I entered Stanford University in the fall of 1966, majoring in Physics and looking forward to a career in the emerging computer industry. I had read how the Stanford Provost, Frederick Emmons Terman, Jr., had pioneered the concept of a “Community of Technical Scholars,” combining campus brainpower with local industry to create what later became known as Silicon Valley.

Unfortunately, the narrative failed to mention a third partner, the U.S. Department of Defense. Stanford’s Engineering School and the university’s wholly owned subsidiary, the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), were essential elements of the military industrial complex. At that time, it meant that Stanford research had gone to war in Southeast Asia.

By the time I arrived, the Stanford community was already leaning against the Vietnam War, but most people on campus did not recognize the university’s connection to it. So my friends and I launched a multi-year campaign to “Get Stanford out of Southeast Asia.” We conducted research, published pamphlets, held rallies and teach-ins and attended official meetings to which we were not invited.

As we gradually built majority support for our demands, we recognized that Stanford is not a democratic institution. It is a corporation with thousands of employees and more land than Mountain View, governed by a self-perpetuating Board of Trustees. So we resorted to direct action — sit-ins, building and street blockades and even window-breaking. We did not achieve all of our goals, but we did change Stanford for the better as we changed the aspirations and perspectives of ourselves and our cohort.

Lenny Siegel read SDS demands to “Get Stanford out of Southeast Asia” to the Stanford Board of Trustees at the Faculty Club, Jan. 14, 1969.

My activities, from crashing a Trustees’ meeting to throwing a police tear-gas canister into SRI, terminated my academic career, sent me briefly to jail and, ironically, disqualified me for the military draft. Of course, the Vietnam War and the anti-war movement profoundly affected the futures of most students in that era.

Stanford anti-war organizing, ranging from political campaigning to militant confrontations with police, spanned a decade in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but it reached a peak in the spring terms of 1969 and 1970.

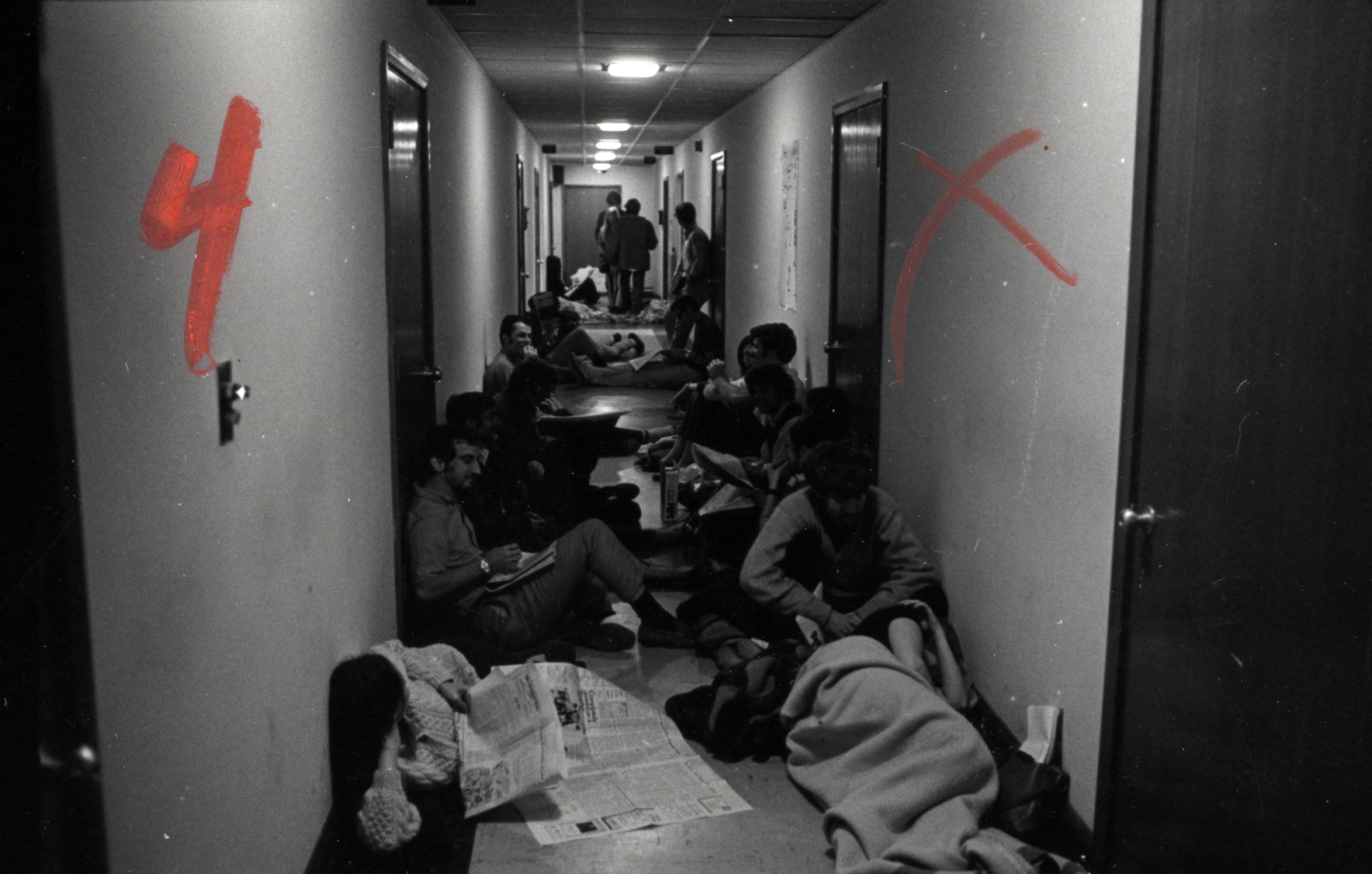

In 1969, the April Third Movement, created out of a broad coalition of campus organizations, occupied the Applied Electronics Laboratory (AEL), the site of classified (secret) military electronics research, for nine days. Fourteen hundred members of the Stanford community signed a statement of participation. But unlike sit-ins elsewhere, Stanford activists kept the building open, using it as a base from which to organize the campus. In the printshop we found in the basement, we printed newsletters, pamphlets and copies of support letters from dorms, departments and even the most conservative fraternities, using an estimated 750,000 sheets of paper we found on site. We held a faculty tea party, at which we discussed sit-in issues with skeptical professors, in the AEL courtyard. We celebrated a wedding, showed a movie, baked bread and wrote our own proposed guidelines for acceptable research at Stanford and SRI. With support from a campus majority, we forced the end to secret research on campus.

Fourteen hundred April Third Movement protesters occupied the Applied Electronics Laboratory building for nine days in April 1969, preventing classified war research.

In fall 1968, the Administration had established the SRI Study Committee in response to the demand by Students for a Democratic Society to halt SRI participation in the Southeast Asian war. SRI not only conducted electronics research; it had designed Vietnam’s oppressive Strategic Hamlets, a euphemism for the concentration camps in South Vietnam that were emplaced to separate the peasant “sea” from the guerilla “fish.” Little did the administrators and Trustees expect that the Committee would be releasing its report in the middle of the longest sit-in in a war-research building in world history. The April Third Movement had built majority support for the SDS demand that SRI be brought closer to the university so its research could be controlled.

In support of its SRI demand, the Movement occupied Encina Hall until police arrived, boycotted classes, and blockaded SRI’s counterinsurgency offices in the Stanford Industrial Park. After several hours, as hundreds of demonstrators were dispersed by police, protestors thrust rocks, a larger sewer pipe and at least two police tear-gas canisters into the building. We considered the protest a success, but Stanford still spun off SRI so it could continue its war research. Over 100 of us were arrested and convicted. Among the charges: disturbing the peace.

During the spring 1969 April Third Movement, the full faculty had voted to end credited Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) classes. However, the Administration and Trustees successfully pressured the faculty to reverse its position, so in January 1970 we formed the Off ROTC movement. We peacefully disrupted ROTC classes and prepared to throw water balloons at ROTC maneuvers. Activists were split between those who advocated “trashing” — the throwing of rocks to break windows at engineering labs, administration buildings and the Lou Henry Hoover building — and those who only supported non-violent sit-ins.

Hundreds of A3M activists blockaded SRI’s counterinsurgency offices in the Stanford Industrial Park on May 16, 1969, before being dispersed by police.

That tension was resolved at the end of April when off-campus police arrested civil disobedient protestors inside the Old Union just as the world was learning that the U.S. had invaded Cambodia. That unleashed the second most militant confrontation in Stanford Movement history. The Daily headlined, “Violent Fights Erupt After Sit-in; Students Battle Police For 4 Hours.” The following night was the most violent. After watching the play, “Alice in ROTC-Land,” thousands of demonstrators poured out of Frost Amphitheater to confront police. Incidentally, that performance launched the acting career of Sigourney Weaver, who played the title role.

Stanford students and faculty joined their counterparts at hundreds of U.S. campuses in the protracted Cambodia strike. New activists joined the established movement in reaching out to off-campus communities, while others blocked the entrances to ROTC and Encina Hall. The Administration canceled classes for the remainder of the year. And it “prosecuted” five of us for Contempt of Court for our anti-ROTC disruptions.

But our movement was not all writing and direct action. We used humor to build support. In late 1970, to raise money, I sold buttons that said “Go Reds—Smash State.” Football fans bought them as Jim Plunkett and the team prepared to face Ohio State in the Rose Bowl. Leftists bought them for their political entendre. In fall 1971, when Engineering Dean Joseph Pettit left Stanford to head Georgia Tech, I announced that I was running for Dean of Engineering. Of course — this was my point — the Deanship is not an elective office. Stanford never has been a democratic institution.

On April 3, 1970, Lenny Siegel “rudely and illegally” tried to call to order a meeting of the Academic Council in the Physics Lecture Tank.

As we opposed the war, we also worked for academic reform, fought for civil and gender rights and supported union organizing. But we also laid the groundwork for advocacy that I and many on campus continue to this day. Stanford has long provided desirable housing to faculty. It has gradually improved the housing opportunities that it provides graduate students. But it has never made much of an effort to create places for low- and middle-income employees to live. The official Moulton Committee reported this in 1969, so some of us formed Grass Roots to influence Stanford land use policies. However, the crescendo of anti-ROTC activity and the Cambodia Strike quickly eclipsed Grass Roots.

Still, I never abandoned my personal efforts to undo the massive Silicon Valley jobs-housing imbalance that Stanford originated. In 2014, I was elected to the Mountain View City Council on a platform that led to the construction of thousands of new housing units and plans for many thousands more. My advocacy came full circle in 2018 when, as Mayor of Mountain View, I joined other local municipal leaders in challenging Stanford’s unbalanced proposal for a General Use Permit from Santa Clara County.

I have recounted this history — not just the headlines but the hard work that created the campus majorities to challenge the trustees and administration — in my book, “DISTURBING THE WAR: The Inside Story of the Movement to Get Stanford University out of Southeast Asia—1965-1975.” The book and its associated website, http://a3mreunion.org, contain links to hundreds of Daily articles and original documents that I saved from my early years of activism.

Police guard the Old Union after expelling and arresting “Off ROTC” protesters as the campus and the World learned of the Cambodia Invasion, April 29, 1970.

The movement in which I participated changed Stanford forever, and we moved what became known as Silicon Valley away from its leading role in the military-industrial complex. And it led hundreds, maybe thousands of Stanford students into careers and avocations working for social, environmental and political change throughout the rest of our lives.

Lenny Siegel attended Stanford from the fall 1966 through March 1969, when he was kicked out. He served as Mayor of Mountain View in 2018.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to eic ‘at’ stanforddaily.com and op-ed submissions to opinions ‘at’ stanforddaily.com. Follow The Daily on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.