Stanford is a busy campus: It never sleeps, and people frantically move from place to place to join the next class, meeting or event. We have all heard about the infamous Stanford duck syndrome where everyone looks at ease on the surface, but underneath is fighting to stay afloat. We feel uncertain about whether or not we are doing enough with our time here when we see other Stanford students gracefully managing their responsibilities and forget we all are struggling under the societal pressures to be productive and build our futures.

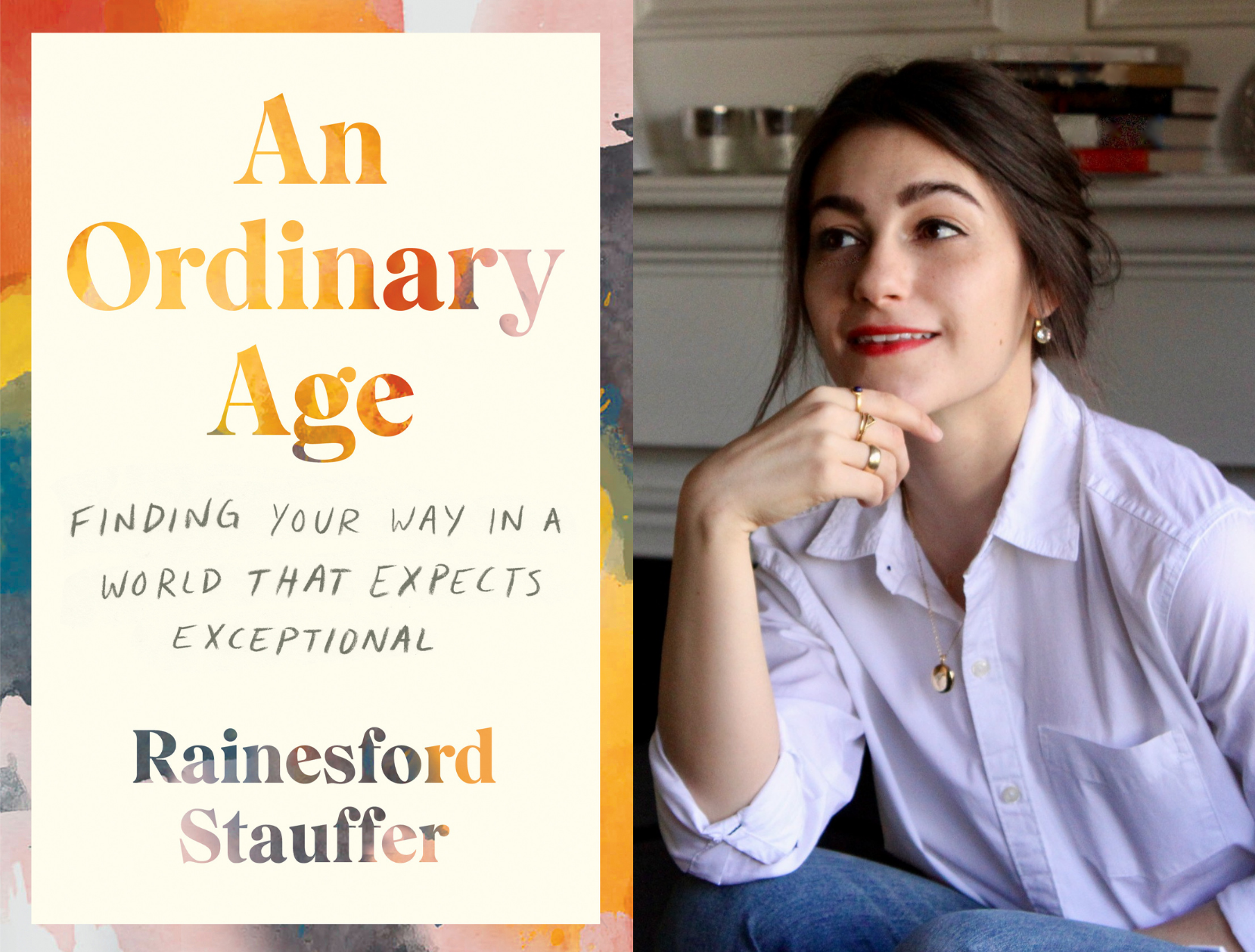

Rainesford Stauffer’s new book “An Ordinary Age,” out yesterday, is released during a particularly difficult time for young people like us. The global pandemic has disrupted important milestones and interactions in our lives, pushing us to seek refuge from the uncertainty of everything. Stauffer echoes our sentiments about the pandemic and reminds us that our circumstances are not normal; ordinary things like eating out at a cafe or going to class have, in fact, been extraordinary. Her book emphasizes people who are emerging into adulthood, which makes it especially relevant to young adults and college students like us.

Young adults face countless pressures to perform well and obtain opportunities and skills to build their own successful futures — and Stanford students are not immune to these pressures. We face stress and feelings of inadequacy in our pursuit of our goals. We become so caught up with work, school and other responsibilities that self-care seems like a waste of time or another thing needed to be fit into an already packed schedule. My own dorm incorporated self-care practices during meetings and on-calls, and plastered self-care suggestions in the hallways and main entrance. Despite all these calls for self-care, I felt Stanford students viewed self-care as another task to add to their busy day and wondered how they could possibly balance all the stressors and demands — because I, myself, felt guilty for not keeping up and for struggling to balance all the responsibilities in my own life.

In “An Ordinary Age,” Stauffer writes all about these pressures: from competing with others for internships to self-care’s intertwinement with a capitalist’s meritocratic mindset. Stauffer wonders when “‘average’ became a bad word, synonymous with ‘failing’ instead of just ‘fine.’” She describes how self-care — and how it manifests in something like cultivating hobbies — may feel unproductive to us and even unattainable with other socioeconomic barriers and scheduling conflicts. Self-care, she states, is another “gimmick to remind us that really whatever we are feeling is all our fault anyway, and we should be able to fix whatever it is without assistance or support.” It is not our fault we feel guilty or stressed about self-care. She reassures us that self-care does not have to be extravagant — it can just be existing and doing nothing during that time. While the book does not offer concrete advice and tips to create a routine, step-by-step self-care practice, it does remind us that what we are doing is enough.

“An Ordinary Age” also touches on facets of work, love and dating, college, hobbies, religious affiliations and friends. Each of these chapters are not only a reflection of Stauffer’s own experiences, but also the experiences of other young adults in different situations from her own. Stauffer discloses a discretionary statement that while her book may not capture all the experiences of young adults, she offers a small sampling of young adults’ experiences in these pages who are trying to build their futures and navigate the pressures of young adulthood.

Within these personal stories and pieces of advice, Stauffer’s main idea is that we should try to find the extraordinary in the ordinary. Like we are always told: It is the little things that count. Sounds simple and kind of obvious. But quite frankly, society forgets this all the time, moves on too quickly and is too busy. Stauffer’s hope, as stated in an article in Teen Vogue, is not to “capture every lived experience,” but instead that “the narratives shared in it remind us that we aren’t in it alone, and reminds you that you’re good enough — right now, as is. Not your best self, not your future self: Your ordinary self, right now.”

This conversational approach to the book provides an opportunity for readers to reflect alongside Stauffer herself, through any sentences they relate to, and opens up a path to enter into conversation with her and the young adults featured in the book. I found myself highlighting most of Stauffer’s points and appreciated how she ended all her chapters with a concise sentence that captured the essence of the chapter. These quotes can definitely be written on sticky notes or someplace where you can go back to for inspiration and support whenever you feel stressed or uncertain.

Reading through “An Ordinary Age,” each page felt familiar to my own concerns and resonated with me in terms of my college experience and as a young adult who will be entering her 20s. I’m sure the rest of the Stanford community will resonate with and find relevant takeaways from the book that will help us during the time we are supposed to have the best four years of our lives, but which has become increasingly difficult and stressful to pursue amidst a pandemic.