Upon finishing Concepts of Modernity, the required philosophy class for all coterms and Ph.D.s in modern thought and literature, I accepted that I need to read more Foucault. After years of remaining skeptical and unmoved when hearing Foucault praised by countless TAs, Professor Hoyos and “The Subject and Power” broke me down — to understand modern thought, I must engage with Michel Foucault. I did not, however, expect to reunite with him quite so soon after the quarter’s end, upon opening Maria Cichosz’s debut novel “Cam & Beau.” Epigraphs from Foucault and fellow theorist Barthes preface sections of the novel as it jumps between the perspectives of its two protagonists, serving as guideposts to the novel’s themes: the weight of silence, the “limits of discourse,” the human struggle to share one’s heart and thoughts with another.

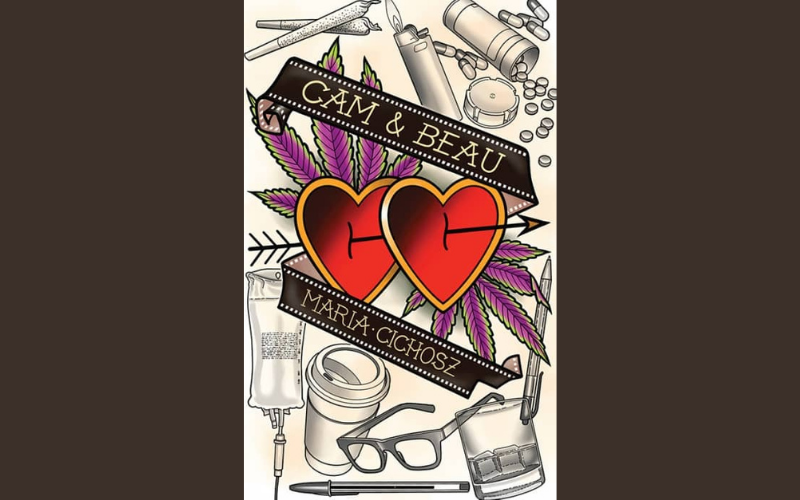

That this work is a romance — a troubled, stifled, complicated romance — is clear from the first two epigraphs: Barthes’ “A Lover’s Discourse” speaks of a “prophetic love,” while Foucault speaks of “which types of discourse is [sic] authorized.” This is a novel of queer romance and first young love, but it is also a novel of academia, of critical and all-consuming illness, of drugs and self-destruction.

As the novel alternates between the perspectives of Cam and Beau, we are let into the lives of two very different, and sometimes hopelessly entangled young men. Cam is a quiet, lanky, almost unbelievably brilliant Ph.D. student. Despite appearing through most of the novel as a caretaker or on drugs, Cam manages to achieve academic and professional feats that seem implausible even for someone not so burdened. The reader spends much time in Cam’s head, as he thinks about what he can and cannot say and agonizes over his possibly unrequited love. Beau is a photographer and barista, and he’s dealing with the crushing existential crisis of his life-threatening illness without a family to help him through it. He has no one other than his best friend and roommate, Cam.

Throughout the novel, these two circle each other; getting close and pulling back; unspoken words, feelings, fears and needs almost crushing them as they deal with the fragility of life — a challenge that rarely confronts young people. It is in this aspect that the book shines. Cichosz describes with gripping, raw accuracy the emotions of illness, care-taking and the all-consuming love that will drive a person to sacrifice their own well-being entirely for another’s.

Having experienced the physical and psychological pains of illness, as well as the emotional toll it exacts on those who love one most, I was deeply moved by Cichosz’s descriptions of these experiences. She plunges the reader into the hospital room, onto the bathroom floor, into the darkened bedroom, with remarkable accuracy and impact. Her understanding and portrayal of the antagonism of light and cold to the ill, how they press into one’s skull, bite into one’s core, are masterful. The heightened sensitivity and pain that comes from illness is described with such clarity that I want to force these passages upon my doctors when they ask how I am feeling. The experiences of those who live with but outside the illness are also vividly described. The reader is with them and their anxieties and guilts in the waiting room, during the doctor’s examination, hovering next to the hospital bed. This role, I’m sometimes convinced, is as hard or harder than the ill person’s. To love someone and watch them suffer beyond belief marks a human as much as the critical illness itself.

The novel’s romance plot is similarly deeply felt and visceral. The experience of loving someone more than life itself, and sometimes being unsure how they feel in return, is drawn onto the page with excruciating detail and verisimilitude. The related fear of opening up to the new while risking what one has is less explored, but this might be viewed by Cichosz as more self-explanatory. Though this plot can seem overly drawn out, taking hundreds of pages to climax before the shocking late twist complicates it even more, it is ultimately worth the wait.

I was less taken by this work as a novel of academia and drugs. Perhaps being too close to the world of theory and criticism made the scattered snippets of Barthes and Foucault, intended as keys to the characters’ inner dilemmas, seem a bit simplistic and obvious. That said, I cannot deny that academic scholarship is often tied to the questions that plague us personally — perhaps that’s why we do it. Whether a reader unfamiliar with literary and philosophical theory would be drawn into the story or instead mystified by these passages I cannot say.

The novel’s academic sections struck me as at once realistic and fantastical; the gruff old professor was highly believable, while the academic superstardom of a character who is usually drunk or high or both was less so. Could a Ph.D. student spend the vast majority of his time taking care of a critically ill or chemically altered roommate, a student who because of the two aforementioned activities consistently misses all the classes he is taking and teaching, not only succeed in his program but come out of it with one of the most impressive academic jobs I’ve ever heard of for a new graduate? Maybe? But it felt forced and a bit magical, a distraction from the rest of the novel’s realism. Though the answer is supposed to be that Cam is so brilliant he succeeds despite these obligations and coping mechanisms, as someone whose mother was my full time caregiver when I was in the depths of illness, spending my days and nights vomiting as Beau does, Cam’s monumental academic success felt too neat, too easy. Being a caretaker is an excruciating, all-consuming job, and to see the first literary depiction I have found of it end with that responsibility taking no professional toll was surprising.

Regarding Cam’s drug use, it is clearly a coping mechanism, a way to escape the crushing existential terror of his friend’s condition, but apart from it making his academic success seem even more unlikely, it was simply flat. To read once about the feelings of chemical intoxication is interesting, to continue reading about it for several hundred pages grew wearisome.

I was also dismayed that the only female main character was, if not a manic pixie dream girl, the academic version of that fantasy. Introduced as a potential love interest, she is never given much motivation, interiority or substance. She is unlikeable, though, arguably, the other main characters often are as well, but more disappointingly, she is flat, her motivations never made clear; her agency consists of literally following the men around. This is more disappointing because of its contrast with so many other of the novel’s descriptions that are layered and textured. The sights, smells and feel of the hospital, the lecture hall, Cam and Beau’s apartment and the emotions they invoke, are wonderfully detailed.

Though the suspense of wanting to see how major plot lines would play out propelled me through the novel, it is undeniably dense, with enough content to make at least two, if not three separate novels. While I appreciated the density and complexity — real life is rarely singular — I cannot help but wonder whether the price paid was a flattening of supporting characters and the sense that some major plot developments lacked foundations. However, overall, this is an impressive debut novel that realistically captures many aspects of life that need to be examined.

Illness, death, mortality, the mental crises that come from living with them every day are a vital part of the human experience. And yet, they are mostly absent from literature. We do not like to look at the ill, and often forget the caretaker even exists, until the day we become one or the other. This novel is important because it forces the reader to look at these things. Though the novel is about so many things, it is the raw and honest portrayal of grueling pain, bodily collapse and the psychic burden of watching those things attack the person you love most that makes the novel a vital contribution to the literary world.

Contact Jen Ehrlich at jene91 ‘at’ stanford.edu.