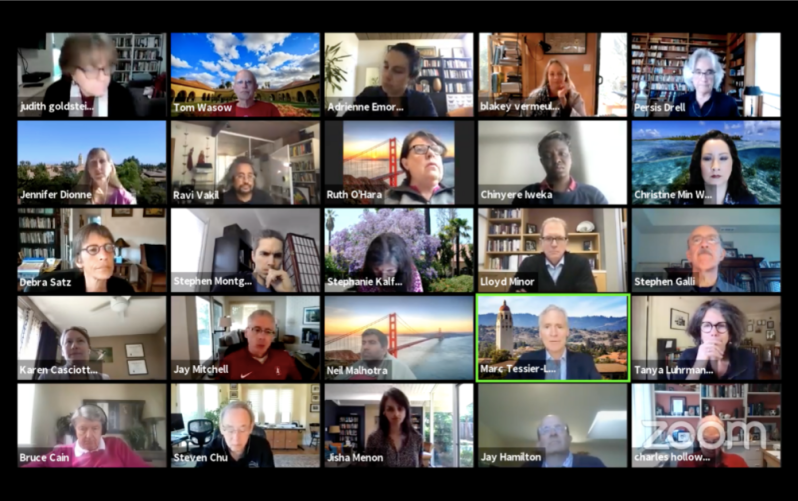

Faculty members spoke in favor of potential changes to the Stanford Honor Code, such as allowing teaching staff to proctor assessments and implementing a new tiered system for violations, at the Thursday Faculty Senate meeting. The proposed changes would reduce the burden on both faculty members and students, senators said.

Honor Code violations have increased annually and surged during the pandemic, according to Mark DiPerna, director of the Office of Community Standards. Nearly 300 honor code violations have already been recorded this academic year, in contrast to only 202 and 138 in the 2019-20 and 2018-19 academic years, respectively.

Last January, the Committee of 10 was impaneled to review and determine if the Student Judicial Charter, the Fundamental Standard and the Honor Code should be updated to foster a more efficient and fair process.

While the committee’s work remains ongoing, its initial findings suggest that the student disciplinary process is overly punitive and not educational. professor of medicine and Committee of 10 Chair Marcia Stefanick said that Stanford’s current “one size fits all” approach to student violations may not be consistent with the goal of the student disciplinary process, which is to “build character, not punish students.”

One solution the committee is studying is a code of conduct with varying levels of violations. This tiered system would adjust the student conduct process based on the level of the violation, requiring different burdens of proof and adjusting the length of time the violation stays on a student’s record.

The standard sanction for a first-time Honor Code violation is a one-quarter suspension and 40 hours of community service. Students who choose to resolve their case through the early resolution option are given a one-quarter suspension held in abeyance, according to the Student Conduct Penalty Code.

Computer science professor Mehran Sahami ’92 M.S. ’93 Ph.D. ’99 said that instructors may opt not to report some violations because they fear the consequences students could face given the uniform sanctions.

Stefanick added that the current process is too long with minor infractions taking months to resolve. The goal of the new charter, she said, would be to clear both violations expeditiously and restrict the period to submit a concern.

Many senators voiced support for the tiered system proposal and the lowering of sanctions for first-time violations. But the Honor Code’s stipulation that assessments cannot be proctored by instructors was met with the greatest calls for reform.

The Honor Code, written by students in 1921, articulates standards for both students and the faculty. While students are not permitted to give or receive unpermitted aid in course work, the faculty must also “manifest its confidence in the honor of its students by refraining from proctoring examinations.”

Mechanical engineering professor Juan Santiago said that allowing professors to proctor their own exams would allow them to address ambiguities in exam questions.

“Having the professor sit on a chair in the hallway 50 feet away and then having people come and ask the same questions until it happens enough times that I walk into the room … It’s a farce,” he said.

“It’s an absurd situation.” Santiago continued. “I go back to my little tiny desk by the bathroom so that they come ask me questions.”

Faculty Senate Chair Judith Goldstein echoed other senators and said that allowing professors to proctor exams will ease tension. Students will “feel that there is more equity in the room,” she said. “They don’t have to worry about other students copying off of them or cheating.”

Stefanick said that the Committee of 10 will continue its outreach efforts and compile recommendations throughout the spring quarter with the goal of submitting its report to the Board on Judicial Affairs, Associated Students of Stanford University, Faculty Senate and Office of the President during the summer quarter.

If approved, the recommended changes to the student conduct review processes will be piloted for a year starting in fall 2021.

Expanded principal investigator eligibility

A year after approving principal investigator (PI) eligibility for SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory staff and School of Medicine clinical educators, the Faculty Senate voted to further expand eligibility to staff who are part of shared facilities or service centers for a five-year trial period. M.D. and Ph.D.-level researchers and staff can now serve as PIs on projects in shared facilities or service centers.

Jennifer Dionne, a member of the Faculty Senate Committee on Research, said that shared facilities — which house critical research infrastructure — are an “an essential community” for researchers and educators. The electron and ion microscopy, nanofabrication and x-ray and surface analysis facilities are among the shared resources available to Stanford researchers. The transmission electron microscope, for instance, enabled researchers to discover the structure of the spike protein associated with COVID-19, Dionne said.

The change will allow the University to recruit and retain the most competitive staff, increase funding opportunities and expand the range of research opportunities for graduate students and postdocs at shared facilities, according to Dionne.