Werner Herzog is no stranger to madness. The legendary German director has engaged in his fair share of incredibly strenuous, but ultimately unnecessary, feats. As a young man, he walked on foot from Munich to Paris, believing that his physical act would save his ailing mentor. He moved a steamboat over a mountain to make a movie about a man moving a boat over the mountain. He cooked and ate his own shoe on camera. Even more passive events that Herzog has been involved with, like walking off a wound after being shot mid-interview, add to his aura as the master of the extreme.

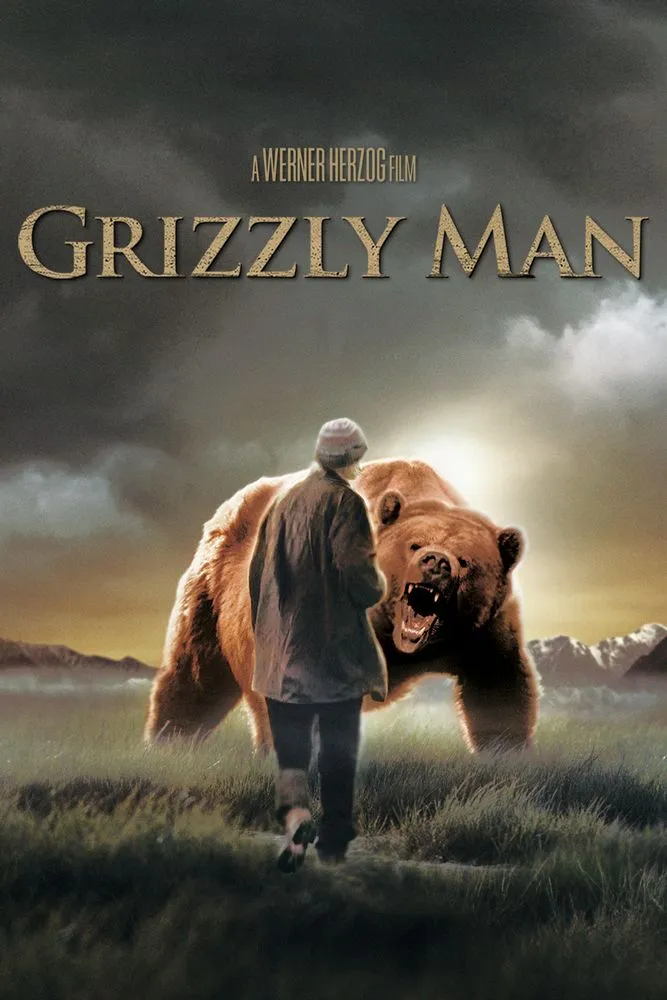

It makes perfect sense that he is drawn to the story of Timothy Treadwell, the titular “Grizzly Man” that Herzog directs his camera eye to in his 2005 documentary. The story of Treadwell has since been popularized; for 13 summers, he made trips to Katmai National Park in Alaska, where he would live in alarmingly close proximity with the resident grizzly bears (very often in direct conflict with official park rules), making observations and “protecting” the animals from poachers. It’s easy to see where this story goes: In the 13th summer, Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, are attacked and eaten by one of the animals he was there to keep safe.

As the eventual outcome of Treadwell’s endeavor is revealed in the beginning, the film becomes an exploration of man’s role in nature, masculinity and ego. During his last few summers in the wilderness, Treadwell carried a video camera with him, capturing footage of both the bears and himself, stylizing himself as a Steve Irwin-like character giving updates on his grizzly neighbors. In a few memorable moments, Treadwell also uses the camera to try to build himself up, yelling in anger at the park officials who don’t agree with his methods or talking about his trouble “with the ladies.” Mining these more intimate moments for full effect, Herzog combines Treadwell’s tapes with interviews from the people who knew him or his story: ecologists, friends, parents and the coroner who had to dig through his remains (giving a hilariously dramatic performance). Herzog engages with these often eccentric characters in close quarters, lingering on their faces after they stop talking, as if trying to get them to consider further what they have said. Their opinions on Treadwell range from viewing him with admiration to considering him completely delusional -— as more than one interviewee notes, “He wanted to become a bear.” Herzog steers away from these extremes; a man of his experience simply believes everyone is capable of their own eccentricities. He seems preoccupied with what Treadwell could have found in these hulking mammals that made him feel like a substantial enough being to befriend them. While he does intone his own judgement by the film’s end, he doesn’t do so in an indicting manner, treating Treadwell more as a fellow traveller than a defendant.

Herzog maintains a relatively muted visual aesthetic, both in his interviews and in his trips to the field. Partially, this seems to be to keep in step with Treadwell’s own, decidedly low-fi footage; Herzog praises Treadwell’s ability as a filmmaker to capture images, some beautiful and some not, that speak loudly (a fox’s paws appearing through the canvas of a tent as it walks atop of it, the rawness of the bears’ interactions with one another, Treadwell himself taking cover inside a tent as a storm beats it down). It almost seems as if Herzog’s respect for Treadwell comes from his ability to circumvent the German’s own idea of “ecstatic truth,” that the real resonant essence generated in cinema is not created from a simple portrayal of things as they are, but through a process of partial fabrication. And Treadwell does falsify, especially in creating himself: Throughout the film, he is shown taking multiple takes of himself talking to the camera, trying on slightly different personas in order to achieve his desired effect. But the other images he captures are undeniably raw; maybe if he had lived to put the movie together, he would have created more of an “ecstatic” experience though his editing and narrative choices.

Fifteen years later, “Grizzly Man” still comes across as a gripping and tragic portrait. The most questionable aspect might be Herzog’s own narration and presence in the film (most notably when he listens to the recorded sounds of Treadwell’s death, captured on videocassette and left to Jewel Palovak, Treadwell’s former girlfriend and employee), especially for viewers unfamiliar with the man. But for those previously acquainted, they will probably consider Herzog has earned this degree of self-reflection in the narrative, and he uses the film to ponder what Treadwell could possibly have been after in the wild. His droned conclusion, that “I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility and murder,” is enough of an induction into his philosophy.

Also, his willingness to externalize his attempts to connect with Treadwell’s story encourages audience members to do so, as well. Treadwell’s initial forays into the wilderness came as part of his inability to “fit in” and find success in society; in the brush, he finds a freedom undefined by artificial human rules (other than the park mandates which he regularly disobeys) in which he can freely exist. As a biologist, I’ve spent some extended periods in the field, away from some of the structures and infrastructures that make life what it is. It’s freeing… and enticing. Life is simpler and unfettered of the conflicts that we find ourselves mired in in “the real world.” Treadwell, a failed actor, a heterosexual man who felt he couldn’t connect with women, a person who considered himself not to be given the greatness he deserved, had plenty of reasons to escape initially. However, the freedom that he found is what may have kept him coming back.

While Treadwell’s story may have ended in “Grizzly Man,” Herzog has not slowed down. The 78-year-old had a new fiction film released in 2019 (“Family Romance, LLC”) and a new documentary (“Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds”) released at TIFF this year. In the past decade, he’s been on screen in properties including “Jack Reacher,” “The Mandalorian” and “Parks and Recreation” (remember the creepy guy in that old house April and Andy wanted to buy?). He’s dabbled with 3D, made a crazy Nic Cage movie and, yes, had his own Masterclass. He remains (sometimes hilariously) esoteric and philosophical, and his voice has become a recognizable and definitive feature. But, as established of a master and as recognizable as Herzog is, it remains exciting and emotional to engage with his work.

Contact Daniel Shaykevich at shaykeda ‘at’ stanford.edu.