“The Sea” by John Banville — Recommended by Lily Nilipour

In October, the year is waning. Time plays tricks on us in October: the daylight lessening, the nights “endless.” It is the month of hauntings too — of extended twilights and sudden changes in the wind. It marks the beginning of the period in which we recount the year that has passed us by. It is the time to remember.

John Banville’s “The Sea” takes place in October. Max, an older man whose wife has just passed away from cancer, decides to rent a room in a seaside house — the site of one particularly formative summer from his childhood. Through the novel, Max recounts the memories of that summer as he tries to gather himself back to life after recent tragedy. But rather than being a novel of reckoning with one’s past, “The Sea” only dredges up the ghosts of old selves, and does so in a manner so strong that these ghosts begin to take on new lives, overshadowing the reality of the now. The past fully possesses the present; Max disintegrates, losing any remaining sense of self; time cackles; the waves move in and out, unceasingly.

“Perfume: The Story of a Murderer” by Patrick Süskind — Recommended by Ellie Wong

Meet Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, an orphan growing up in Paris during the 1700s. Equipped with an extraordinary sense of smell, he can identify practically every smell in the city — until he comes across a girl just going into puberty. He’s enamored and wants no one else to smell it, so he strangles her.

This literary fantasy novel follows Grenouille as he learns the art of perfume making while also committing a succession of murders to preserve the scents of young girls. Süskind’s descriptions of their deaths are more than grotesque, but the ability of smell to persuade humanity is an even more horrifying concept.

Grenouille’s complete mastery of scents allows him to create odors of power, desire and innocence. In doing so, he can change the minds of hundreds of people without them knowing how or why he has affected them. “Perfume: The Story of a Murderer” is one of those books that will leave you unsettled for days after, wondering if (or when) technology will reach that level of power.

“The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon” by Stephen King — Recommended by Valerie Trapp

I read this book when I was eight. I am too young to read it now. My grandparents have very few books at their house, and so I read this book. It’s about a little girl who takes a bathroom break on a hike with her family and gets lost in the woods. All she has is a Walkman that she uses to listen to a baseball game in which her favorite player — Tom Gordon — is playing. I don’t know what’s scarier about this book: the amount of baseball references I don’t understand, or the fact that she gets super dehydrated and loses her mind. At the end, she comes face-to-face with an actual, non-hallucinatory bear, which is also not fun. This book made me too scared to pee during hikes for four years.

“Blood is Another Word for Hunger” by Rivers Solomon — Recommended by Emma Wang

In “Blood is Another Word for Hunger,” Rivers Solomon explores the supernatural manifestations of motherhood, redemption and what it takes to be truly free. The story starts with the murder of a slave-owning family by their slave girl, Sully, an act that is powerful enough to disturb the balance between the etherworld and our own. From this disturbance comes Ziza, a teenage spirit from the etherworld who is literally reborn through Sully’s body.

The word “hunger” implies necessity, prompting us to reconsider the murder as a physical manifestation of Sully’s search for peace in addition to being an act of vengeance. However, even after her owners are gone, Sully’s insatiable hunger seems to only increase with the number of etherworld spirits that she births. In the last moments of the story, as Sully is being soothed by Ziza, she wonders, “How many moments like this would it take for her raucous, angry soul to be soothed? How many songs? Were there enough in the world?”

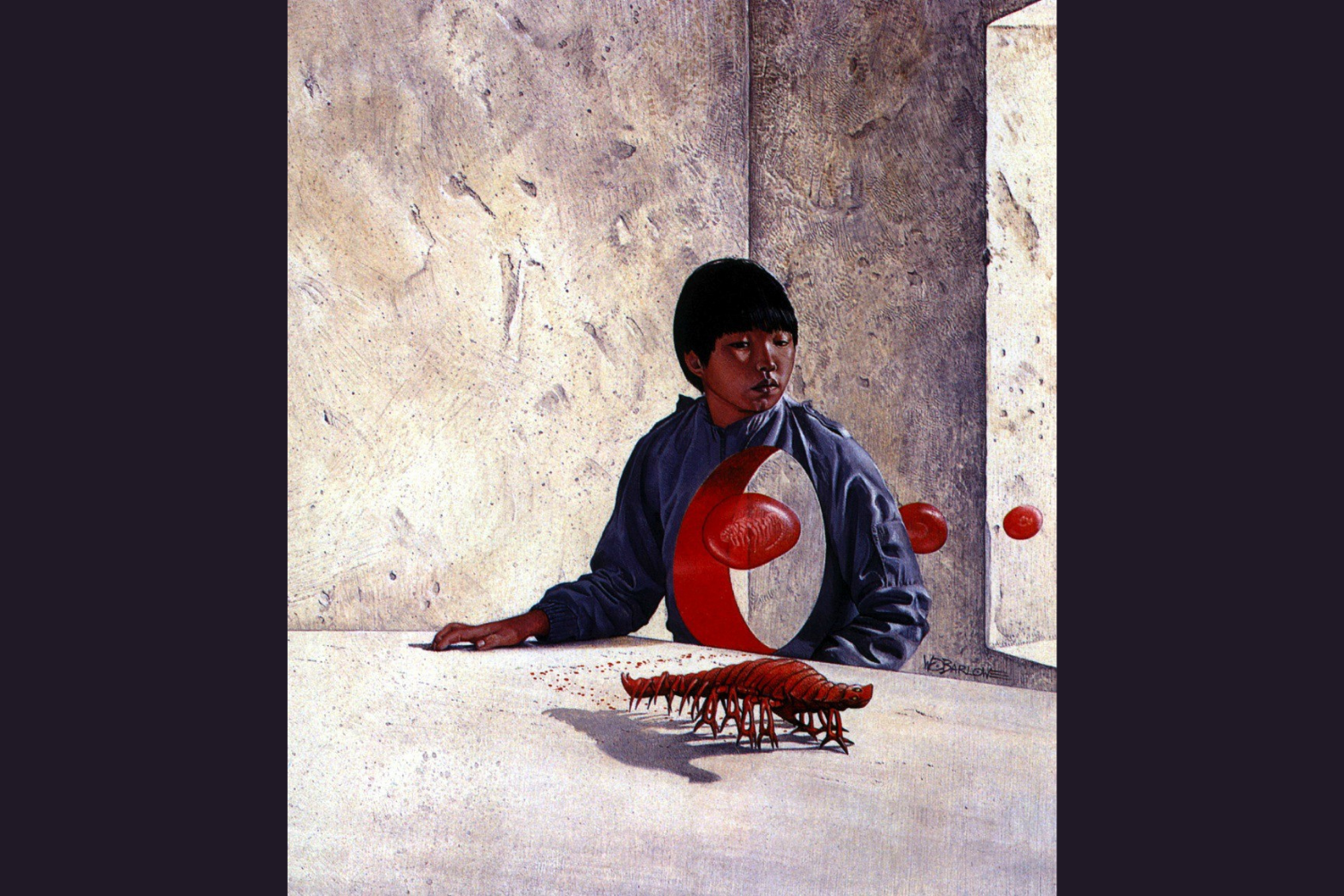

“Bloodchild” by Octavia Butler – Recommended by Shana Hadi

Drawing on the human instinctive revulsion to crawling centipedes and wriggling grubs, Butler deftly creates another planet where humans and the many-legged Tlic uneasily coexist, exploring the politics of sex and social oppression through this chilling short story. The human colonizers, heavily outnumbered, “voluntarily” live in Preserves in exchange for one child per family who will incubate the Tlic’s offspring in their body. The protagonist Gan, a human male groomed from birth to host his family friend T’Gatoi’s eggs, accidentally witnesses an incubation gone horribly wrong: “I saw red worms crawling over redder human flesh.”

As much as Butler expressively depicts the body horror of worms emerging from human skin, her seamless interweaving of description, worldbuilding and theme emphasizes the horror inherent in losing control. Wracked with fear and helplessness, Gan reluctantly assists in a surgical intervention while questioning the dynamics of his and T’Gatoi’s supposedly loving relationship, which is unavoidably characterized by the way most Tlics covet humans for their flesh, not their sentience. Caught between impossible choices lest he and his human colony risk complete annihilation, Gan must decide whether to sacrifice his autonomy, his morality, his sister or his own life.

“Bog Girl” by Karen Russell — Recommended by Cindy Xin

In Karen Russell’s short story “Bog Girl,” 15-year-old Cillian Eddowis finds the preserved 2000-year-old body of a teenage girl in a bog while turf-cutting. He immediately falls in love with her, despite their age gap and her lifeless state. What is surprising, however, is not that he can love someone who is basically dead — after all, she is beautiful, quiet and can be whoever he decides she is — but how little it seems to matter. In an absurd yet strangely inevitable twist, Bog Girl’s being dead does not stop the pair from going through almost all the archetypal features of first love — obsession, jealousy and parental disapproval — except for heartbreak and disillusionment, which do not arrive until Cillian discovers that Bog Girl is not as dead or blank as he would have hoped. Humorous yet insightful, Russell’s story illuminates the pitfalls of idealization and the blindness of young love. Contemplating how one could love the dead or unresponsive, “The Bog Girl” is a penetrating commentary on the manic pixie dream girl trope and the lure of objectification.

“The Semplica Girl Diaries” by George Saunders — Recommended by Carly Taylor

If you’re not ready to commit to a full novel this Halloween season, curl up by the fire with this short story and experience the concentrated horrors, both real and speculative, of late-stage capitalism. “The Semplica Girl Diaries” is written in the choppy, frenetic style of stories relayed over text, but rather than the flattening out emotion, Saunders’s narrator seizes the desperation at the heart of middle-class life with his disjointed syntax.

The reveal of this story is everything, so I’ll avoid telling you what Semplica Girls are, but I will tell you why it’s so terrifying. It illustrates how capitalism manipulates us into thinking that we can become one of the rich, all while keeping us one disaster away from destitution. It depicts a family caught in a materialist hellscape, where the divide between what they are made to want and what they are given to live with can never be bridged — and still, they will plunge themselves into ruin trying. This is a story of how the stunted modern attention span allows us to easily accept the most morally bankrupt of realities, and how seamlessly we trade in our childhood dreams of grandeur for a life of mere survival.

Contact Reads Desk Editor Carly Taylor at carly505 ‘at’ stanford.edu.