For over a century, Stanford’s Bay Area rivalry with the University of California, Berkeley is an integral part of the Cardinal identity.

“‘Beat Kal’ has always been the most universal sign of friendship among the international Stanford community,” said Abe Oliver ‘22, a member of Stanford’s Axe Committee. “My parents yelled it when I got in, I said it on my first day and I’ll absolutely say it as I throw my cap.”

“Strangers have said it to me on the street when I wear a Stanford shirt, and it’s the only thing I have ever heard the campus rally behind,” Oliver added.

But this year, Stanford and Berkeley are entering an unorthodox 123rd Big Game. Although Stanford leads the all-time series 65-47-11, Cal defeated the Cardinal last year in Stanford Stadium and took back The Axe for the first time since 2010. Entering the game, both teams have a winless record of 0-2, a first for the historic rivalry.

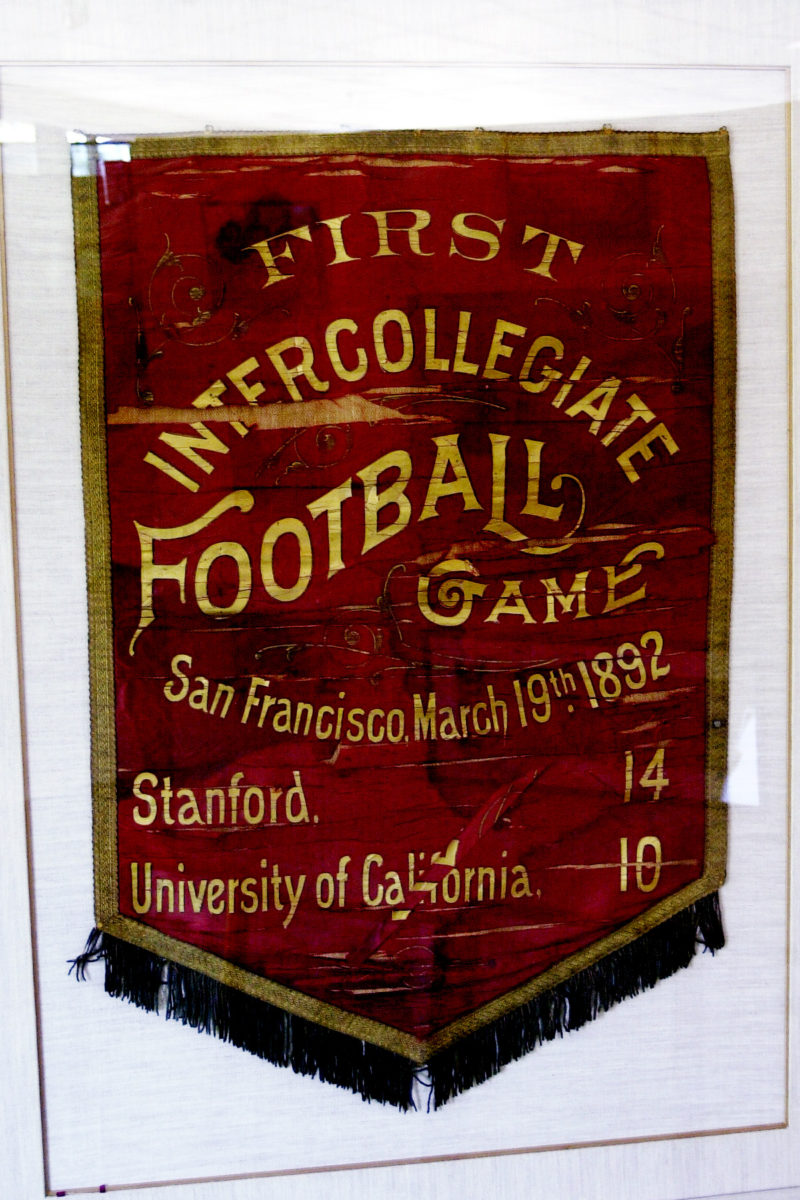

The rivalry is the 10th longest in college football and oldest on the west coast. The inaugural Big Game in 1892 was organized by Herbert Hoover ’95 and his friend at UC Berkeley, Herbert Lang. Hoover and Lang printed only 10,000 tickets for the first game and were forced to accommodate an overflow crowd of 20,000 at San Francisco’s Haight Street Grounds. The Big Game moved to the teams’ home stadiums in 1904, now alternating between Stanford in odd years and Berkeley in even years.

The Axe is an integral part of the rivalry’s history. Before there was a physical Axe, there was the Axe Yell — introduced by Will Irwin (class of 1899) in 1896 as a parody of Aristophanes’ The Frogs, a relic of an era when students were expected to know Ancient Greek.

“Will Irwin simply plagiarized a yell they did at Yale,” said Hal Mickelson ’71, a former student band announcer and Stanford Stadium announcer. Mickelson attributed the popularity of the yell to parodying Yale’s Ancient Greek chant and its “catchy rhythm.” The Axe Yell quickly became a staple across Stanford sports and is still used at both Stanford and Berkeley.

Former Stanford yell leader William Erb (class of 1901) introduced a physical axe in 1899 at a pre-game rally, using it to decapitate a straw man dressed in blue and gold. The Axe was stolen by Cal students two years later and recaptured by a group of Stanford students, dubbed the “Immortal 21,” in 1930. The 21 students disguised themselves as photographers and executed a complicated scheme, involving blinding flashbulbs, smoke bombs, elaborate disguises and getaway cars to recover The Axe.

In 1933, the schools agreed to use The Axe as a trophy, given to the winning team. Despite the agreement, The Axe was stolen several times, most recently by Stanford students in 1973.

The rivalry also has seen tragic moments. In 1900, the Big Game became the site of the deadliest spectator disaster at an American sporting event. When the roof of San Francisco and Pacific Glass Works collapsed, onlookers watching the game on it fell through the ceiling, leading to 22 deaths and 78 injuries.

Perhaps the most famous moment from the rivalry is Berkeley’s last-second victory in 1982 with “The Play.” Stanford had taken a 20-19 lead, but with four seconds left to play, Cal scored a controversial game-winning touchdown (taking down a trombonist from the Stanford band in the process). The Stanford Daily sought revenge by publishing a fake version of the Daily Cal, claiming that Berkeley’s victory had been vacated.

In 1990, Stanford also took victory in a last-minute switch-up, scoring nine points in the final 12 seconds of the game to end the game with an improbable 27-25 win.

More recently, in 2018, the Big Game was postponed for the first time since John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The game was delayed two weeks because of poor air quality due to the Camp Fire in Paradise, Calif., about 200 miles from Stanford’s campus.

While the Big Game is always a must-win for both teams, Cal’s victory in 2019 — ending Stanford’s historic nine-year run, the longest for either school — makes 2020 an especially competitive year

Even with high stakes for this, the 123rd Big Game, school spirit has been less visible this year, with most traditional Big Game week events moving online or cancelled altogether. While several traditional aspects of the game will be missing from California Memorial Stadium — including marching bands, the halftime show, Oski and the Stanford Tree — The Axe will still be displayed and presented to the winning team at the end of the game.

“In the old normal when almost all undergraduates lived on campus, the Big Game was ubiquitous and pervasive,” Mickelson said. “And you couldn’t ignore the fact that the big rivalry with California was coming up.”

Mickelson reflected on all the traditions, from the Ram’s Heads production of Gaieties to all the events hosted by the Axe Committee, that “were a fixture of the Stanford experience.”

“It’s painful that the [COVID-19] lockdown is taking a lot of these traditions away from students,” Mickelson said.

Axe Committee member Alex Bradfield ’21 said the rivalry “brought me way closer to my friends in Axe Comm through Big Game Countdown.”

“Camping out in the birdcage for the week is such a fun way to deepen friendships and also get to meet a ton of the Stanford community that comes together to celebrate Stanford spirit,” Bradfield continued. “It’s hard to replicate hanging out virtually, but I love seeing Axe Comm members and Stanford staff share what makes Big Game special with videos that they’ve sent in to be posted to our Instagram account.”

“This year, it’s unfortunate that so much is different and we can’t do a typical countdown,” Axe Committee member Carlino Cuono ’22 M.S. ’23 wrote. “However, we’re trying to make the best of it with a virtual countdown of videos (@axecomm), and that has been going surprisingly well!”

There are a few upsides to organizing during this time, according to Cuono.

“I think people appreciate being able to connect over Big Game even now,” Cuono wrote. “And I think it has been easier for various campus celebrities to get involved virtually.”

For frosh, connecting to the rivalry and Stanford school spirit has been especially difficult with the distance from Stanford’s campus.

“I think it’s much harder to connect with spirit online without the social aspect of sporting events like the student section,” Mario Nicolas ’24 said. “I watched the opening night game in my apartment with takeout, which is an interesting experience, and I expect the Big Game to feel similar.”

“It’s much harder to connect with school spirit online, and the Big Game is a microcosm of what the quarter has been like,” he added. “The academic and sporting experiences are isolating without the sense of community that comes with people cheering and crowding around each other.”

“Having one event and a rivalry to coalesce around actually helps build community,” Nicolas said. “I’m trying to be positive that with the Big Game all the group chats and clubs will have something to discuss and bond over.”

Mickelson expressed sympathies for students, especially frosh, struggling to connect to the Stanford community through a screen, saying, “I hope that we’ll be able to find unique ways to continue the tradition of the Big Game.”

Mickelson also drew a parallel between current circumstances and the origin of the Big Game and several of Stanford’s traditions.

“When Stanford opened in the 1890s, we were short on tradition, and needing to invent traditions is an interesting parallel to the COVID-19 emergency,” he said, “It’s almost a rerun of the 1890s when we were pioneers and alone, having to invent things ourselves.”

Contact Kaushikee Nayudu at knayudu ‘at’ stanford.edu.