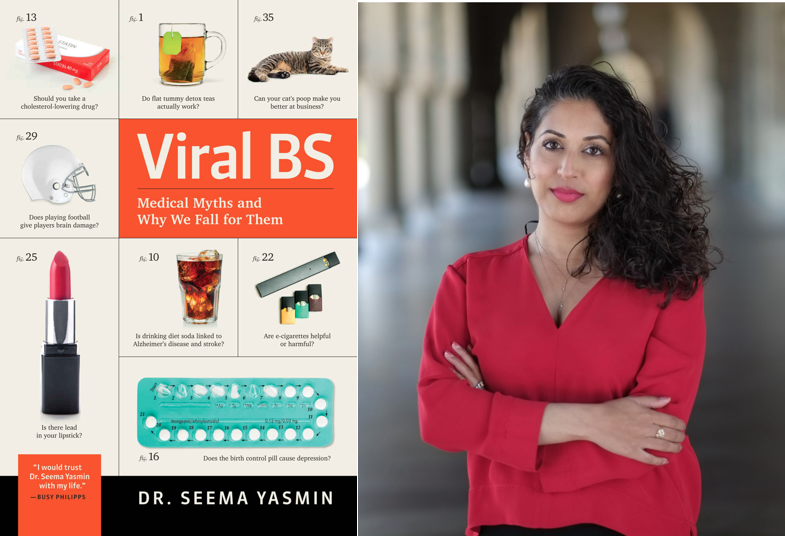

Our guest this time hardly needs any introduction. Director of the Stanford Health Communication Initiative, Dr. Seema Yasmin, is an Emmy-award winning journalist and medical doctor. She was previously a science correspondent at The Dallas Morning News and a medical analyst for CNN. She now teaches science journalism at Stanford University.

Dr. Yasmin joins us this time to talk about her latest book, “Viral BS: Medical Myths and Why We Fall For Them.” With topics like ‘Are you more likely to die from a medical mistake than from a car crash?’, ‘Is it dangerous to be pregnant in America?’, ‘Do vaccines cause autism?’ and ‘Why do immigrants in America live longer than American-born people?’ — we journey into the history of medical misinformation and disinformation.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for readability.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): In the introduction of your book, you describe yourself as a disease detective. Can you tell us what a disease detective is?

Dr. Seema Yasmin (SY): Disease detective is the colloquial name given to Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers, which is the job I first moved to America for ten years ago. EIS Officers are the U.S. government’s squad of doctors and scientists who are trained to respond to outbreaks of disease around the world. My job involved investigating outbreaks of flesh-eating bacteria, pertussis, botulism and other diseases.

TSD: Apart from being a disease detective, you are also an award-winning journalist, newspaper reporter, a public health doctor and a professor. How does wearing these hats shape the way you approach medical misinformation and conspiracies?

SY: My varied training and lived experiences help me to look at these issues from more than one perspective. In the introduction of “Viral BS”, I described myself as a teenaged conspiracy theorist, and that experience, along with my faith and upbringing make me see more than just the medical problem behind the spread of health and science misinformation and disinformation. For example, as I track the spread of pandemic-related false information, now I see that anti-science groups are not just peddling lies about the dangers of masks and vaccines; they are framing masks and vaccines as oppositional to the American way of life. Some of them say that wearing a mask means you are anti-American and anti-freedom. These are challenges that go beyond correcting false information to probing and countering deep-seated cultural and political beliefs about government and society. A multifaceted problem requires a multidisciplinary approach.

TSD: What do you think influences the way people interpret medical information?

SY: History, culture, faith, community, education, among other factors. The way we process and interpret data is complex and it’s why providing more information, simply correcting falsehoods and offering facts can be ineffective in shifting beliefs and changing behavior. And when it comes to medicine’s dirty history, we’re dealing with a legacy of unethical experimentation, exploitation and racism that fomented legitimate distrust in the establishment, at least among particular groups of people such as queer people, disabled people, immigrants, the incarcerated and people of color. That’s why it’s insufficient and unhelpful and ahistorical for doctors and scientists to say “trust us” without doing the work of acknowledging and atoning for our profession’s past.

TSD: Why do you think people are prone to believing things that are not true?

SY: Because seemingly unbelievable things that we would hope to be untrue have actually happened. And because governments and those we should be able to trust have broken that trust and failed to rebuild healthy relationships with the people they serve. That’s why saying “but this data comes from scientists or the government” might not sway people who have been hurt by those institutions, and it can make those communities more vulnerable to believing untruths by charlatans and anti-science organizations who do a better job of building connections and trust with those populations.

TSD: From your point of view, what are the most common factors propagating the spread of misinformation?

SY: Poor access to credible, well-sourced information makes people vulnerable to exposure and belief in false information. Crises themselves heighten public fear and anxiety which can be exploited by those spreading misinformation and disinformation, and can leave people susceptible to inexpertly assessing the information. It can be harder to apply logic and make rational decisions when you are scared for your life. That fear can be exploited.

TSD: What are some of the impacts of medical misinformation?

SY: It can cause harm and even death. People may hear about something that is said to prevent COVID-19 or be led to believe that they are not at risk. In the best case scenario, a false intervention might be something like a saltwater gargle which in itself won’t cause harm. But even then, it could lead people to falsely assess their risk of contracting COVID-19 and motivate them to not wear a mask, for example, in the belief that they are protected by the intervention.

TSD: Here is a paragraph from your introduction that I think captures the content of your book so well: “The true stories we bury sprout fake stories, like fungi blooming from dead tree trunks. There is sometimes an inkling of truth in a conspiracy theory, and these truths wrapped in history and suspicion can spread faster than microbes, infecting people with a deeper distrust of doctors and science.” Why is exposing misinformation and conspiracy important for you?

SY: I think about my family who care deeply about their health and their community’s health but who are exposed to a host of false information, including conspiracy theories about COVID-19 and other diseases. They are immigrants — some are not fluent in English, and they have reason to both distrust the government and the press (given the documented evidence that media representation of Muslims is often inaccurate and negative). I want to make sure that communities like mine who are already at heightened risk of some diseases are given the best available information, information that speaks directly to their concerns and needs, so that they can make informed decisions about their health.

We talk about health equity in terms of access to health care, but we don’t talk enough about information equity and people’s ability to access health and science information in ways that make sense to their circumstances and needs. My research, supported by the Emerson Collective, looks at the overlap of medical deserts and news deserts in the U.S. Medical deserts are regions where people lack good access to health care, and news deserts are regions where access to credible local news is lacking. We’re finally talking about access to broadband internet as a social determinant of health in epidemiology, and my research seeks to understand the impact of information inequity on our health and our community’s health.

TSD: Scientific knowledge changes over time. New results and observations can either strengthen the current position or replace it entirely. Knowing the changing nature of science, how should we be approaching scientific claims?

SY: I think it is really important to remember that science is not just a bunch of facts, science isn’t a textbook: science is a dynamic process that evolves over time. Science is very much a human endeavor — scientists are not robots. We bring all of our biases and cultural lenses, our upbringings and perspectives to the lab and to the way we design experiments and analyze data. So I think good science literacy isn’t just saying to people “believe science, science is right” — no! — we need to peel back the curtain on the scientific process, invite in the communities often excluded from that formal process of information-making and teach the skills to critically appraise the work of scientists.

TSD: Is science literacy the job of the expert? How would someone without a science background approach science literacy?

SY: I think it is the role of scientists to make that process transparent and the information accessible. I detest the chasm between the scientific establishment and marginalized people. Scientists should, in my opinion, work with the communities whose lives are impacted by the science they produce.

TSD: If inaccurate information could come from experts as well as government bodies, should we be worried? Is our fear justified?

SY: It is. Because we have a documented history of government and doctors and people of power exploiting the more vulnerable people in society. If you look at the speculum, and some routine gynecological surgeries, they were designed by racists, men who experimented on enslaved Black women, many of whom had not been anaesthetised. That’s our legacy. And that is just one example amongst many. That is why we need transparency and accountability, and why we cannot trust those in power to take care of the needs of the most vulnerable in the society. We need systems of accountability and processes that protect the most vulnerable.

TSD: What new publications are you working on?

SY: My next book, “If God is a Virus,” is my debut poetry collection and it will be published in April. Some of the poems are documentary poems based on my reporting on the Ebola epidemic from West Africa. Other poems interrogate the role of scientists and medical aid organizations in responding to epidemics, as well as poems about the journalistic process. I think working across genres offers different ways to access information and emotion, and offers the reader — I hope — a different way to examine a problem.

Contact Kristel Tjandra at ktjandra ‘at’ stanford.edu.