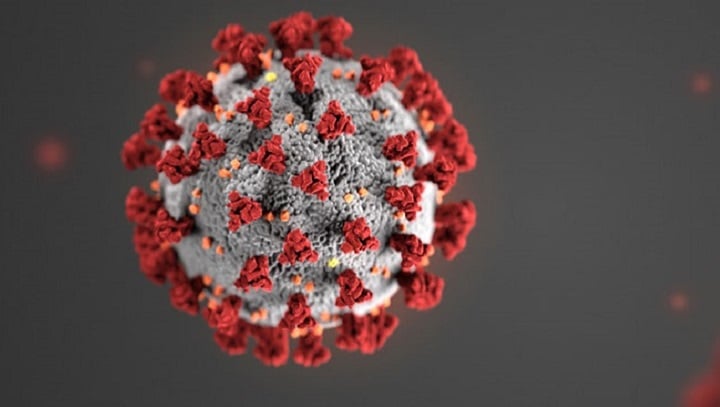

A Stanford-led research study showed that the spread of the COVID-19 occurs most frequently at “superspreader” sites such as restaurants, fitness centers and hotels. The study was recently published in Nature and supports the importance of reducing the capacity of large public spaces.

Computer science associate professor Jure Leskovec and his team used anonymized cellphone data to model the movements of 98 million people from various metropolitan areas across the U.S. They assessed three parameters: the fraction of infected people at the beginning of the study (early March), how likely the virus is to spread from one person to another at points of interest and the transmission rates for individual neighborhoods. By comparing their projected infections to real data, they were able to verify the model’s reliability and use it to forecast the number of future cases that would result from different public health policies and levels of mobility.

According to Leskovec, the model provides strong evidence that reducing the capacity of businesses greatly deterred the transmission of the virus when it first began to spread. “If we did not socially distance or reduce our mobility back in March, 30% of an entire population would be infected in a single month,” he said in an interview with The Daily. “This would have spread like fire.”

The findings also provide policymakers with insight regarding the feasibility of reopening plans. According to the study, businesses can find a “sweet spot” by reducing the capacity of high-density areas without shutting down completely.

“Reopening the economy is not an all-or-nothing type of strategy, but you can really fine-tune based on the maximum occupancy,” Leskovec said. “We show that there are very interesting non-linear effects to reopening.”

The model also indicated that the disproportionately high rate of infection among people of color and those from low-income neighborhoods is largely due to increased exposure to “superspreader” sites.

Melissa Bondy, chair of the department of epidemiology and public health, told The Daily that “part of it is that they’re in more service-related jobs.”

“They’re out in public more and might live in areas that are more congested,” she said. “A lot of them are our frontline workers, and if they get exposed to someone in their family who tests positive, they don’t have the access to go somewhere else and distance themselves.”

With this new information, Leskovec said policymakers could potentially change their approach to developing reopening strategies in low-income neighborhoods. “Now, since we are modeling disparities between different neighborhoods, it’s possible to use different strategies in terms of protective equipment, education, working at home and food delivery,” he said.

Currently, Leskovec’s team is working on making the model more robust by feeding it new data about COVID-19 infections and mask-wearing. As cases surge across the country, these results may be especially significant in determining whether reopening is safe.

While the study tracked the mobility of millions of people in major cities, Bondy believes that the study’s general results can be applied to something smaller in scale, such as Stanford’s campus. Due to Stanford’s relatively small size, contact tracing on campus isn’t nearly as difficult as it is in large cities. “With it being so small, people tend to know whether they’ve come in contact with someone who’s been exposed,” Bondy said.

University spokesperson E.J. Miranda told The Daily in an email that the decision to allow frosh and sophomores to live on campus in the winter was based on “on the public health situation on campus; the prevalence of cases in Santa Clara County and our surrounding region; the state and local health rules that apply to Stanford; and our ability to provide on-campus opportunities while protecting public health.” He declined to state whether the University was concerned about potential “superspreader” sites, such as dining areas, on campus.

According to an official statement from Senior Associate Vice Provost Shirley Everett, “Stanford Dining management team and staff have been hard at work putting in place new processes and procedures to provide a safe and secure dining hall environment for students and for the staff working there.” When entering dining halls, students must wash their hands, have their temperatures checked, wear facial coverings and maintain a six-foot physical separation from those around them. Stanford also limits the amount of time students spend in these locations by only providing pre-packed, takeout meals.

Santa Clara County’s public health officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Contact Katie Li at katie_li ‘at’ outlook.com.