“I think I can remember / being dead,” Louise Glück writes in her 2006 collection of poetry “Averno.” “Many times, in winter, / I approached Zeus. Tell me, I would ask him, / how can I endure the earth?”

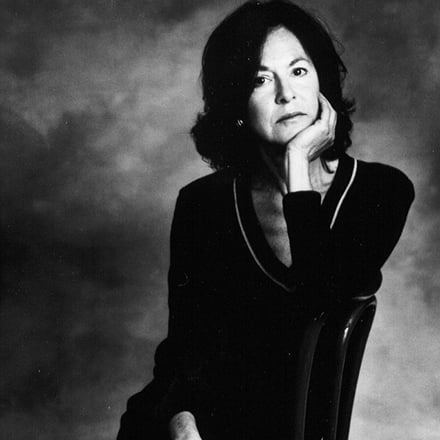

Recently awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature, Glück writes in a way that makes me very conscious of the relationship between the body and the natural world. When writing about nature, it’s all too easy to think about it as a reflection of human emotion: I’m in awe of nature, and so I write to preserve that beauty in writing; or I’m sad or angry, and I want to write a world where everything is about my sadness or anger. Instead, in “Averno,” there’s the sense that what is felt in the land is also felt in the body, and vice-versa. The speaker in Glück’s poems is ever-present, yet also seems to exist passively; the speaker’s function is to watch, to listen and to remember. “My body has grown cold like the stripped fields,” she writes in her poem “October,” and this image plays out in two directions of causality. The speaker’s body is cold, thus the stripped fields. Alternatively: the stripped fields, thus the coldness of the body.

For so much imagery about nature, Glück’s poems are, more often than not, hinged upon the witnessing of that nature and the memory of that witnessing. For instance, in the poem “October,” she writes: “Come to me, said the world. / This is not to say / it spoke in exact sentences / but that I perceived beauty in this manner.” Every modicum of beauty in Glück’s poems is filtered through the speaker’s mind: The world is beautiful because the speaker believes it to be so, and the speaker’s perception of that beauty is, to me, beautiful. Similarly, in her poem “Landscape,” Glück writes: “I can verify / that when the sun sets in winter it is / incomparably beautiful … I think this means / there was no night. / The night was in my head.” More than the physical beauty of the natural world itself, I’m enraptured by how cherished the memory of this beauty is to the speaker. Perhaps these recollections of beauty are more potent than the original beauty was by itself.

Glück’s earth is cyclic in nature: No grief is too great, and no action is ever too permanent. She concludes her titular poem “Averno” with the lines, “[The farmer] understood that the earth / didn’t know how to mourn, that it would change instead. / And then go on existing without him.” The poems in “Averno” cycle through seasons, through day and night, through barrenness and life. In the poem “October,” Glück writes, “summer after summer has ended,” and questions, “is it winter again, is it cold again.” Nature, in these poems, is never a fixed state, but rather always in the process of becoming something else. A burned field, for instance, will eventually be erased from the earth’s consciousness. After all, as Glück writes in the poem “Averno,” “Nature, it turns out, isn’t like us; / it doesn’t have a warehouse of memory.” The burned field exists only in the memories of people, until the people, too, are erased from the earth.

Glück’s poems carry tenderness for the people within them. In her retelling of the myth of Persephone in the poem “Persephone the Wanderer,” Glück interjects into the narrative, “You are allowed to like / no one, you know. The characters / are not people. / They are aspects of a dilemma or conflict.” This assertion of the characters’ inhumanity ultimately raises the question: How would we feel about these characters if they existed outside of words on a page or a conflict in a story? After all, these characters and their myths are intertwined with nature. The title of this collection, “Averno,” is introduced as not just “a small crater lake,” but also “the entrance to the underworld.” Similarly, Glück’s reimagining of Persephone’s abduction by Hades serves, in some ways, as an explanation for the natural world. She writes in “Persephone the Wanderer” that “[Persephone] doesn’t know / what winter is, only that / she is what causes it.”

Glück’s poetry, at first glance, seems detached from the human condition — yet after finishing the collection, I’m struck by how human these poems are. Perhaps it’s the way that nature permeates everything that we know about the people in these poems. In “October,” she writes, “What others found in art, / I found in nature. What others found / in human love, I found in nature. / Very simple.” Certainly, Glück’s poems are about nature, but through nature, we reach art and human love.

In the final lines of the collection, the speaker asks Zeus “how [to] endure the earth.” Zeus replies, “in a short time you will be here again. / And in the time between / you will forget everything / those fields of ice will be / the meadows of Elysium.” Glück’s poems are full of love and grief, yet there’s so little finality to these emotions. What we once knew to be true about the earth will be true once again; until then, we’re left only with these brief moments of beauty.

Contact Lily Zhou at lilyzhou ‘at’ stanford.edu.