Before quarantine, our homes, our dorm rooms, our bedrooms were our refuge — the spaces where we could take a break from the hustle and bustle of the world and be truly alone. But when we’ve been cooped up in these spaces since March 2020, only venturing out for the essentials, home — whether it’s your childhood home you’ve been thrust back into, a dorm room on an empty campus without a roommate or even a new place in a new city — has probably started to feel like a prison of sorts.

Now that most everything we do takes place on screens within our dwelling place — our school, our work, our social time, our leisure — it all blends together into a mass of time that’s difficult to differentiate. As the third and largest wave of COVID-19 infections overwhelms this country, even while vaccines are being gradually dispersed, we’re confronted with the reality that venturing out still will not be possible for many more months, if not longer. So how can we escape this feeling of being trapped in the places we reside, living the same day over and over again? Although Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book “The Poetics of Space” was not written with lockdown in mind, I think it provides us with some crucial tools for combating this sense of stasis.

By revisiting this philosophical classic in our confinement, we can learn to look with fresh eyes upon every aspect of the space we inhabit, no matter how small and seemingly dull, and find new intrigue within it. In addition, Bachelard can show us how to have a deeper experience of the spaces that literature and poetry create for us.

Even though “The Poetics of Space” was one of Bachelard’s final books, published when he was 73 years old, it takes daydreams and imagination as its subject and is filled with endearing exclamations of childlike wonder. His insights are mature and unique, and yet his tone is humble and always playful.

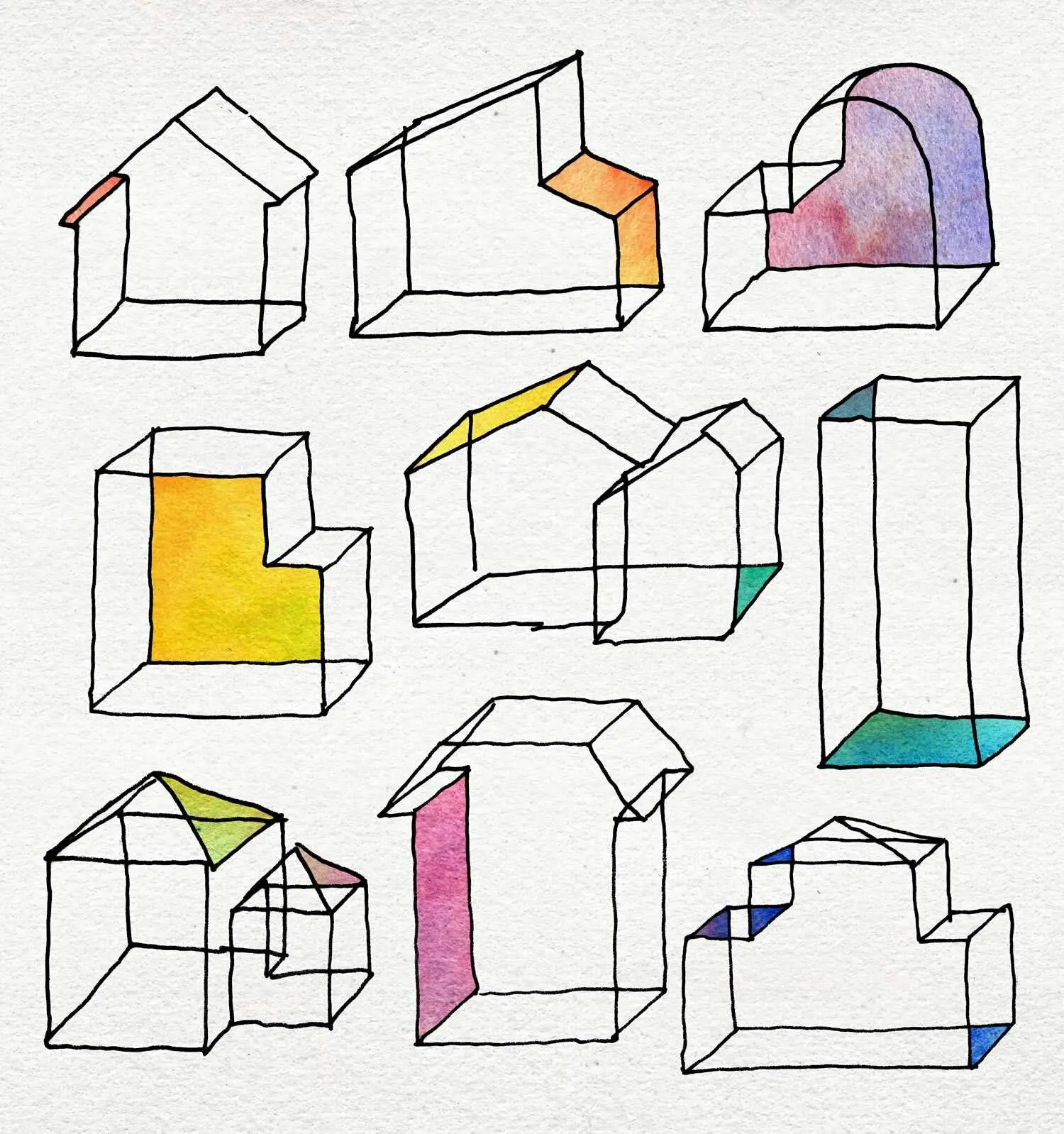

Wikipedia will tell you that “The Poetics of Space” is a book about architecture — to me, that’s like saying the Bible is a book about the desert. It’s no surprise that Bachelard begins this book with a couple chapters dedicated to the house as an archetypal dwelling place, but as the book goes on, he treats at chapter-length increasingly obscure subjects, like drawers, chests and wardrobes. The last several chapters move from these dwelling spaces and features within them into more abstract facets of our dreams of space, in chapters titled “Miniature,” “Intimate Immensity,” “The Dialectics of Outside and Inside” and “The Phenomenology of Roundness.” Any normal person faced with these titles would ask themselves, how could someone possibly have this much to say about corners, or nests or shells? This cracking open of the ordinary is achieved through Bachelard’s method of phenomenology.

If you’re humanities- or even social science-adjacent, you’ve probably heard the word “phenomenology” tossed around, and if you’ve ever asked someone to define it, you likely were not satisfied with their response. If you really want to learn what phenomenology is, I don’t suggest you read Husserl, who coined the term and defined its method. I suggest you read someone like Bachelard, who doesn’t bother defining the term and moves right along to putting it into practice. Phenomenology is better validated by the insights it produces than an explicit account of its method. Bachelard puts these insights on radiant display — I felt the need to underline every other sentence.

For Bachelard, “[I]mages are more demanding than ideas.” This is quite the opposite view of the analytical philosopher, who aims to find the idea that ultimately explains all the images we encounter. Because he values images over mere ideas, Bachleard takes various images conjured by poetry and literature as his primary phenomenological “documents” of study. No matter how bizarre and niche the subject of Bachelard’s analysis, he always furnishes us with ample poetic examples to illuminate his thinking. “[A] phenomenology of the imagination cannot be content with a reduction which would make the image a subordinate means of expression: it demands, on the contrary, that images be lived directly, that they be taken as sudden events in life. When the image is new, the world is new.”

No matter where we are, through our screens or through print, literature is readily available to us. If our poetic imagination is attuned like Bachelard’s, these can give us the necessary transport we all crave in our confinement. “[W]e still have books, and they give our daydreams countless dwelling-places.”

Lying just under the surface of Bachelard’s text is a powerful framework for individually resisting the most insidious aspects of our capitalist, productivity-obsessed culture. In reading Bachelard this year, I noticed several affinities between him and another incredible book I read in 2020: “How to do Nothing,” by Stanford’s own Jenny Odell, a visiting lecturer in Art Practice. “How to do Nothing” is, of course, not about literally doing nothing — it’s about doing nothing in the eyes of capitalism, which is actually doing a great deal. For example, in our society, even the practice of reading is framed as consumption done in one correct way — you move through the words on the page in sequential order, and if your mind wanders and you lose focus, you’re doing something wrong. You’ve failed to read correctly by moving into a daydream.

But Bachelard presents the opposite view — “To read poetry is essentially to daydream” — particularly in the case when a writer is trying to convey to someone the sense of intimacy contained in a space: “Paradoxically, in order to suggest the values of intimacy, we have to induce in the reader a state of suspended reading. For it is not until his eyes have left the page that recollections of my room can become a threshold of oneirism for him.”

Bachelard and Odell both make a case for reclaiming our right to “do nothing” and to daydream by illuminating the great value of letting our minds wander. It’s perhaps no surprise that they both explicitly praise a kind of work that a capitalist culture of innovation and progress has no respect for: maintenance work and routine caretaking. Bachelard has great respect for the housewife, whose attention and care remakes the space of the home anew each day: “The housewife awakens furniture that was asleep… A house that shines from the care it receives appears to have been rebuilt from the inside; it is as though it were new inside.”

I began reading this book myself when I tested positive for COVID-19 in late October and had to be isolated in my bedroom for 10 days. I was following a vague instinct that meditations on space would help me feel more at ease in my confinement, and I was not disappointed. Bachelard’s faith in poetry and his valorization of the child’s naive wonder make his book ever life-affirming and refreshing, even six decades later. There is no one I trust more than a philosopher who understands and perfectly articulates the pitfalls of philosophy itself, and a wise old man who has maintained the clear eyes of a child:

“Philosophy makes us ripen quickly, crystallizes us into a state of maturity. How, then, without de-philosophizing ourselves, may we hope to experience the shocks that being receives from new images, shocks that are always the phenomena of youthful being? When we are at an age to imagine, we cannot say why or how we imagine. Then, when we could say how we imagine, we cease to imagine. Therefore, we must dematurize ourselves.”

Contact Carly Taylor at carly505 ‘at’ stanford.edu.