Field hockey’s loss to top-ranked UNC in the quarterfinals of the NCAA Tournament is supposed to be the last game for the program at the varsity level — the last for a 118-year-old program that has been on The Farm nearly as long as the term “The Farm” itself has been in use.

Stanford’s decision to discontinue the program and the initial response to that decision have been well-documented. Now, nearly a year after the announcement, past and present members of the team continue to push for the reinstatement of their sport on and off the field.

This year’s team, for example, crossed out “Stanford” on their uniforms with black tape throughout the season and playoff run in protest of Stanford.

Off the field, previous generations of the program have formed Save Stanford Field Hockey, an organization made up of alums and supporters of the sport. After the initial outrage over the decision, members of the group began channeling their anger into action right from the beginning.

Elise Ogle ’14 MA ’15 and Linda de los Reyes ’84, who knew each other from post-collegiate club field hockey, quickly got in contact and helped form the foundation of the organization with other alums of the program. They worked to disseminate information to the more than 400 field hockey alums, while continuing to reach out and expand their pool of connections.

One such alum, Kathy Levinson ’77, was working with the university last year to create an endowment to honor the memory of a former teammate. She continued to reach out to potential donors right up until she found out on July 8 the sport would be discontinued, the same day as everyone else. She — like so many others — was taken aback by the abruptness of the announcement.

“I’ve been a longtime significant donor to Stanford field hockey and wasn’t given any advanced notice, or any indication that this was in the works,” she said. “Why would you allow me to continue to reach out to potential donors to create this endowment if you [the university] were going to cut the sport?”

Soon after, Levinson reached out to Nathalie Weiss ’16 and Alexander Massialas ’16, who are former members of the men’s rowing and men’s fencing teams, respectively. The trio created the “Stanford Athletic Response Team.” She, along with friend and women’s basketball alum Jennifer Azzi ’90, also realized the importance in expanding to include the other existing 25 sports, which led to 36 Sports Strong, a collection of alums and supporters of all 36 Stanford varsity sports.

“Kathy was one of the creators of the 36 Sports Strong group,” Ogle said. “And has really spearheaded a lot of their efforts to unite all of the teams.”

Ogle called her and her work for both 36 Sports Strong and Save Stanford Field Hockey, “just incredible.”

“I think one of the most wonderful things that has come out of this terrible decision is that … we’ve reconnected with all our alums in a way that we hadn’t been many years,” Levinson said.

“It’s really wonderful to see this multi-generational, multi-race, multi-sport group come together on behalf of an institution that we all love,” she continued. “We want to help right that wrong and help Stanford regain its moral compass … because we have such an affinity for our school. If we didn’t care about the school, I don’t think this ever would have happened.”

When asked about the ongoing response to the university decision, Stanford Athletics spokesperson Brian Risso wrote that Athletics has been “supportive” of the current team’s decision to cross out Stanford on their uniforms. He also pointed back to the rationale laid out in the initial announcement last summer, which named “financial sustainability and competitive excellence” as driving forces.

Regarding the former, 36 Sports Strong has presented the University’s Board of Trustees with a proposal to self-fund not just the 11 discontinued sports, but also all non-revenue generating ones.

Of the latter, “the culture of Stanford is really much more broad based, attracting elite athletes from all walks of life,” Levinson said. “It’s evidenced by the number of Olympians that we’ve created. Just go into the, you know, the Hall of Champions.”

This year alone, wrestling’s Shane Griffith and synchronized swimming each won national championships. Field hockey won the America East conference for a fourth time in the past five years.

On Wednesday, members from eight of the 11 sports — including an individual on the field hockey team — filed lawsuits challenging the University’s decision to cut the programs.

Ogle acknowledged that reinstatement would not necessarily solve broader issues within field hockey, but said that cutting the sport would be even more detrimental.

“There’s definitely areas of improvement for diversity and accessibility for field hockey as a sport,” she said. “But there’s so much more to that. And a lot of it takes time; it goes way beyond money. It takes dedicated people who understand the importance and want to build it. And those people are coming from Stanford.”

“It’s why I work three coaching jobs outside of my full-time job,” Ogle said. “It’s because I love it and I feel like I am really driven to give that opportunity to others so that there can be more people like me.”

Without Stanford field hockey leading the way, de los Reyes does not know what will happen to the sport throughout the West Coast. On a more personal level, it was her daughter’s dream to play for the Cardinal.

The impact will also ripple beyond the confines of the field.

“It’s another sport for girls that you, just take it away and it’s just sad,” she said. “It’s a big hole in developing girls, and we’ve talked about many times how playing sports helps develop leaders and teammates and camaraderie.”

If Stanford were to reinstate the sport, Ogle, Levinson, de los Reyes and others are the ones who will continue to help expand and grow the sport that, in many ways, defined their experiences at Stanford and beyond.

Until then, alums and supporters have formed “a little army to fight the decision,” as Ogle put it.

“It’s been a roller coaster,” Ogle continued. “On top of a lot of other things happening this year, you kind of question ‘Am I making the right decision in fighting for this?’ and it takes a lot of reflection for me, reflecting on my own story, or reflecting on stories of my teammates, gives me that level of understanding.”

“I wouldn’t be where I am today”

Elise Ogle (Photo courtesy of Elise Ogle and Save Stanford Field Hockey)

Trigger Warning: This section of the story contains mentions of suicide that may be troubling to some readers.

When Elise Ogle ’14 M.A. ’15 was younger, her father — a high school teacher and football and wrestling coach — would take her and her brother to summer practices for the teams. There she was first introduced to the sport of field hockey. Though she had no prior experience, the school’s coaches began inviting her to practice, and soon she was a member of their club team.

Ogle, who is biracial and was adopted at a young age, at times struggled to find her identity within field hockey, but her coaches cared deeply about accessibility and took time to ensure that she felt a part of the team on and off the field.

“I never saw myself really reflected in the players of my sport, and field hockey is predominantly white,” she said. “There’s a lot of issues with field hockey and access to it, but I was given an opportunity through my high school coaches, who really went out of their way to welcome people into the sport… And that opportunity has changed my life.”

Her high school coaches took extra time to work with her and provided equipment and encouragement. During this time, Ogle set her sights on Stanford and began meeting with university’s coaches and attending summer tournaments and camps. Academically, she ensured her course load was rigorous and met the lofty standards for acceptance to the university, with help from her father and coaches.

Then, as Ogle put it, “the rest is history.”

She was accepted into Stanford and was a Cardinal from 2010 – 2015. Over the course of the four years — she redshirted the 2011 season — Ogle played in 64 games, scoring five goals and collecting 17 assists. She also began working in the Virtual Human Interaction Lab within the Department of Communication and took classes in a variety of subjects.

Elise running and looking across the field during a game (Photo courtesy of Elise Ogle and Save Stanford Field Hockey)

“But when I look back on my personal journey, I feel kind of sad about it,” Ogle said. “I felt like it was really hard as a student to really connect with people on a deeper level. And I felt like the status quo was just to pretend everything was okay.”

During Ogle’s sophomore year, her close friend and roommate died by suicide. She said she felt “broken” following the passing, but field hockey was there for her.

“Piece by piece, the support from my Stanford hockey family put me back together,” she wrote in a statement. “Over time, I started finding joy again. They sparked a light within me that had been missing for a long time.”

Reflecting back, it was these moments and gestures from her teammates and coaches that helped her find herself when she was at her lowest.

“I needed to remember that myself, my health, my happiness was more important than anything, was more important than grief, performance, all these things that, leading up to getting to Stanford, are the most important things that you can have, that can get you in,” she said. “I needed to kind of let go of those things and really get back to focusing on what really mattered.”

“They told me that the only thing that mattered was my health and my happiness,” she said of her teammates and coaches. “And that was something that no one had ever told me before.”

Ogle is currently working to expand the accessibility to and the treatment of young adult and adolescent mental health through digital therapeutics with a small startup company, Limbix. She coaches youth field hockey on the side.

“I’m writing content to help motivate teens, to be, to feel like their best and healthiest selves,” she said. “And I learned the importance of that, through my experience at Stanford, through specifically being a part of a team.”

“I wouldn’t be where I am today without this program,” she said.

“Fighting tooth and nails for everything”

Kathy Levinson (Photo courtesy of Elise Ogle and Save Stanford Field Hockey)

Kathy Levinson ’77, Stanford’s only three-sport varsity athlete, has likely donned a Cardinal uniform more often than any other athlete in school history. She was on the field hockey, basketball and tennis teams during her four years at Stanford, and would have played more sports if she could have.

“Now it’d be harder I think to play three sports because of their off seasons and training, but I just really looked forward to going from one season to the next,” she said. “I would have played more sports if they were spread out more. I could have played more, but three is the most you could have done. So that’s what I did.”

Despite her love for basketball and tennis, the sport of field hockey was a unique experience for her.

“I really liked the camaraderie on the field hockey field,” Levinson said. “There’s a way in which you’re far apart from people on the field and yet, you can’t really be a solo contributor.”

She didn’t begin playing the sport until she was 14, however, when she moved to the East Coast from the Midwest. From there, Levinson worked her way into Stanford, where she described her athletic experience as her “saving grace,” despite playing in the early days of Title IX and without any scholarship opportunity.

At the time, Levinson said, field hockey was very much defined by the team around her, as the university did not prioritize the sport.

“We had a coach that had never played field hockey, didn’t really like field hockey and certainly had never coached field hockey,” Levinson said. “So we had to come together to benefit ourselves because clearly the university wasn’t really paying much attention to it or wasn’t that interested in it.”

“We really had to push hard for everything. For uniforms, for balls, the field that we played on was outside of Roble [Hall] had tall grass and was not well-kept. And so we found ourselves fighting tooth and nail for everything,” she continued.

Likening her experiences to what this year’s field hockey team endured, Levinson’s team excelled, making it to the national tournament each of her final two years at Stanford — the first two years there was a national tournament for women.

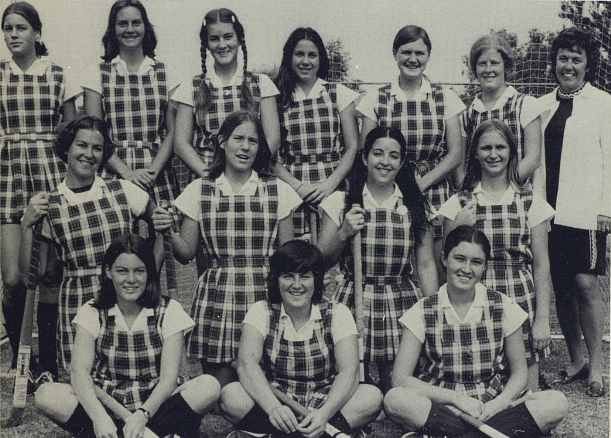

A field hockey team picture from the 1974-75 yearbook (Photo courtesy of Elise Ogle and Save Stanford Field Hockey)

“We had to work together for everything that we got because nothing was given to us,” Levinson said. “We really had to stand together, speak together, protest together, demand together to get what we considered equal treatment. And so I think there was something about being in the foxhole together, which brought us even closer together, not only as teammates but as human beings.”

“An injection of love of the sport”

Linda de los Reyes (Photo courtesy of Elise Ogle and Save Stanford Field Hockey)

Over time, field hockey has become a part of the identity of Linda de los Reyes ’84.

It didn’t begin that way. Originally drawn to softball in high school because her friends were on the team, she quickly realized that the sport wasn’t for her. It was walking back from the softball tryouts, however, where she first saw field hockey being played.

“It looked interesting — kids were running around with sticks,” she said. “So that was my first introduction. And from the moment I picked up the stick, it was just, I didn’t want to put it down.”

The sport helped her find a place at Stanford once she arrived, as there were 10 other freshmen in her recruiting class. It was these people and teammates who make up many of the people she’s still friends with today.

Photo courtesy of Linda de los Reyes and Save Stanford Field Hockey

“When you wake up, you go to school, and then you go to field hockey practice,” de los Reyes said. “So yeah, it was hard to really separate that from your identity. And it was great.”

The experience not only left an impact on her, but, more recently, also her daughters. She coaches in Northern California at the middle school, high school and club levels and introduced her two daughters to the sport from a young age.

De los Reyes coaching one of her field hockey teams (Photo courtesy of Elise Ogle and Save Stanford Field Hockey)

She described Stanford as a beacon for field hockey in Northern California.

Some of the biggest tournaments in the area at the club level every year are the ones hosted by the university, attracting numerous youth club teams in the surrounding area.

“It’s kind of one of the big ones that everybody kind of works toward and practices and trains for and they put their best teams out there,” de los Reyes said. “It’s just this level of competition and camaraderie the same time when you bring all the clubs together like that. Stanford has provided that.”

Field hockey head coach Tara Danielson and assistant coaches Patrick Cota and Steve Danielson also host summer day camps, which both of de los Reyes’ daughters attended.

“The Stanford coaches are fabulous,” she said. “They have so much to share. And they do it in such a way that makes it fun and motivating for the kids.”

And beyond the play on the field itself, de los Reyes instructs her players to go watch Stanford field hockey in action since their home games are so close.

“[The games] are so thrilling and exhilarating and motivating,” she said. “My own daughters come back from one of those games going, ‘I want to go out and play.’ So we come home, they grab their sticks, and they just start hitting around the ball again. That’s so fun to see, it’s like an injection of love of the sport again.”