This article contains mentions of sexual assault and harassment that may be troubling to some readers.

Since her debut album in 1996, Fiona Apple has been flattened into archetypes by popular media for public consumption. She’s known as either the 18-year-old nymphet undressing herself for the camera on MTV or the Maya Angelou fan muttering “there’s no hope for women” during photoshoots or the reclusive auteur who takes years to release albums with 90-word titles.

But when I first listened to Apple’s music at age 16, I found undercurrents of something else: myself. Her music, at once angry and percussive and lyrical and lovestruck, seemed to decode my own emotions. After all, as other moody queer girls who read Rookie Magazine during lunch can attest, I felt alone in the muck of teenagerdom. Fiona Apple kept me company. I would begin to find community in college, but that, of course, was temporary.

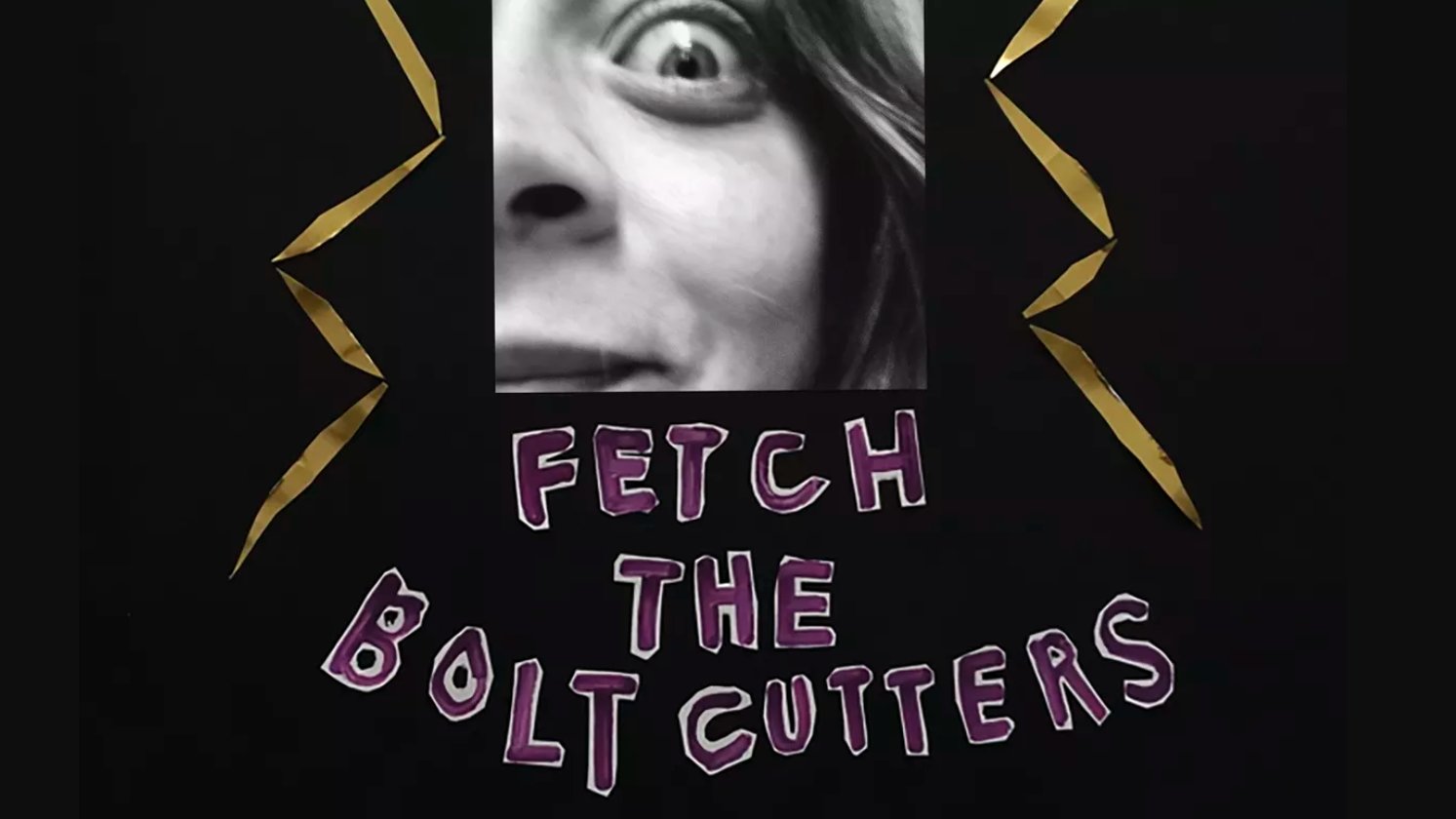

In April 2020, Apple released her fifth studio album to near-universal acclaim. “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” was the first album to receive a perfect score from Pitchfork in a decade and is the second-highest-rated album of all time on Metacritic. Its strangely prophetic production caught the attention of critics; despite being recorded over a five year period and being released at the very beginning of the United States’ struggle with COVID-19, it was produced entirely in Apple’s Los Angeles home.

I first listened to “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” only a month after I was sent home from my freshman year of college due to the pandemic. Confined to my childhood home by quarantine and faced with friendships wilting under the stress of the pandemic, I felt isolated. The album’s title track resonated: “Fetch the bolt cutters,” Apple sings, “I’ve been in here too long.” During the track’s production, Apple and her creative collaborator kept their dogs behind a shut door, where they remained silent for most of the song. In a perfect coincidence, the dogs only erupted into barking at the tail-end of the track. They, too, yearned for the freedom Apple demanded or, perhaps, the company of someone they loved beyond an impenetrable door.

In an interview with Vulture, Apple defined fetching the bolt cutters as “breaking out of whatever prison you’ve allowed yourself to live in.” For her, music has historically been a way to artistically conquer sexual oppression; Apple was raped when she was 12 and was thrust into the unyielding gaze of fame by 19. In “For Her,” Apple takes on the perspective of an anonymous friend to describe the friend’s assault.

“Good morning,” she half-screams, “You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.”

Though this pain is greater than my own, Apple’s expression of it in music spoke to a woundedness that I found all too familiar.

Sexual misconduct claims toward no fewer than five of my friends, all of whom I had known for years, came to light during the pandemic. These claims were largely unrelated, and my connection to all of them was a terrible coincidence. One case involved a friend from high school whom I previously recommended for club leadership positions; this friend used their new authority to solicit nudes from underclassmen. Another claim implicated one of my role models — an adult in their mid-20s whom I partnered with to lead an online affinity group for young adults; they were later ousted from the group for sexual behavior surrounding children. Others were accused of assault, verbal abuse and leveraging power to have sex with younger adults. I broke ties with each of these friends in response. On “Drumset,” Apple repeatedly cries, “Why did you take it all away?” I was not a direct victim of the misconduct, but I felt my trust taken away, stolen.

My friends’ wrongdoing haunted me. At first, I wondered how I could have been surrounded by so much harm and not have known it. Then, I sank into a depressive state alongside the realization that much of my adolescence was, in fact, mired in sexual harm and manipulation. “Time is elastic,” Apple sings on “I Want You to Love Me.” My brain could not help but dwell in my past in order to make sense of my present.

My ex-friends hurting children sparked flashbacks: to the time I was added to a group chat by high school upperclassmen when I was 14, where they told me how hot they found me and how they “need[ed] to stop jerking off to [me],” where they asked who my favorite porn stars were and told me they would visit me in a hotel room I stayed in alone during a quizbowl tournament. All this, before I began menstruating.

I was plagued by nightmares of my high school assistant coach, who was arrested for creating child pornography of his female students years prior. School administration did not inform me of his arrest, despite me being the young woman he interacted with the most during his time at the school, so I found out from a news article.

I met with the principal afterwards, and pleaded with him: Why hadn’t anyone told me? Why hadn’t anyone made sure I was okay? Why did I have to seek out a social worker myself? He said that wasn’t school policy. I went on with my day, later emailing my senior portrait to the detective on the case. No one told me the detective was asking students to email their photographs for comparison to the pornography. I found that out from the news, too.

I was, thankfully, not one of the impacted students, yet the memory lingered, which was perhaps the most frustrating part of it all. The times I had been forcibly kissed and groped and followed for blocks by strangers did not haunt me; for me, personal betrayal trumped the degree of violation I had suffered.

Why did you take it all away?

Lost friends and role models and authority figures melded into a cynicism towards loved ones I couldn’t shake; “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” guided me through this alienation.

This past year, I spent many walks through my neighborhood immersed in Apple’s music because it captured so much of what I was feeling. The anger in the title track: “I was just so furious, but I couldn’t show you.” The warning against too much anger in “Relay”: “But I know that if I hate you for hating me I will have entered the endless rage.” The loneliness in “Newspaper”: “I’m alone on the summit, trying not to let my light go out.”

Over the last few months, the nightmares have become less frequent, but the loneliness remains. Like everyone else, I’m waiting for the end of a historical era of isolation. More than anything, I want a future free of the disillusionment of my teenage years, free of disappointment in the people I love. Some pain I can’t bring myself to revisit hangs between the lines of this essay. Why did you take it all away? For now, I get the perfect album as solace. I wonder, in all this projecting of my own experiences onto the music of Fiona Apple, whether I’ve flattened her into a two-dimensional mirror, capturing only one side of a complex person just like the rest of the world. I hope she doesn’t mind the reflection she’s lent me over the years. In “On I Go,” the final track on Fetch the Bolt Cutters, Apple sings, “In the long run, if I get there in time, it’ll be alright.” On I go, indeed.