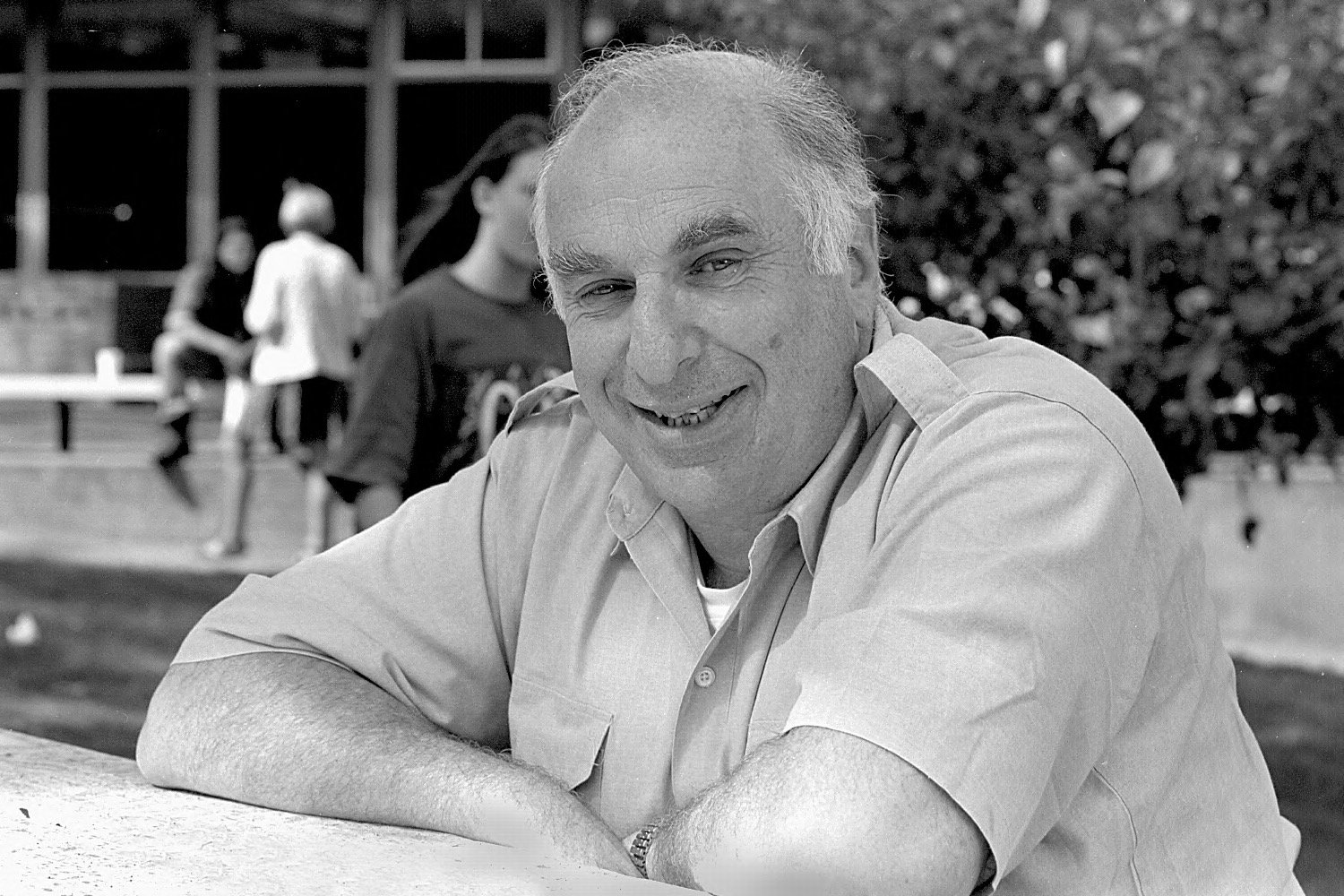

Emeritus Professor of History Mark Mancall, who revolutionized the study of the humanities by linking it with residential student life and transformed overseas studies by emphasizing intercultural exchange, died in his Stanford home on Aug. 18. He was 87.

A historian devoted to teaching across disciplines, Mancall envisioned an education that connected academics with residential life. His lasting monument is the Structured Liberal Education (SLE) program, a year-long introduction to the humanities for around 90 to 100 frosh who live and study together in East Florence Moore Hall. In his words, SLE is a “program in controlled speculation” where students engage with highly influential works drawn primarily, but not exclusively, from the Western tradition “in a rigorous fashion.”

As director of the program he founded in 1974, Mancall instructed generations of students on topics ranging from the Hebrew Bible and Marxism to postcolonial Arab literature. He taught his last class online in June.

Against the political backdrop of the early 1970s — as the U.S.’s involvement in the Vietnam War fomented widespread student unrest — former students say Mancall viewed that brand of “rigorous” intellectual engagement as not only timely, but critical. According to Jon Reider ’67 Ph.D. ’83, one of Mancall’s first students, who later co-founded SLE and served as senior associate director of admissions at Stanford, Mancall aimed not to politicize the study of the humanities through SLE, but to provide students with frameworks to answer the questions which the protests had provoked.

SLE has faced consistent criticism for its Western focus. Throughout his career, Mancall spoke to the issue.

“One of the functions of the education system is to colonize our minds,” Mancall said in his last lecture. He expressed hope that SLE would “give students the tools” to question this process — and ultimately, to defeat it.

“We wanted the students to see the faculty argue with each other, see that there was no truth,” Reider said. “The truth came out of conversation.”

Mancall had been experimenting with residential education years before founding SLE.

“You know the myth of how Zeus had a headache, and out popped Athena? Full-blown goddess, suit of armor, everything?” Reider asked. “SLE did not come out of nowhere.”

When the University booted the Phi Delta Theta fraternity from campus, Mancall saw in their empty house an opportunity. He obtained University permission to transform the abandoned building, known as Grove House, into Stanford’s first co-ed residence. Universities across the nation soon followed suit, according to Ted Mitchell ’78 Ph.D. ’83, president of the American Council on Education and under secretary of education during the Obama administration.

An intellectual theme-house occupied by students taking the same interdisciplinary seminar on social thought, Grove served as a gathering point for students and faculty. As Stanford gained international prominence as a research powerhouse, Mancall rejected what he referred to as the University’s “cafeteria style of general education,” which he thought had little regard for interdisciplinary thinking.

His academic philosophy was deeply “countercultural,” Mitchell said. “As higher education was becoming more discipline-based and more technocratic, Mark was innovating by saying, look, the most interesting things that are happening are happening in the spaces between disciplines.”

As Mancall imagined it, shared spaces and continued conversations could bridge gaps between artificial academic boundaries. Forty-six years and around 4,000 SLE students later, the experiment continues.

“Mark really was the person who turned residential education from a notion into something that was real, something that had discipline behind it,” Mitchell said. “Even though he would never have assumed this title, I think that he became the godfather of real residential learning across America’s campuses.”

Mancall’s dedication to mentorship did not stop at the classroom: Students and colleagues say they continued turning to him for guidance well after graduating. Mancall’s longevity was such that he has taught the parents of some of his most recent students.

“Mark Mancall influenced generations of students and faculty,” Hoover Institution director and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told The Daily. “When I was a young assistant professor, he was a wonderful mentor to me… He was one of those senior faculty who just knew how to put young faculty at ease — with an offer to have dinner or a cup of coffee. I was fortunate to have known him and I will never forget his intellect and his kindness.”

Countless students recall regularly crowding into Mancall’s Florence Moore apartment during his time as SLE director to watch the CBS evening news anchored by Walter Cronkite before class. After his 2007 retirement, students say he continued to leave the door open at his Stanford home. Overflowing with books, the house became a gathering place for students and teachers, world leaders and SLE alumni.

“Whenever I would go over there, somebody new was there too,” Reider said. “His cohort of people that he was connected to was endless. It was just incredible. There would be somebody who was in SLE this year, and somebody who was a former finance minister in Czechoslovakia — it didn’t matter.”

His home reflected “a smorgasbord of people and ideas,” Mitchell said. “I think for a lot of us, [coming back to Mancall’s house] was about recentering our moral and intellectual compass.”

“I didn’t really know another place where I had felt such ease being listened to,” Robert Mencis ‘18 said.

From debating questions at the heart of academia to discussing the minutiae of everyday undergraduate life, Mancall is remembered by students and colleagues for his wide-reaching curiosity and remarkable attentiveness to the lives of his students.

He was able to connect with undergraduates on topics beyond the “obviously intellectual,” said Greg Watkins ’85 Ph.D. ’03 resident fellow in East Florence Moore and SLE section leader. “There are a lot of people who got close to Mark, not because they were talking about Plato or something, but because they were hurting in some way. He was happy to have them around and help them figure that stuff out.”

Among Mancall’s “unofficial adoptees,” Reider said, was Chelsea Clinton ’01 who majored in history and later became a SLE writing tutor.

“Mancall has become a close friend for many students in serious study and relaxed pastimes such as analytically watching ‘Star Trek,’” wrote former Daily Editor-in-Chief Philip Taubman ’70 in a 1968 article for The Daily.

“When it came to teaching, he would really relish the kind of intellectual debate and really fighting it out, but at the same time, he was the kind of person who really genuinely cared about you as a human being,” Mencis said. “There’s no one else. There’s no one else in my life. There’s no one else I’ve ever encountered, who was like him.”

Mancall was born in New York City in October 1932. He was raised in Los Angeles and attended public school in West Hollywood, while his father worked on movie productions, according to colleagues. Mancall is survived by the son he adopted in Bhutan, Dechen Wangdi, and three grandsons, Kinley, Garab and Tobden.

As a teenager, Mancall aspired to be a kibbutznik — to move to Israel and “help the desert bloom,” Reider said. His parents, however, insisted he attend the University of California, Los Angeles. There, he majored in Far Eastern Languages before earning a master’s degree in East Asian regional studies and a doctorate in history and Far Eastern languages at Harvard.

One of the first 22 Americans to study in the Soviet Union during the Cold War, Mancall also studied in Finland, Taiwan and Japan. Each trip furthered his affinity for linguistics: Over the course of his lifetime, he learned more than 15 languages. Friends recall Mancall using flash-cards and an early computer program to study Finnish, Tibetan, Swahili and countless others.

Motivated to explore ethnic identities in East Asian countries, Mancall set off to Bhutan for a year-long sabbatical in the 1990s. Despite having no contacts at first, Mancall quickly transformed his Thimphu home into a nexus of people and conversation, mirroring his apartment at Stanford.

Mancall “would spend a couple hours a day in the clock tower square just talking to people,” Watkins said. “He just started building this network.”

In a 2013 interview with the Stanford Historical Society, Mancall said that upon getting off the plane in Bhutan, “within a minute, I knew I had come home in some way.”

Soon, “politicians, students, friends, people who had just heard about him” would “come and visit him, seeking advice mostly,” said Kinley Dorji, former secretary of the Bhutan Ministry of Information and Communications and a 2007 Knight Fellow at Stanford.

“His Majesty the King of Bhutan knew Mark and liked to talk to him,” Dorji said. “He was a very valuable source of knowledge and a valuable adviser and teacher”

Beyond providing informal guidance to those who asked, Mancall worked extensively in Bhutan, serving as the director of the country’s Royal Education Council and president of the Bhutan Centre for Media Democracy from 2008 to 2011, according to a Stanford News obituary. He received honorary Bhutanese citizenship in 2004.

“He was really one person I know, the only person I know, who could just be a teacher to anyone — to old, young, men, women, to people of different religions,” said Dorji, with whom Mancall also started the Druk Journal.

Students and colleagues say that this spirit of cross-cultural connection guided Mancall’s vision for Overseas Studies at Stanford. When he first took over the program in 1973, study abroad campuses were nestled away in walled-off, remote educational compounds. Mancall “canned that whole idea,” Reider said. To Mancall, study abroad meant embracing discomfort and intercultural exchange. Under his leadership through 1985, Stanford shifted overseas studies locations to urban centers, prioritizing immersion over isolation. In the United Kingdom, Cliveden gave way to Oxford; in Germany, Beutelsbach to Berlin; and in France, Tours to Paris.

Mancall also worked to establish an overseas studies program in México — he even secured a one-dollar-a-year deal from former Mexican President Luis Echeverría for an expansive overseas campus, an offer which the then-overseas faculty committee proceeded to reject. In his Stanford Historical Society interview, Mancall attributed that decision to anti-Mexican prejudice.

Prior overseas programs “have been incredibly Eurocentric,” Mancall told The Daily in 1974. “You can only stick your head in the sand for so long.”

“Mark was clear that [study abroad] was an experience that was about cultural exchange. It was about learning new things, about feeling uncomfortable,” Mitchell said. “It really helped lots of institutions figure out how to make an overseas studies experience more consistent with the intellectual mission of the institution.”

With regard to Stanford’s own intellectual mission, Mancall was unafraid to be disruptive, according to former students. His particular brand of intellectual curiosity — one which embraced ambiguity as an opportunity to keep asking questions — sometimes caused friction. Colleagues joked that the toughest part about running SLE was “managing Mancall.”

“Mancall was always coming up with these wild ideas and doing these very strange things,” Reider said. “And nine of them were really good. And the tenth one was silly.”

In the first years of SLE, Mancall tried teaching math and physics from ancient to modern times, starting with Aristotle and eventually ending up at Heisenberg. He soon scrapped that idea, Watkins said. Mancall taught several courses on the history of socialisms — plural, because he was adamant that Soviet communism was closer to fascism than true socialism. Upon realizing students knew nothing about sex workers despite discussing them in the context of the philosophy of labor, Mancall said in his oral history interview, he invited the leader of a San Francisco sex workers union to come talk to SLE. On another occasion, Mancall said in that same interview, the French philosopher Michel Foucault spoke to SLE about the Attica Prison uprising — an event that Mancall insisted Florence Moore Hall dining staff were invited and encouraged to attend.

“There was no doctrine of Mark Mancall. There was no philosophy of Mark Mancall. And every idea he had, he turned around and criticized,” Reider said. “He was the exact opposite of an ideologue. He really thought for himself. He never stopped learning. He never stopped reading.”

Students say that in an institution intensely committed to technology and research, Mancall was a humanist. His love of learning and for others converged at education.

“He had this thing he would say, that there’s only one question. It is: How are we going to live?” Watkins said. “Nobody gets away with not answering that question.”

That Mancall’s education aimed to teach his students how to live indicated “a selflessness at the core,” Watkins said. “It’s about other people. At the core of [his beliefs] is that we need to answer this question in community.”

Above all, “he would want to be remembered as a teacher,” Mitchell said. “We probably want him to be remembered as one of the finest teachers that ever lived.”

You can listen to Mark Mancall and Greg Watkins’ podcast “A Shareable World” here.

Ari Gabriel, Noah Sveiven and Daania Tahir contributed reporting.

Contact Emily Schrader at emilycsc ‘at’ stanford.edu and Michael Alisky at malisky ‘at’ stanford.edu.