Those who remember are dying.

That is the urgent message that courses under the surface of the 20-minute Academy-Award nominated documentary short film “Colette.” The documentary follows the eponymous former member of the French Resistance, whose brother was killed at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp near Nordhausen, Germany. Colette, who evaded arrest during the war, never set foot in the camp herself, and the short film tracks Colette’s first visit to the site of her brother’s harrowing last days. Accompanying her on the journey is a young student historian, Lucie.

We meet Colette in her apartment in the north of France, where she presents as a proud, elegant woman. She gets that from her mother, who was a militant opponent to Nazism and set her daughter to work in the Resistance. During occupation, Colette crafted false documents, counted the cargo trucks that rumbled past her family’s window and helped amass weapons in caches. Colette emphasizes that there was no glamour in the Resistance — just sitting on a hard stone, notebook in hand, watching and waiting. In her living room, a portrait of her brother Jean-Pierre, taken secretly by her father while visiting him in prison, shows a defiant, confident young man.

Colette talks openly about how her brother was arrested and deported at 17. In her telling, the process of mourning seems rather complete. “The scar is still visible, but it doesn’t hurt. Or at least not as much,” she confesses. The film follows how the visit to the camp disturbs Colette’s feelings of closure, examining the difficult and — as the film seems to argue — endless process of mourning.

Lucie, the young history student in the film, works as a docent at the Mittelbau-Dora museum, preparing entries for what will be a biographical dictionary of the camp’s victims. Approximately 20,000 were murdered there over its 19 months in operation. Lucie decides to spend a week with Colette to complete Jean-Pierre’s entry, which is missing key aspects, including a photograph. Over the week, Lucie interviews Colette about her brother while they visit the camp. She appears thrilled to have a surviving relative of Jean-Pierre’s to interview and the opportunity to leave the archives for a bit.

On the train ride to Germany, Colette slowly unravels her recollections to the tune of Lucie’s curiosity. She brightens up when speaking about her brother, even though she confesses that they were never close. He was their parents’ clear favorite — she painfully recalls how her mother told her that Colette should have been the one to be imprisoned.

It is a story that Colette has told many times, but there is something in Lucie’s youthful probing and the interspersed shots of Colette pausing her recollections to gaze out the train’s window that suggest something is different this time. Indeed, as they approach the ruins of Mittelbau-Dora, Colette becomes visibly unsettled. On the evening of their arrival, the town’s mayor spots her in a restaurant and tries to give her a lengthy apology for his nation’s crimes. Colette snaps, demanding that everyone return to their tables and eat in silence.

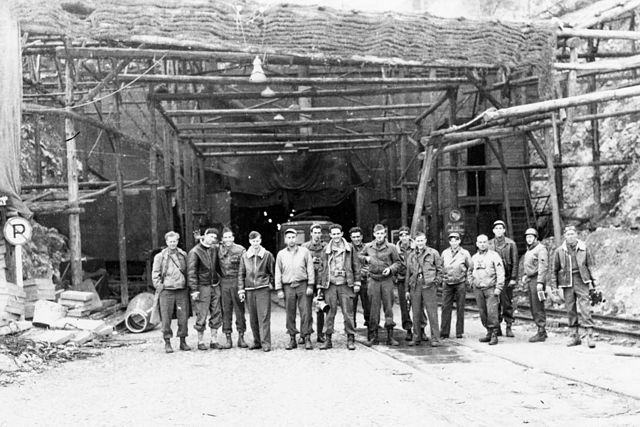

The film explores the never-ending practice of mourning — the way old wounds never fully heal, as Colette initially believed. When she walks through the block where her brother slept on the ground, her elegant composure erodes. Lucie wraps her arm around Colette’s, and the latter confesses, “I have made such an effort to forget.” After visiting the crematorium and the V-2 missile factory where Jean-Pierre was worked to death, Colette gives Lucie a ring with the initials J.P. — the only object she has left of her brother. “When you are a very old woman, you will say I was there when I was young,” she stutters through sobs.

Lucie is not the only prying figure. The camera is constantly capturing Lucie and Colette’s intimate moments, the complicated twists and turns of their emotional reactions to each other and to the atrocities that they are remembering together. Once they reach the camp, the camera’s curiosity verges on the unsettling, gawking at Colette as she cries. At the same time, its insistence on witnessing these excruciatingly intimate moments underlines a theme that runs through the movie — the need to face pain, to record the recollections of past crimes.

Through the pair’s conversations, the movie presents both hope and a warning. It reminds us that those who were very young during the war, the last witnesses of its horrors, will not be here for too much longer. At the same time, it underscores the power of an inspired youth to continue to tell those fading stories, to fervently remember the abominable.

The film closes with a reflection on the mysteries of memory, how the strife of antecedents is transmitted through generations. Colette asks Lucie to listen to the birdsong at Mittelbau-Dora, saying, “Who knows if birds are not a collection of our sorrows… maybe Jean-Pierre is telling us that he is happy.” Colette had never seen the value in returning to Germany, but her opinion on such “morbid” acts of remembrance changes throughout the film. At the start, she wondered why someone like Lucie would be determined to remember, to subject herself to living in the darkest regions of the past. Yet once she reaches Jean-Pierre’s block at the camp, she kicks herself for not bringing him flowers. It dawns on her that symbolic memorialization can fill the sense of powerlessness and alleviate ineffable pain.

By the end of the film, it seems that Colette has found some comfort in the knowledge that after she is gone, someone will still stop and listen to the birds tell their stories.

(The film is available for free streaming on The Guardian’s Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7uBf1gD6JY)