Anyone who writes, makes art or has an appreciation for either field has their own individual dream of Paris. Since I study literary modernism, I dream of Paris in the 1920s — of Gertrude Stein’s infamous salons and Sylvia Beach’s lending library Shakespeare & Company, good coffee and cheap English-language books. Sometimes you do not even need to be very serious about your love of art to dream of Paris; you can also love the idea of art, and the idea of famous writers sitting in cafes and drinking wine, the idea of you sitting where James Joyce or Picasso might have sat. The idea of simply being there, at the center of creation and avant-gardism.

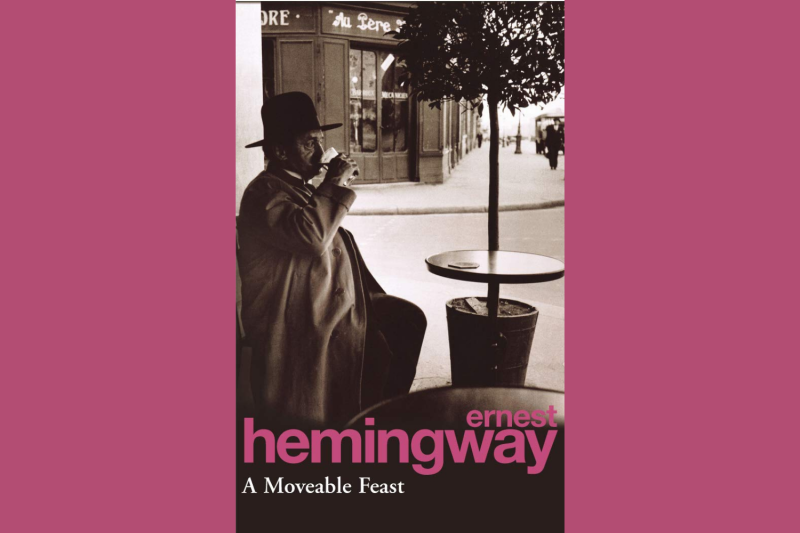

Recently, a good friend of mine sent me a copy of “A Moveable Feast,” Ernest Hemingway’s posthumously published memoir of Paris in the ’20s, “because I feel like we are artist friends,” she said. With the pandemic, both my friend and I are taking time off from Stanford, and so the past months have been spent reading and talking a lot about books. Now that we are stuck at home, the dreams of Paris seem to have become amplified. Thus the dream is not only for the city itself: It is now a dream to escape from the confines of quarantine, to be able to live cheaply and freely and only think about art.

Since this escapist fantasy is not currently possible, what I have left to do is to read and continue to dream. “A Moveable Feast” makes this easy; the memoir is a poignant and endearing sketch of 1920s Paris and the real-life characters that animated it.

Most of the events in “A Moveable Feast” occurred before Hemingway published his first novel, “The Sun Also Rises,” and so we see the author reflecting on himself and his experiences as a young, up-and-coming writer. In Paris with his first wife Hadley, Hemingway is surrounded by some of the foremost modernist artists of the day: Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ford Madox Ford, Wyndham Lewis, Stein, Joyce and more. During these interactions, Hemingway himself often disappears into the background of his narration, allowing the other person he is with to animate the story.

That is part of the appeal of “A Moveable Feast”: While reading, we feel like we are in the room with Hemingway and whoever else is with him, watching with an almost voyeuristic eye the capers of these literary celebrities. We feel as though we are being let in on secrets. We learn about the impetus for Gertrude Stein’s initial dislike of Ezra Pound (not because of his poetry, but “because he had sat down too quickly on a small, fragile and, doubtless, uncomfortable chair … and had either cracked or broken it”), about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s strange intolerance to alcohol and about how Hemingway thought Wyndham Lewis “the nastiest man” he had ever seen. The larger-than-life names we see on our bookshelves come to life at the tip of Hemingway’s pen. Their characters are rounded out; they feel almost real — as real as you can get with words.

Regardless of what we learn of these people, they become somewhat endearing to us, for through Hemingway’s retrospective eyes, the great qualities of his past friends are brightened and the less-great qualities forgiven. For this is what time does: polishes good memories into lustrous pearls and blunts sharp blades with nostalgia.

Besides the appeal of “A Moveable Feast” as a writer’s fantasy, the memoir also contains many of Hemingway’s pithy remarks on the act of writing. Hidden behind the eccentric anecdotes of our beloved modernists are glimpses into the formation of the modernist writer Hemingway himself. We see his determined work ethic and philosophies on truth, observation and omission. Because “A Moveable Feast” was published posthumously, there have been many edits to the original, unfinished manuscript. I read the restored edition, which includes prefatory material from some of Hemingway’s progeny and preserves rawer “Additional Paris Sketches” which Hemingway didn’t get the chance to fully complete or edit, but which offer an even fuller version of the Paris he wanted to capture.

But, from this whole text, what I found most enlightening was the final section titled “Fragments,” which is composed of “transcriptions of handwritten drafts of false starts for the introduction” of the book. Indeed, these are “false starts”; the short paragraphs sound like a glitchy computer program, spitting out some sentences that are completely different and some that are exactly the same. Hemingway clearly struggled with the age-old writer’s challenge: how to begin. Each “fragment” offers some new insight to the reader that the previous did not contain.

Yet as we read these pieces, we realize how much each one also omits from the previous. Hemingway believed that fiction should be “cut ruthlessly” — that the “lesson” a story teaches should always be omitted, only present in the gaps between the words on the page. The fragments remind us that even this text, with real people and real events, is constructed, and suggests that the paradise 1920s Paris seems to be may not have been that way at all. We might enjoy it for the brief escape it offers, but perhaps that is all it is.

One thing that is present in nearly every fragment, one thing that is never omitted: “This book is fiction.”

Contact Lily Nilipour at lilynil ‘at’ stanford.edu.