.

“I’m just focused on providing what I can for them in the now and not as much worrying about what they won’t have,” the teacher said. “It’s really hard to focus on what they’re not getting — I’m focusing more on doing as much as I can for them.”

There is a bright side, however: online school allows teachers to reimagine traditional learning. For Brown, teaching on an online platform prompted her and her fellow teachers’ decision to limit online homework so students do not spend too much time on screens.

“Once they leave our class, they’ll read a book, they’ll do a journal, they’ll go for a hike or a walk and do some observations — but the last thing we wanted to do was pile on the screen time,” Brown added.

With so much about this year up in the air, Puckett reminded students, teachers and parents to respect each other, knowing that everyone is going through their own challenges.

“It’s important for everyone to be patient with each other, and remember to be kind, and remember that everyone is stressed and anxious,” Puckett said. “Have compassion, because this is all brand new.”

Contact Martha Fishburne at martha.fishburne ‘at’ gmail.com.