Longform is a new music column for Arts & Life, published every time I get around to writing one of these. Each article will be dedicated to exploring one “long song” in depth, as well as whatever else has been stewing around in the head of yours truly.

In a memorable scene in “The Sympathizer,” the Pulitzer-winning novel by Viet Thanh Nguyen, our unnamed narrator, a Vietnamese national, gets caught in an awkward conversation with his boss. A professor of Oriental studies, he is explaining to our narrator — mixed race himself — how the “Amerasian” is the necessary future of the Asian on Western soil. To him, the half Asian represents the possibility that “out of two can come one,” e duobus unum, a synthesis of the best qualities of Orient and Occident who will act as an ambassador of peace. The narrator suggests, “like Yin and Yang?” There is, of course, a profound irony at play here: the narrator, far from being an ambassador of anything, is a spy, sent by the victorious North Vietnamese to keep an eye on a defeated general. As the novel progresses, the narrator’s dual allegiances, to government and personal relationships, homeland and adopted country, communism and capitalism, are thrown into conflict; the body becomes the site of ideological struggle. As I watch Kanye West, caught in public self-destruction for the umpteenth press cycle, the umpteenth stunt, I can’t help but be reminded of the Sympathizer and his strife in a man who, more than anything, seems desperately out of place. Caught between forces, internal and external, far beyond his control.

The Kanye Thinkpiece has, at this point, become its own celebrated microgenre, a signifier of just how much CloutTM Mr. West has generated since his debut with 2004’s acclaimed record “The College Dropout.” But we would only hit Peak Thinkpiece in 2018, as a career in controversy finally escalated to a permanent fall from grace: that video in the TMZ newsroom that will live on in Kanye-stan (StanYe?) infamy, where the rapper doubles down on the assertion that slavery was a choice. The moment was, at best, indefensible. Writers from acclaimed author Ta-Nehisi Coates to The Daily’s own Layo Laniyan examined his history of contrarianism and took on fame, the desire for whiteness and the cult of the Great Man “genius,” seeking to uproot the cultural context and personal history that could explain the Fall of Kanye. And now we are here, two years later in what is beginning to feel more and more like the endgame as West, having left his stamp on music, fashion and social media, spirals out in his attempts to take on that last Sacred American Entertainment: politics. Likewise, the Kanye Thinkpiece has fallen into a rut. The takes have grown cold. Outside of the occasional by-the-numbers dunk on election mishaps, what is left of a once-proud cultural institution has been reduced to a single-minded focus on the artist’s bipolar disorder, or even worse, a profound apathy.

I ask my fellow writers and critics, what gives? Perhaps it is a sign of the natural fatigue of the media cycle. Maybe it has to do with the work of wife Kim Kardashian, whose July 22 Instagram Story clearly demarcated the lines of battle, a simple for-or-against affair where any coverage more in-depth than empathy is cruel (I’m being a bit cynical here — it’s more than likely that the post was heartfelt and genuine, but posts can be those things while also clearly being calculated PR). Maybe we just reached a point where we had to give up, his actions too difficult to understand, too disconnected from the Old Kanye (whatever that means) to be interrogated beyond a handwave and a prescription for lithium. But neither Kanye’s diagnosis nor his lack of medication are new phenomena: by his own account he has experienced symptoms since childhood, and spent most of his life undiagnosed, and therefore unmedicated. Certainly there is a biological reality to bipolar, but even the most bio-brained psychiatrists will concede that mental illness still exists as a social and psychological phenomenon, tied to the rest of one’s life. When Susan Sontag argues against illness as metaphor, it is only an argument at all because the reaction is so automatic — life, especially the life of an artist, is nothing if not the metaphorizing of the self. Nor is Kanye undeserving of compassion and empathy in his state; rather, I ask why it must only be offered up under the clinical restraints of the DSM-5. As though we can only afford compassion to an illness and not a man himself. If Kanye West is now suddenly rendered unintelligible, it is only because we are missing the right framework: that of bipolarity itself.

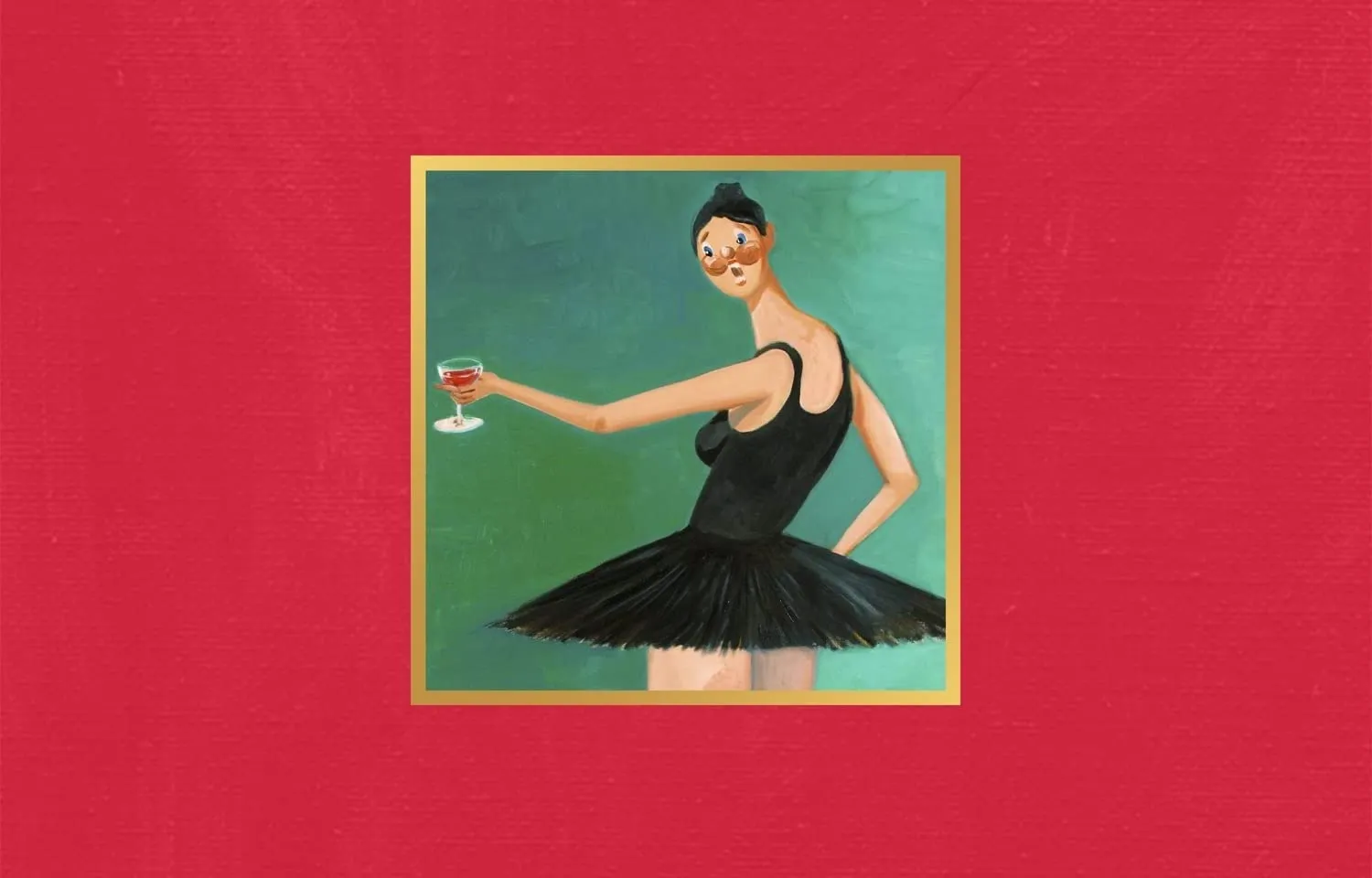

Of course on one level, the meaning of that encounter in “The Sympathizer” is about ignorance, specifically the ignorance/arrogance combo practiced by white dudes everywhere with an unparalleled art. Our narrator recognizes his boss is being, like, problematic af, but he is in no place, power-wise, to disagree. Yin and Yang becomes a joke with no audience — the narrator offers up a stereotype of his people, and in buying the performance, the professor gives us the punchline. But what’s so compelling to me about the moment is not that Yin and Yang is an inapt metaphor, but that it actually hits the nail on the head — it is just misinterpreted. Nguyen stumbles onto an essential reality of the halfie (or “lemon cream,” as I would sort of ironically self-identify as a kid) — that it is not a stable identity at all, but a dualism, a life of encounters marked on an individual basis as Asian or white. Not the resolution of halves, but a permanent split. A bipolarity. The professor applies a Western dialectic to a whole tradition of philosophy that, from the Buddhist Samsara to the Yin-Yang, denies its very existence as an illusion. The Sympathizer never finds peace in resolving the contradiction of his identities, but only by abandoning them altogether, finding (in a very Buddheo-Christian way) absolution through suffering. I am reminded of the novel once again as I watch Kanye on Jimmy Kimmel, explaining the album cover of 2018’s “Ye”: “I hate being bi-polar; it’s awesome.” As Kanye explains, it’s not an expression of opposites in stasis, a negative and a positive that resolve to nothing but instead something that “drives how you really feel” — the two positions feed one another, spinning forever. With his hands curled, he draws, in the air in front of him, a circle.

The contradictions now are too jarring, too obvious to ignore: calling for mental health awareness while rejecting the medication of mental health experts, donating millions to fight police brutality while running an election designed, ultimately, to help the party that continues to excuse and condone police brutality. But the contradictions of Kanye’s identity have always been here, and more than just being quirks or side effects of a contrarian streak they are perhaps the actual defining quality of what has made Kanye such a figure of intrigue. The duality is defined in many ways, canted at many angles: sometimes it is hometown roots versus the popstar fantasy; sometimes, personal relationships versus celebrity and ego; and yes, it is very often literally black versus white.

Watch Kanye on Def Poetry in 2003: what might be the earliest recording online of Kanye performing solo in the act of Kanye West. “All Falls Down” makes a perfect transition from rap single to slam poem, the critique more didactic, the punchlines extra punchy (as I enter the new quarter on leave, “sophomore, three years, ain’t picked a career” is now less funny and more a minor existential crisis). But the verses are swapped, so the aforementioned sophomore is now the afterthought and the first line carries the ring of a thesis: “I’m so self-conscious.” It feels prophetic now, to watch that tension between the hunger for success and the pitfalls of a hollow materialism — it pops out in a nervous laugh, a self-effacing grin, a stutter. Watch as he returns the next year, now the newly crowned prince with the Ralph Lauren polo and Louis Vuitton backpack to perform “Gold Digger,” an equally brilliant single about protecting your hard-earned fortune from scheming women. Or, the year after that, where he is now accompanied by an entire designer luggage set. He struts on like a model. Looks out with poised apathy. But as he performs, this time the emotional “Bittersweet Poetry,” any façade, any new distance to the audience is still stripped away as he embodies the explosive end to a relationship, a fight whose root, revealed in a searing final monologue, is infidelity on the touring life. Viewed back to back, the performance is practically a Hamartic tragedy in three acts. Watch how the more he bares his insecurity, the life of celebrity he clearly loves yet fears, the more he is greeted by applause.

The Def Poetry performances are the same story that travels through the desolate and manipulative “Paranoid,” where love is rendered glistening but transactional at the Heartbreak Hotel, or in “I Am a God,” where brag rap mythopoesis is juxtaposed with the trapped, blood-curdling screams of a panic attack. When modern classic “Power,” another track beloved for its hype and swagger, ends with contemplations of suicide, it doesn’t even register as out of place. As West grows more famous, gains more power, the stakes grow larger, the gaps between desire and reality, past and present, widen toward unbridgeable. It is the revelation that some contradictions are too great to overcome. That Yin and Yang can coexist, in fact must coexist, but not by only feeding one side of the beast. This is why Coates’ call to Kanye to simply “come home” to his roots is, at the end of the day, as reactionary as a Blue-Checkmark on twitter believing a Biden presidency will bring politics “back to normal.” You can’t simply unlive what’s been lived, force the “good” to defeat the “bad.” We can see this most clearly in West’s return to Christianity: what was once expressed so potently in songs like “Jesus Walks” is reduced now to just the same filtering through the ego. On 2019’s “Jesus Is King,” the religion of camels and eyes of needles is warped into complaints about the tax rate on the one percent.

At the end of the day, my continued interest in Kanye does bely a certain privilege: I do not, convoluted literary metaphors aside, relate to Kanye on a particularly racial wavelength. When he says what he says or does what he does I can vehemently disagree, but I don’t experience it as an affront to my identity. But if you’re like me and still holding on to your mid-2000s playlists, we can finally face the question a decade and a half in the making: why, after everything, do we still care about Kanye? Why should we? To me, the answer might begin at a second microgenre born of the Kanye media nexus: the Runaway Live Performance Video. If Kanye is the most discussed artist of the decade, then “Runaway” is perhaps his most discussed song, a critical standout even in a career defined by critical acclaim, and (at least according to some nerds who spend their time on this sort of thing) the sixth best single of the last decade. There are many reasons why “Runaway” is looked at as a magnum opus. It is highly ambitious: it clocks in at over nine minutes, and features a string orchestra and vocoder outro. The beat is pristine, maximalist but restrained; a dusty piano line sits like crystal above sinister, booming drums and bass. The hook is an instant earworm. At the end of the day, what elevates it to so many is the feeling of authenticity, the hollow rebuke you can hear in a claim like, “Let’s have a toast for the assholes.” Kanye excavates his personal failings with an unflinching honesty never reached before or since.

So much that there is to say about “Runaway” has already been said. But what is so compelling to me is not necessarily just the content, but the way that the song, as a piece of art, is transformed in its interaction with the image of itself, the song as a cultural icon. Because “Runaway” is only about the deeply personal as much as it is about the machinations of celebrity and fame. It’s the kind of thing you notice when you begin to watch every live recording of “Runaway” ever uploaded to YouTube in a row, the small particulars that change or carry through. The video affords what the live concert doesn’t — not just the ability to experience a performance, but to study it. The Internet makes voyeurs of us all.

The most viral example of the Live Runaway genre, 2013’s “Kanye West f[******] around and playing Runaway on the MPC,” only captures the first minute of the song, but it is entirely evident that the real magic is distilled right there in those first precious seconds. Kanye steps up to the MPC Controller and plays one single note, a sampled high E. And the crowd goes so absolutely wild that it almost feels like parody, but the moment is so instant, and clarifying, and undeniable in the way that the Internet can feel at its best, undeniable in the way that no think piece will ever be. It is an answer to our question: we care because Kanye, at least at some time, was just that good.

There are finer details to note, too: consider the song’s vocal sample, taken from a 1981 live performance by Rick James. While James commands the audience, “Look at you,” asking them to examine their own beauty, in performance Kanye pushes the sample to its limit, spamming it, jabbing it wild so it lands somewhere between the finesse of a DJ Scratch and a YouTube Poop and it is clear that it now reflects not the audience but the man on stage; a celebrity that only exists in our collective looking. Or the MPC itself: since its original use at the song’s debut, Kanye almost exclusively utilizes it on tour for this song alone, a ritual as much as a tool. It stands as both an altar and a piece of prop comedy, a wink to the audience that the haunted instruments never existed except as a ghost in the machine — that the orchestra is not material but conjured by the body electric, that any authenticity is not merely a performance, but in fact only created in the moment of its own performance. But what strikes me the most is still the play at the beginning. How the moment of every concert’s most vulnerable self-loathing is preceded by the acknowledgement of its power over the crowd. Sometimes Kanye is gleeful, stoking the audience further, and other times he stands still, patiently waiting. I wish I could study his face in those moments, but — in the way that life is often poetry — in most closeups he is wearing a mask of diamonds, reflecting nothing but the lights of the stage and the pasty forearms holding up iPhones around him. In that moment, does he feel hope? That if this rehearsal of penance, performed over and over again like prayer can be so loved, that it must mean something? Or does he wonder instead whether there is any separating Yin and Yang at all, whether to reveal one’s demons, to ask an audience to run away will ever be met with anything but more sold out concerts, more Calabasas mansions, more applause. This is the magic of “Runaway”: as West asks one love to leave, the other love, the audience, is only that much more enchanted to stay. It is a microcosm as the whole, the revelation of the central conflict that manifests in so many different ways: between the man and his mirror image, the celebrity, the performance, the idea, a conflict certainly exacerbated by his circumstances but that lives in all of pop culture as a whole.

This is, at its core, the fundamental truth behind mass culture, and especially the pop star: it is fake. Phony. An illusion, a sausage made of lights and engineers and PR reps and ad agencies and makeup artists, supply chains of ghost-producers, ghostwriters for ghostwriters. This is not some Le-Wrong-Generation-Type Cynicism; it’s common knowledge. So when we consume mass culture, choose to worship our icon, Stan our Faves, we take up a bargain, that we won’t just be given reality in return, but something better, something hyperreal. Such perfect craft that we can forget the sausage entirely, get lost in the hypnosis of media. We relate to singers on a personal level; we share in the emotions of Taylor Swift, not the 50-year-old Swedish man whose words are in her mouth.

Here is another uncomfortable truth: while Kanye’s life has spiraled out particularly rough, he is by no means alone. We know it is difficult to live with fame. Statistics for this kind of thing are hard outside of marriage and divorce (where unsurprisingly the outlook is not great), but the fingerprints of this knowledge are all over culture, to the point where more or less every story we tell about celebrity and entertainment somehow invokes the depravity or loneliness or emptiness experienced by its creators, to the point where it’s hardly uncommon for celebrities from old, established names to rappers as young as your humble columnist to die from drug overdose, and in fact the younger we decide to celebritize someone the less we bother even acting surprised when their life goes to shit, and it’s the kind of thing that just feels so incredibly sick if you think about it for too long. And deep down we know that there’s probably no correlation between proclivity for divorce and how well you can act or sing, but rather that celebrity, and its ineffable power, are to blame — a celebrity generated by the devotion, the obsessive participation of people like you and me. At his best, on tracks like “Runaway,” Kanye excavates this friction, the untenable compromise always present in our society of materialism and mass spectacle, our simultaneous desire for truth and fiction, the touchably real and the construction underneath it. Something more than honesty, a realness that can only be found in acknowledging what is unreal. His music reminds us of what is always there under the surface, and ever so often transcends it entirely, in the promise of a different, more radical authenticity than anything else in pop.

Contact Wilder Seitz at wseitz ‘at’ stanford.edu.