“You’re my mother,” Daughter says in K-Ming Chang’s “Bestiary,” “and you’re supposed to prepare me for any future.”

“But who,” Mother replies, “can prepare you for the past?”

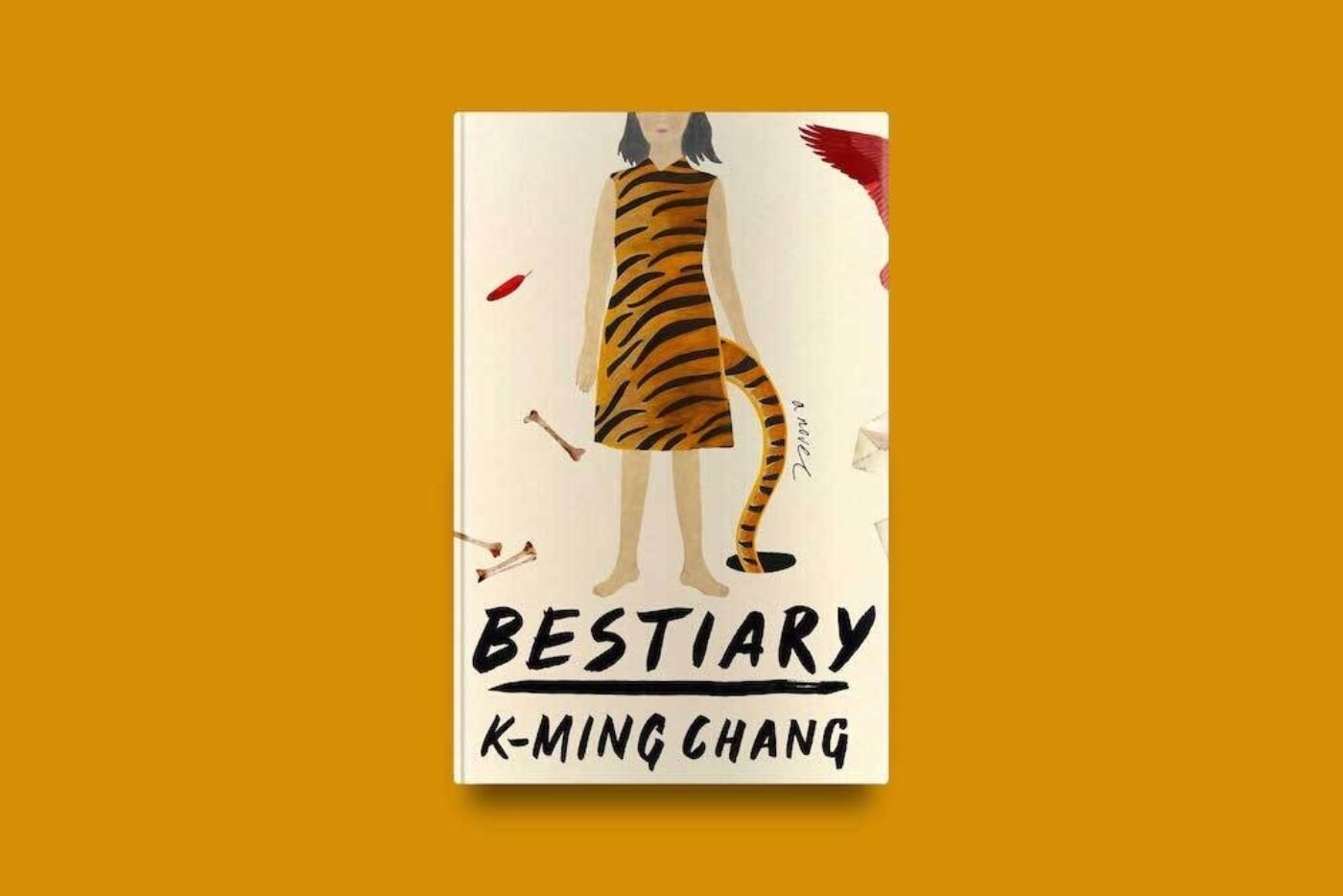

K-Ming Chang’s debut novel “Bestiary” was released in September 2020. Told primarily from the perspective of Daughter, with additional input from Mother and Grandmother, the novel utilizes Chinese and Taiwanese mythology to explore one Taiwanese American family’s history of migrations, romances and secrets. At the start of the novel, Mother tells Daughter the story of Hu Gu Po, a tiger spirit who bites the toes off of children. Afterwards, Daughter finds a tiger tail growing from her back. Daughter then meets and falls in love with a girl at school named Ben. Together, they translate letters extracted from a hole in the ground, referred to as the 口.These letters, written by Grandmother and addressed to her daughters, reveal the family’s past — part myth, part history — in Taiwan.

It’s difficult, in retrospect, to pinpoint an absolute beginning and ending to “Bestiary.” The stories within the novel are cyclic: The past holds immediate relevance to the present. A father tells his children the myth of a moon made of rabbit bones; decades later, he gives birth to a rabbit. Daughter’s unearthing of her family history is as much the conclusion as it is the origin of the novel.

Although Daughter is the primary narrator, the novel occasionally switches to Mother’s perspective, usually in conversation with Daughter. At times, I found myself unable to distinguish between their voices; Chang’s prose retains the same surrealistic beauty and strange intimacy regardless of the narrator. I have the sense that Mother and Daughter share the same body, the same voice, the same stories: Story and body are, after all, inextricably bound together. Once, Mother told Daughter that a body, after it died, “became a story, and death was just another translation of it.” When the family goes to the hospital after Daughter’s aunt suffers a stroke, Daughter recalls: “When the doctor asked if we had a history of heart disease, my mother said no, we have no history, just stories, just a long record of surviving our countries.” Perhaps, more than anything else, what’s passed down from generation to generation of Daughter’s transnational family are the stories that tie them not only to one another, but also to the places they call home.

“Bestiary” reads like a dream: somewhere between history and story, somewhere between myth and memory. Chang’s language is too gritty to be fantasy, too magical to be real. Daughter’s ancestry is rich with stories; there are countless avenues through which to understand her origins. In one story, Daughter is born with gnats in her stomach that she must drink insecticide to rid; in another, she is born with a gourd-shaped head that her mother must mold into a sphere; in yet another, she is conceived “in [her mother’s] mouth, born between her teeth and tongue.” Even now, I’m not sure what parts of the novel are myth and what parts are not; however, trying to answer this question would be ignoring what makes this novel so enthralling: The family’s lineage in “Bestiary” anchors itself to spirits, animal births and bodies of water. Everything in this novel is real in the same way that everything in this novel is myth.

I first encountered Chang’s work several years ago through her poetry — I’m still devastated by her exploration of war, motherhood and language in her poem “Yilan” in “The Shade Journal,” which was included in the 2019 Pushcart Prize Anthology. From “Bestiary,” it’s easy to see Chang’s poetic beginnings: Every single sentence is rich with startling and inventive imagery. For instance, Chang writes, from Daughter’s perspective: “Every night, a puddle flared around me like a skirt, wetting the whole mattress and waking my mother, who dreamed a typhoon had torn me from her tit.” Each new image compounds with the previous, creating a patchwork of myths and memories.

Chang’s language is rife with contradictions, yet these contradictions ultimately enrich the voices in this novel. People, in her prose, are both beautiful and hideous. Love, in her prose, is both intimate and disturbing. When Ben and Daughter kiss, Daughter “[thinks] of tonguing all her teeth and keeping them alive in my cheek, seeds of her mouth I could spit out and plant later.” Chang melds the distance between magic and reality until there is no distance at all. While reading her grandmother’s final letter, Daughter notes, “She’d written that my mother was conceived with the river, and Agong didn’t look like a river to me, except when he wet himself, his piss souring the seat.” Gore and love are both reduced and made complex: After Hu Go Po claims the body of a woman, “every child in the village [wakes] with a toe subtracted from each foot,” yet Mother’s vaccine scar is described more whimsically, as “lake-shaped, waiting to be entered.”

Although language in “Bestiary” forms the building blocks of the myths central to the novel, it fails the novel’s characters in so many ways. I keep thinking about Grandmother’s reaction to the Nationalists’ seizure of her land: “Watakushi, she said again and again. It is mine. It is mine.” Even Grandmother’s act of claiming her land is filtered through a language forced on her through imperialism. Even Grandmother’s letters, translated from Tayal by Daughter and Ben, are composed of fragmented phrases. Throughout the novel, pieces of language — the names of generals, dialogue in guoyu — are left blank, a hole in the narrative.

While reading “Bestiary,” I wanted constantly to go back to the beginning and start over again, convinced that I’d glossed over an extra image, an extra line that further complicates the overlapping narratives that Chang crafts. In this way, “Bestiary” is full of loose threads, but in the best way possible: It’s as if the novel was cut from the fabric of a greater conglomeration of mythologies that are impossible to fully capture in just a novel.

In one of the final scenes of the novel, Daughter writes a letter to Grandmother. She observes “a lace of holes where [she had] written the words and then erased them, inventing a language from friction.” Chang’s prose is, more than anything else, consumed with friction; she writes in a way that is conscious of the failings of language, yet wields it with such control. Chang writes a world in which nothing is pure and everything is beautiful, leaving me, in the end, haunted by these myths and the voices that tell them.

Contact Lily Zhou at lilyzhou ‘at’ stanford.edu.