Meet Emily: She is waifish, beautiful and wholly American. We know she is American because she adores her job at a marketing firm, runs 5.3 miles in 41 minutes and has an all-American boyfriend who drinks beer and likes the Cubs. He goes to sports bars and wears button-down shirts.

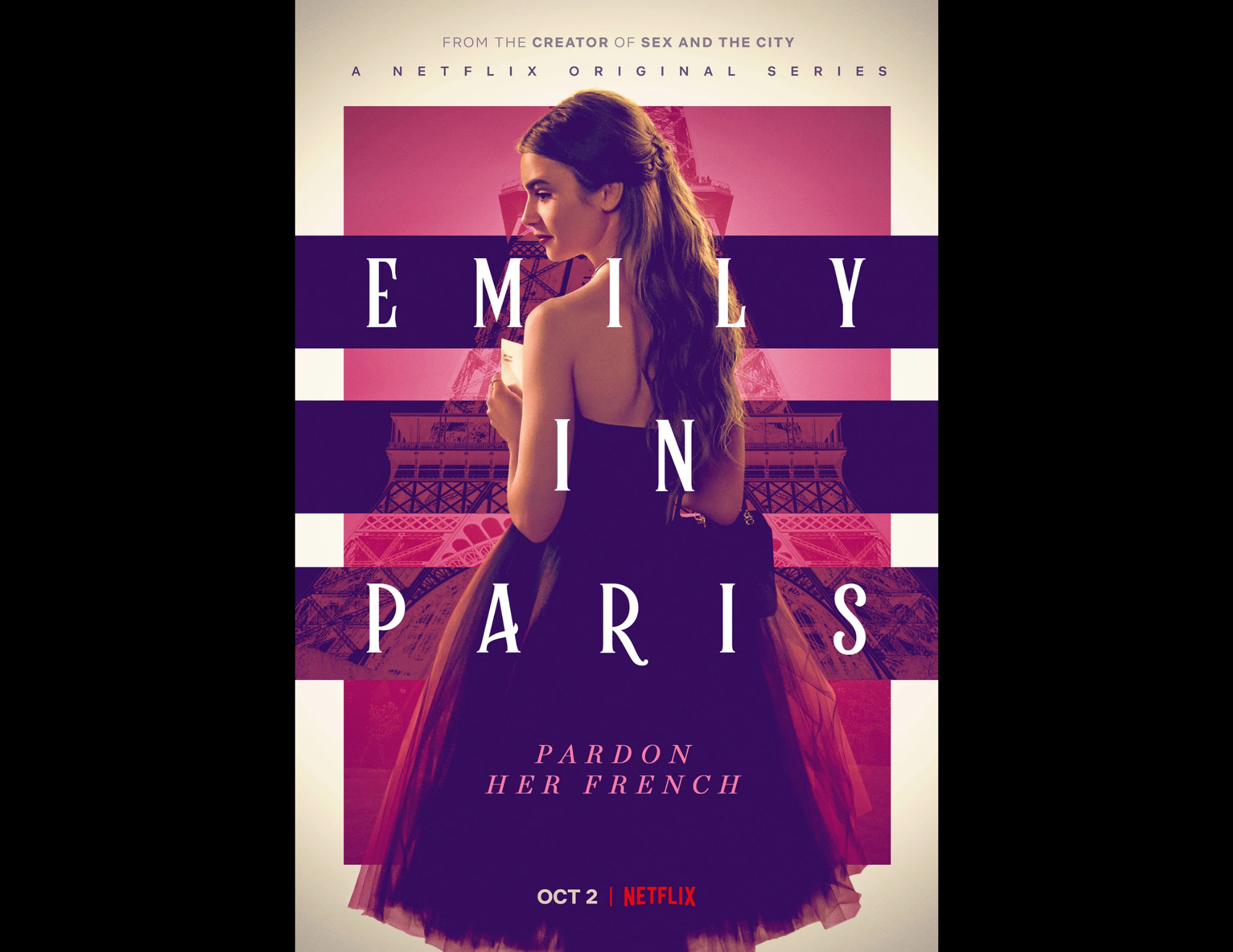

In the pilot of its 2020 comedy-drama “Emily in Paris,” Netflix has given us a technicolor propaganda short for American exceptionalism. Starring Lily Collins as Emily Cooper, the show follows a Chicago marketing executive who relocates to Paris to help a luxury brand with its “social media engagement.” (An exciting paradox: Emily herself has only 48 followers on Instagram.)

Made by “Sex and the City” creator Darren Star, “Emily in Paris” retains his signature mimosas-and-kitten-heels aesthetic while introducing a preoccupation with an American “love of work” and how the French are simply too “laissez-faire” to handle it.

Star’s Paris is the Panera Bread French onion soup of France depictions: see-through, bland and a little bit cheesy. Every Frenchman is attractive and sexually interested in Emily and every woman is middle-aged, judgy and rude. There is an entire scene dedicated strictly to the eating of a pain au chocolat — just a few berets away from being outright cartoonish. Emily flits through Paris like a guest at the Epcot World Showcase — speaking English to every cashier, getting offended if misunderstood — and eventually summarizes her impressions to her all-American sports boyfriend by saying, “The entire city looks like Ratatouille.” (The caricatures do not end here. In one scene, Emily’s bosses are discussing what kind of people they would be without pleasure. Her boss’s response? “German.”)

This is where the central tension of the pilot is revealed: Emily does not know any French. Her new coworkers are aghast. When she uses a voice app to translate herself from English to French, one coworker who wears whimsical white glasses physically runs away. Soon enough, the whole office is calling her “la plouc” — “the hick.” With blatant rudeness, they talk ill of her to her face and refuse to grab lunch with her.

Yet, Emily is saved by her signature American can-do attitude. When presenting her social media ideas to the team, her coworkers question her and her qualifications. Why do they need the perspective of this American girl who doesn’t know French?

“The French are masters of social media,” says one coworker.

“True,” replies Emily. “But Americans invented it, which is why I hope to be a valuable member of your team.”

This is single-handedly one of the best justifications for a job candidacy I’ve ever heard. It’s like saying you should inherit Frito-Lay because an American national invented the potato chip. Despite no qualifications or expertise, the show expects us to root for Emily as she operates with an American entitlement that deems her too unbothered to truly learn the language, to accept criticism or to listen to any advice at all. After all, she is doe-eyed and excited, and that should be enough. She’s there to “fake it ‘til you make it” more than anything.

The French, meanwhile, are portrayed as lazy and unmotivated. At Emily’s office, everyone starts working at 10:30 a.m. The coworkers smoke cigarettes and talk shop and go to long lunches — all to be contrasted with Emily’s spreadsheets-and-iced-coffee persona.

This contrasting portrayal of French and American work habits becomes my central qualm with Star’s “Emily in Paris.” While the French are depicted as sophisticated and pleasure-driven, the show virtue signals that a “work to live” instead of “live to work” mentality is morally wrong. Emily, meanwhile, is quick to claim that she enjoys work, that working hard and doing a good job make her happy.

This tension is best encapsulated in an exchange Emily has with her coworker Luc. Luc is the zany Frenchman of the show, which we know because he has wispy Einstein hair, rides an electric scooter and vapes casually. As the ethical heartbeat of the office, Luc approaches Emily in an outdoor cafe to apologize for how rude the other employees have been.

“[We are afraid of] your ideas,” Luc explains. “They are more new. Maybe they are better … Maybe we feel we have to work harder, make more money.”

The undercurrent of this exchange works out to this: American Emily has better ideas, the French are too lazy to work hard and innovate and without an unqualified American twentysomething the brand is doomed for failure. The rhetoric here reinforces the notion that the American should live to work, should enjoy their work and inspire others to love their work too. Can’t Luc stop vaping for one second to get this?

By playing into central interests of capitalism — to convince the laborer to value their worth by production and to be emotionally invested in their production — “Emily in Paris” creates an ethic in which to find joy and fulfillment in labor is deemed the moral be-all and end-all. In an interview with podcaster Jay Shetty, Collins admits this, “[Emily] has all these attributes that admittedly get a bad rap — like loving to work.” Yet, the issue is not Emily’s individual love of work — that might be fine within a more multidimensional character. The problem is that it’s her only personality trait.

The character’s identity is largely derived from what the show calls a “can-do attitude.” But, in reality, this “can-do attitude” is an insistence that her social media acumen is inherently better than that of the French, that she should talk about her marketing deals for pharmaceutical products at dinner parties and that the pleasure-driven whims and fancies of the French are ethically inferior.

“Emily in Paris” makes a capitalist argument a moral argument. By deeming one culture better than another, one economic system more virtuous than another, Star’s Netflix show makes caricatures of the French and parrots the idea that America is best.

Contact Valerie Trapp at trappv22 ‘at’ stanford.edu.